Modern day slavery is on the rise. In the 2014 UN Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (just published at this link) we read about the following tragic trends:

- “Between 2010 and 2012 victims from at least 153 countries were detected in 124 countries worldwide”

- In the first report (2012) one out of four trafficked persons was a child; now in places like the Middle East and Africa it’s two out of three

- 70% of all the victims are female, and two out of three children trafficked are girls

- More than 6 in 10 victims were transported across at least one national border

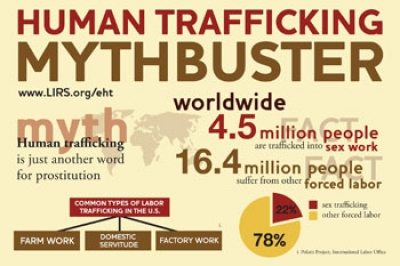

- In a New York Times article about this report we read that … “While sexual exploitation remains the predominant reason for trafficking, victims are also increasingly used for forced labor”

- Organized crime syndicates operate with near impunity because many countries do not enforce the laws they have passed on this issue; in 40 percent of countries there have been few or no criminal convictions

- The opening sentence: “The exploitation of one human being by another is the basest crime. And yet, trafficking in persons remains all too common, with all too few consequences for the perpetrators.”

Sexual exploitation of children, I hope we can all agree, is the vilest form of cruelty to our fellow human beings. And as the report lays out in great detail, no part of the world is spared from this plague and women bear the brunt of this tragedy. I touched on some of this in a series of three blogs in 2012 under the title of “Religion and Patriarchy” in the category of “religion and human rights.” But so much more should be said, especially when you realize that every year over 12 million persons, with more and more of them now being children, are abducted and enslaved.

Note too that the percentage of trafficked persons used for forced labor is on the increase. We know, at least anecdotally, that many children are sold by parents who are too poor to care for their many children, and girls in particular. We also hear about young women hiring themselves out as maids to wealthier families in other parts of the world and being badly exploited in slave-like conditions. It could be in the United States or Europe, but even more likely in countries like in the Arabian Gulf area where laws and their enforcement are particularly lax. Here’s an article about Indonesian maids being treated as “modern day slaves” in Hong Kong.

All this to say that the International Organization for Migration (IOM) figure of 21 million is very likely just the tip of the global trafficking iceberg. In the official statement announcing the release of the Report on Trafficking of Persons, Yury Fedotov, the executive director of the UN Office of Drugs and Crime, wanted to emphasize that the statistics told only part of the story. “It is clear that the scale of modern-day slavery is far worse,” he wrote.

We're talking about the poorest of the poor here – those robbed of their basic human rights, stripped of all dignity and at the total mercy of their captors. But not far behind are the more than ten million internally displaced persons (IDPs) who are now under the care of the UN Refugee agency (UNHCR). They have become IDPs through war and natural disasters. But just as many more people are being trafficked than simply those who can be counted, there are many more people suffering from famine and war than those directly managed by the UNHCR.

That there is often a direct link between the trafficking of persons and poverty is a point made by a respected NGO specialized in this work, the Institute for Trafficked, Exploited & Missing Persons (ITEMP). They point to the 2009 US State Department Trafficking in Human Persons report. Here is how a short article on their homepage frames the issue:

"By comparing gross domestic product information with source/destination information provided in the State Department’s 2009 Trafficking in Persons report, ITEMP personnel discovered a strong correlation between a country’s per capita GDP and their odds of being a source or destination country for international human trafficking.

Every $1000 increase in a country’s GDP makes the country nearly 10 percent more likely to be a destination for international human trafficking victims.

Likewise, every reduction of $1000 in a country’s GDP makes the country 12 percent more likely to be a source for international human trafficking victims.

‘By finding the roots of the problem, we can begin to look for permanent solutions,’ ITEMP Director of Operations Charles Moore said."

In the first blog we used stories and figures from the IOM to look at one aspect of that growing gap between rich and poor globally. We saw that the estimated 800,000 migrants who yearly entrust their escape from either crushing poverty or political instability to unscrupulous smugglers are only a small part of the total picture.

We discovered that, despite the spike in violence and political unrest in the Middle East, most migrants are motivated by the desire to provide financially for their families. Poverty is at the root of these mass migrations today.

And what is more, beyond the millions of refugees and persons trafficked, we learned that 21 percent of the world’s population lives in “extreme poverty” (living on less than $1.25 a day). That’s roughly 1.4 billion of our fellow human beings.

Poverty and the unequal distribution of resources – including basic necessities like food and shelter, but also access to safe water, good schools, electricity, health care, and more – is actually worsening in some of the developing countries (including the US), says the World Bank in a short “Poverty Overview.”

