-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

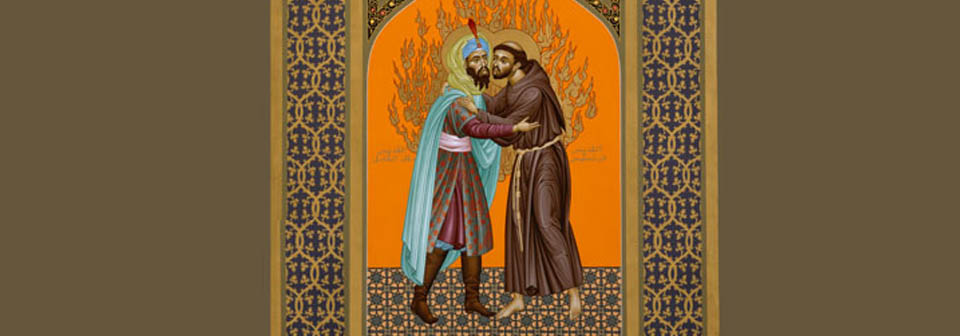

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

Pakistani American academic, Ahmed Afzaal, an associate professor of religion at Concordia College in Minnesota, departed from his research and writing on religion when he published Teaching at Twilight: The Meaning of Education in the Age of Collapse (Cascade Books, 2023).

Our paths intersected, Afzaal and I, when in 2012 I co-edited an issue of the journal Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture and Ecology on Islam and Ecology. We accepted and edited Afzaal’s contribution on the “Disenchantment of the Environmental Crisis” (see my own article on Shari’a and Ecology).

I completely identify with Afzaal’s choice to write this book. The environmental crisis keeps worsening, and in spite of the world’s scientists’ dire warnings, it seems that the governments of nations that are most responsible for the catastrophic acceleration of global warming are the ones most dragging their feet. In fact, the president of the one nation most responsible for the present crisis denies there is any crisis at all and has doubled down on the use of fossil fuels while sidelining clean energy production! I myself have posted a good deal on environmental topics.

As the title of his work indicates, Afzaal is issuing two related calls to his main audience, fellow university professors, and by implication, to all educators. The first is to have them reflect on the purpose of education itself. His answer to that question is simple. If love is the greatest value—which he believes it is, then education’s raison d’être is “to promote the welfare and well-being of the younger generation” (p. 74). This is not happening at the present, he avers. Why not? And this is the second message: because curricula have stayed the same for decades and decades, and they make no mention of the dystopian future awaiting these students. In a nutshell, the world’s twin crises of runaway capitalist economic growth and the resulting catastrophic destruction of our planet’s climate and biodiversity are quickly moving human civilization as we know it toward its impending collapse. Yet our educational institutions make little or no mention of it.

This is indeed a bold and jolting double message Afzaal aims to pass on to his fellow educators. But Teaching at Twilight’s emphasis is less about the collapse itself (and even less about potential solutions) and more on the crucially salutary role teachers could play in the lives of today’s students. Let me then rephrase the two messages: 1) the present trajectory of the global economy gravely threatens the planet’s carrying capacity, and so we are headed toward a collapse of the entire system resulting in untold human suffering; 2) not equipping the younger generation for this future is irresponsible and ethically reprehensible. Yet how can we prepare students for the world they will soon be experiencing? If we do our job well, ponders Afzaal, we could potentially transform that inevitable crash into a softer landing.

We’re now in overshoot and the Collapse is inevitable

Afzaal is right: the research is definitive and the literature is abundant: the global economy can only stay afloat if it keeps growing as it has up to now, and yet it is already consuming the Earth’s finite resources, unraveling its climate and generating so much waste that we have already overshot (we’re in “overshoot”) the Earth’s biocapacity. Ice is melting at exponential rates from both polar caps, causing sea levels to rise several feet in the next decades and forcing whole cities to migrate; superstorms will grow more frequent and ever more intense, as will droughts, floods and fires, and the number of climate change refugees will rise to several hundred million, wreaking havoc on poorer and richer countries alike.