Lessons from growing inequality in the US

So the issues of modern-day slavery, the plight of the refugees and the “extreme poor” remind us that we live in a world plagued by inequality. But as an American citizen, I am also reminded of the fact that at home too the gap between haves and have-nots has grown wider in the last few decades.

Google’s chief economist Hal Varian teamed up with the New York Times' Upshot on a research project in the summer of 2014 seeking to correlate particular searches on the web with the easiest and the toughest places to live in the US. This was based on previous research that had demarcated these areas on the basis of six factors including life expectancy, education and income.

David Leonhardt explains that searches with the highest correlation to the poorest US counties (mostly in Kentucky, Arkansas, Maine, New Mexico and Oregon) covered the following interests and concerns:

“. . . health problems, weight-loss diets, guns, video games and religion are all common seach topics. The dark side of religion is of special interest: Antichrist has the second-highest correlation with the hardest places, and searches containing ‘hell’ and ‘rapture’ also make the top 10.”

By contrast, “In the easiest places to live, the Canon Elph and other digital cameras dominate the top of the correlation list. Apparently, people in places where life seems good, including Nebraska, Iowa, Wyoming and much of the large metropolitan areas of the Northeast and West Coast, want to record their lives in images.”

For Leonhardt this project shows that “[t]he rise of inequality over the last four decades has created two very different Americas, and life is a lot harder in one of them.” He explains,

“Income has stagnated in working-class communities, which helps explain why ‘selling avon’ and ‘social security checks’ correlate with the hardest places from our index. Inequality in health and life expectancy has grown over the same time. And searches on diabetes, lupus, blood pressure, 1,500-calorie diets and ‘ssi disability’ – a reference to the federal benefits program for workers with health problems – also make the list. Guns, meanwhile, are in part a cultural preference, but they are also a health risk.”

George Packer, a staff writer at the New Yorker, delivered the 2011 Joanna Jackson Goldman Memorial Lecture on American Civilization and Government at the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars & Writers. It was entitled, “Inequality and Social Decline in America” (later published in Foreign Affairs Magazine). The nub of the issue is this, he writes:

“The persistence of this trend toward greater inequality over the past 30 years suggests a kind of feedback loop that cannot be broken by the usual political means. The more wealth accumulates in a few hands at the top, the more influence and favor the well-connected rich acquire, which makes it easier for them and their political allies to cast off restraint without paying a social price. That, in turn, frees them up to amass more money, until cause and effect become impossible to distinguish.”

Growing inequality, the result of this trend, “leaves the rich with so much money that they can binge on speculation, and leaves the middle class without enough money to buy the things they think they deserve, which leads them to borrow and go into debt." This was certainly one of the causes of the 2008 Great Recession and it “hardens society into a class system, imprisoning people in the circumstances of their birth – a rebuke to the very idea of the American dream.”

Two years later, President Obama put it in terms of upward mobility, or in this case, the lack thereof:

“The problem is that alongside increased inequality, we’ve seen diminished levels of upward mobility in recent years. A child born in the top 20 percent has about a 2-in-3 chance of staying at or near the top. A child born into the bottom 20 percent has a less than 1-in-20 shot at making it to the top. He’s 10 times likelier to stay where he is. In fact, statistics show not only that our levels of income inequality rank near countries like Jamaica and Argentina, but that it is harder today for a child born here in America to improve her station in life than it is for children in most of our wealthy allies – countries like Canada or Germany or France. They have greater mobility than we do, not less.”

This issue of inequality has loomed so large in our political and social discourse that the New York Times ran a series on the topic for a year and a half. It was moderated by Nobel-Prize in economics laureate Joseph Stiglitz (2001), who, in the closing article of the series (“Inequality Is Not Inevitable”) called the United States “the advanced country with the greatest level of inequality.”

I will come back to him, but first some figures from a study that was published this month. Henry Gass describes the project: “The study, from Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley and Gabriel Zucman of the London School of Economics, uses a greater variety of sources to paint its picture of wealth inequality in the US than other recent analyses.” Here are some highlights:

- Although US economic growth is “positive and steady,” it doesn’t benefit everyone equally, as “America’s overall wealth is being concentrated in fewer and fewer hands”

- “the richest 0.1 percent of Americans [“160,700 families with net assets above $20 million”] have as much of the country's wealth as the poorest 90 percent”

- “While the bottom 90 percent of Americans and the top 0.1 percent control about 22 percent of the country's wealth each, the top 0.01 percent of Americans [“16,000 families with a net worth of $371 million”] now control 11.2 percent of total wealth.” You have to go back to 1916 to find similar figures in the US