And if that were not destabilizing enough, consider the quandary of our global capitalist economy. Its modus operandi goes back to the industrial revolution of the 18th century. See Afzaal’s definition of this “Business-As-Usual” in operation: “industrial capitalism with continuous economic growth, coupled with a culture and a lifestyle whose prime directive is ever-increasing consumption” (p. 20). This has two implications, he argues:

“First, while both capitalism and industrialism can exist independently of each other, it’s really the synergy of capital and technology that has brought the modern world into existence. Second, I mentioned ‘economic growth’ separately just for emphasis; in reality, the imperative to constantly expand the economy is already built into the logic of capitalism. The same applies to consumerism, which is absolutely necessary for maintaining the economic growth without which capitalism is inconceivable” (p. 20-1).

So we must all come clean on this: through our own daily activities and choices, we maintain and support this Business-As-Usual system. And the higher our income and the more lavish our life-style, the more we contribute to the degradation and destruction of the biosphere that makes our human life possible in the first place. That is our current “Predicament,” warns Afzaal. And it’s speeding up the advent of a new “Great Depression,” and this time in tandem with apocalyptic climate effects.

If reading this is causing your blood pressure to rise and increasing your anxiety, you are not alone. And we’re not likely to derive any comfort from sentences like, “All past civilizations have collapsed, and so will our current global civilization” (p. 222). Afzaal is very aware of this, and he has peppered throughout his book little boxes on the page that tell the reader to stop and reflect; also, to get up, walk around to relax their muscles, and then jot down their thoughts and feelings in a notebook. Another helpful feature for readers is his bulleted summary of 3 to 5 main points at the end of each chapter. What’s more, his chapters are short and very readable.

Right brain, left brain

According to common parlance, engineers operate out of their left brain, while artists do so out their right brain. More recent brain research has shown that, actually, “both hemispheres are involved in everything that the brain does” (pp. 98-9). Thus, any function carried out by the brain is carried out by both hemispheres. But the difference comes with the type of attention needed to perform a particular function. “The left hemisphere produces ‘narrow-beam, highly focused attention,’” like a bird hopping on the grass looking for some worms or seeds. By contrast, the right hemisphere displays a “broad, sustained vigilance.” That same bird, while focused on feeding itself by pecking at the grass, also remains alert to potential predators by quickly looking up and scanning its surroundings. It needs both these types of attention for survival.

In the same way, human beings have always used both hemispheres of their brains to both survive and thrive as a species. Their left brain’s single focus has enabled them to problem-solve and expand their “practical rationality” so as to create a variety of tools to better their environments and organize their communal living. In addition, contextual behavioral science tells us that, unique to our species, we learn also through “contingencies of meaning”—that is, through language and cognition, we put to work our capacity for “symbolic learning.” While practical rationality allows us to learn from the immediate causal chain produced by an action (just as dogs and other animals are capable of doing), many actions produce a second causal chain, one that may be discerned only in retrospect, simply because of time lapse. That is where humans shine. Their right brain uses its sustained attention over time to acquire symbolic learning.

In this way, along with our human capacity for practical rationality, we deploy “substantive rationality,” and as a result we have evolved religious and moral traditions, with each culture developing its particular trove of rules, guidelines, proverbs, myths, which all contribute to its repository of wisdom, allowing its people to lead a good life. Afzaal explains:

“These teachings almost universally emphasize the importance of delayed gratification, self-control, empathy, altruism, sharing, reciprocity, and prioritizing the distant future over the here and now—either for the benefit of the ‘seventh generation’ or one’s own salvation in an afterlife. Similarly, there are prohibitions against waste and greed, against taking more than what is truly needed, against selfishness of all kinds, and against conspicuous consumption” (p. 93).

Thus, in the eighteenth century in particular, with the benefits of the industrial revolution, Europeans drilled down on their practical rationality and sidelined their substantive rationality, either because they thought it had produced outdated notions and superstitions, or because it impeded “progress” and their conquest of other nations. Unfortunately, that mode of industrialization and capitalist organization that requires insatiable consumerism, greed and capital accumulation benefitting the haves and impoverishing the have-nots, has spread globally. Now it is on an ominous trajectory that threatens our survival as a species, and perhaps even life on Earth.

Injecting values in our teaching

It is urgent that humanity restores the rightful balance between our practical and substantive rationality, insists Afzaal. But Business-as-Usual is protected by extremely powerful business interests and a class of billionaires around the world who have a vested interest in the status quo. “Moreover, higher education is part of Business-as-Usual, which is why it must produce the human resources in accordance with what the market needs” (p. 84).

Those are systemic issues that, as individuals, we are powerless to change. But university professors are best placed to sow seeds of awareness of what is to come in their students and the motivation to resist the Business-as-Usual system that currently runs much of their lives. But most academics are not aware, or only partially aware if they are at all, of the coming Collapse of our global civilization. I have no room here to delve into all the reasons Afzaal gives for this. Part of the problem is that academics are forced into silos of specialization and therefore struggle to get the big picture (a right-brain substantive reason function). Another is that they are overworked and poorly paid. Who wants to add to their already heavy load? Let’s admit that to ask someone to change their whole worldview, deal with the added anxiety it creates, and then find ways to tweak their teaching in a way that can bring their students on board—that is a “big ask”!

And yet, if teaching is truly a vocation, and not just a job, then we should find it in ourselves to prepare the younger generation to mitigate the worst harms of today’s Predicament and thereby, if possible, “to manage our [human] response to the ongoing Collapse so that it proceeds in a relatively peaceful, humane, and equitable manner” (pp. 189-90). And it is not as if Gen Z is unaware of some aspects of this Collapse. Think of the global impact of one Swedish school girl (age 15) who in 2018 initiated a strike in front of the Swedish Parliament. Greta Thunberg ended up sitting alone on the steps of the Riksdag during three weeks instead of going to school, holding a sign that said, “School Strike for Climate.” Remarkably, that action sparked a global youth movement calling for decarbonization—the so-called “Friday for Future” movement.

I remembered hearing of a study that documented the eco-anxiety of the youth. I found it. I was published in December 2021 by the journal The Lancet (Planetary Health). The article (“Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey”) to which nine specialists contributed, analyzed a survey of 10,000 youths, ages 16 to 25, from ten countries (Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the UK, and the USA). The Findings in the Summary are worth quoting:

“Respondents across all countries were worried about climate change (59% were very or extremely worried and 84% were at least moderately worried). More than 50% reported each of the following emotions: sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless, and guilty. More than 45% of respondents said their feelings about climate change negatively affected their daily life and functioning, and many reported a high number of negative thoughts about climate change (eg, 75% said that they think the future is frightening and 83% said that they think people have failed to take care of the planet). Respondents rated governmental responses to climate change negatively and reported greater feelings of betrayal than of reassurance. Climate anxiety and distress were correlated with perceived inadequate government response and associated feelings of betrayal.”

Perhaps we can gratefully look back to one or two teachers who inspired us to learn better, or believe in our own abilities, or even nurture our sense of idealism in serving others less fortunate than ourselves. Teaching at Twilight is a must-read for all educators, and honestly, for all of us who have a voice in our children and grandchildren’s lives. As we seek to read more and educate ourselves about our current planetary Predicament, more than anything we are called to pass on a different worldview and model viable alternatives to the pressures of consumerism by living simpler, more communal lives built on sharing. To this end, I believe that those of us who are people of faith have a wealth of spiritual values and sustenance to help us resist Business-as-Usual, love God, care for his creation, and love our neighbors, whoever they may be. We should be taking the lead in this urgent and important task.