- Though both have risen steadily over the past 40 years, “income inequality is less extreme than wealth inequality” and “wealth is ten times more concentrated than income today”

- 1986 is the date when the average wealth of 90% of Americans began to stagnate and when the richest Americans’ wealth began to increase; the trend, so far, has shown no signs of abetting, and it is unique to the United States

- Recently the proportion of wealth that the super-rich hold in bonds has increased in proportion to the wealth they hold in stocks – “meaning that an increasing portion of America's wealth could be inherited rather than built through business”

Back to Stiglitz. C.E.O.s make on average 295 times more than the typical worker, he says. This is an “ersatz capitalism”: our response to the Great Recession that struck late in 2007 was to “socialize losses and privatize gains.” That is, tax payers paid the bills, while the super wealthy pocketed millions more. No one was indicted and much less imprisoned for years of shady gambling on national wealth (my take on it). But this is no inevitable trend, he argues:

“If it is not the inexorable laws of economics that have led to America’s great divide, what is it? The straightforward answer: our policies and our politics. People get tired of hearing about Scandinavian success stories, but the fact of the matter is that Sweden, Finland and Norway have all succeeded in having about as much or faster growth in per capita incomes than the United States and with far greater equality.”

What is more, Stiglitz isn’t shy about laying bare the causes and manifestations of this rising inequality. In part he blames the bankers and corporate heads who in their passionate push for laissez-faire economics (less regulation, please!) nevertheless have welcomed the series of bail-outs that have characterized the era inaugurated by Reagan and Thatcher. Moreover, this economic privilege is undergirded by political privilege. In other words, “The American political system is overrun by money. Economic inequality translates into political inequality, and political inequality yields increasing economic inequality.” As a result, almost a quarter of children under five in America are poor.

Poverty and political powerlessness also correlate with a restricted access to justice. Reeling as we are with the fallout of a black eighteen-year-old gunned down by a white policeman in Ferguson, MI, we know that our justice system as a whole is broken. As Stiglitz puts it, the contrast between the two Americas couldn’t be greater:

“Where justice is concerned, there is also a yawning divide. In the eyes of the rest of the world and a significant part of its own population, mass incarceration has come to define America — a country, it bears repeating, with about 5 percent of the world’s population but around a fourth of the world’s prisoners.

Justice has become a commodity, affordable to only a few. While Wall Street executives used their high-retainer lawyers to ensure that their ranks were not held accountable for the misdeeds that the crisis in 2008 so graphically revealed, the banks abused our legal system to foreclose on mortgages and evict people, some of whom did not even owe money.”

Theology does matter

In the first blog I wrote that inequality worldwide was a human rights issue, thus both moral and theological. If God created us all – each and everyone of us – in his image, calling us to be his representatives on earth, his khulafa’ or trustees over his creation, we should not tolerate the fact that millions of us are trafficked for sex or greed, or struggling to find food to feed their families, or forced out of their land by wars and then drowned in the sea by greedy smugglers or left to die of thirst under the scorching Texas sun.

According to the Qur’an,

“We ordained for the Children of Israel that if anyone killed a person not in retaliation of murder, or (and) to spread mischief in the land - it would be as if he killed all mankind, and if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all mankind” (Q. 5:32)

This verse closely parallels some discussions in the Talmud, as I showed in one of my earliest blogs, “‘My Brother’s Keeper’ as Human Solidarity.” In the same vein, but more along the lines of poverty, we read in Deuteronomy, “Cursed be anyone who deprives the alien, the orphan, and the widow of justice” (Deut. 27:19 NRSV). Then this from Isaiah the prophet, “Learn to do good. Seek justice. Help the oppressed. Defend the cause of orphans. Fight the right of widows” (Is. 1:17 NLT).

Inequality to some extent is natural. Each human being is born with abilities and disabilities, and within a specific family, class and cultural context. Yet the kind of inequality we have been examining in these two blogs is egregious and an insult to the Creator.

There is a lot people of faith can do – yes, and people of compassion and human decency of all stripes – both locally and globally to reduce inequalities and contribute to human flourishing among those suffering the most. It involves both charitable ventures and political advocacy. In fact, instead of rivalries, misunderstandings, and polemics between religious traditions, let’s compete in good works; and better yet, let’s link arms, pool our strengths and get to work.

“Each community has its own direction to which it turns: race to do good deeds and wherever you are, God will bring you together. God has power to do everything” (Qur’an 2:148, Abdel Haleem translation).