This was a sermon I preached at our church on January 4, 2026. It takes account of the New Year and the fact that we had communion that Sunday (many evangelical churches celebrate the Lord's Supper only once a month). But for many of you my readers, Christian or not, you will be interested in the work I highlight of New Testament scholar Ken Bailey and his work with the parables of Jesus. His parents were Presbyterian missionaries in Egypt and then in Lebanon, which meant that he grew up speaking fluent Arabic. After his degree in Arabic literature and a PhD in New Testament studies, he taught for 40 years in Egypt, Lebanon, Israel (Tantur Ecumenical Institute), and Cyprus. He later did some teaching at Princeton Seminary. My wife and I got to know him when he was living in Cyprus, because he would often come to Jerusalem (Tantur is between Jerusalem and Bethlehem). This was in the 1990s when I was teaching in Arabic at the Bethlehem Bible College.

Bailey is known for his meticulous research into traditional village culture in Middle Eastern villages and into the literary structure of Jesus' teaching. In turns out that Jesus was a great poet and wordsmith. This was part of the reason crowds hung on to his words and so easily memorized him.

This is about the parable that has spilled the most ink: the Parable of the Shrewd Manager. It makes little sense in our Western context, but so much more in traditional village culture of first-century Palestine (the Roman appellation of occupied Israel of the time).

As Christmas draws near, I want to comment of the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation, drawing from the first two essays in the latest issue of Christianity Today (Russell Moore, “All I want for Christmas is a time machine”; Deborah Haarsma, “The Incarnation sheds light on Astrophysics”).

My first three posts about Christmas date to 2011, 2012 and finally 2013 (“Honoring the Birth of the Second Adam”). They were all written in the mode of Muslim-Christian dialogue. That’s not the case here, but astrophysicist Deborah Haarsma mentions a 2022 Barna survey of people claiming no religious affiliation, in which respondents said that one of the top reasons that they doubted Christian beliefs was “science.” Therefore, Muslims and Jews reading along will no doubt find some benefit, as we all share a belief in the Creator God and face a society increasingly skeptical about the relationship between faith and science.

The biggest issue, perhaps, relates to “human significance” in light of the unfathomable vastness of our world. In Haarsma’s words,

“In our solar system, the Sun carries the Earth and other planets along as it orbits the Milky Way galaxy, sailing among a vast number of stars of which it is but one.

Astronomers estimate the total number of stars in our galaxy at about 100 billion; the majority are distant and dim, with only a sprinkling of 5,000 or so bright enough to see with the human eye.

Beyond the Milky Way, many more galaxies are scattered along huge filaments throughout space. Some clump together in small groups, like the Milky Way and its neighbor galaxy Andromeda.

Many merge and collide throughout their lives, accumulating mass and birthing new stars. Hundreds or even thousands of galaxies can conglomerate in rich galaxy clusters, which are some of the largest objects known to humans.”

How many galaxies are there altogether? We cannot know, since even with the best telescopes we can only see so far. “But researchers recently measured the collective faint light of the galaxies and estimated that the visible universe contains hundreds of billions of galaxies—each of which contains billions or trillions of stars.”

But there is more: we now know that “27 percent of the universe is dark matter—a scientific mystery that doesn’t emit or block light and that we can detect only by its gravitational effect on other matter.” That is not all: 68 percent of the universe is “dark energy,” a substance even more difficult to apprehend, but which explains the continuous expansion of the universe.

All this to say that science can only account for 5 percent of our universe, including “all the stars and all the atoms on the Periodic Table.” This only reinforces the fact that as human beings we are “dwarfed by both the creation and the Creator.” As David exclaimed in Psalm 8, “When I look at the night sky and see the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars you set in place, what are mere mortals that you should think about them, human beings that you should care about them?” (vs.3-4, NLT). What is more, Paul was likely quoting from an early hymn of the church when he wrote, “for through [Christ] God created everything in the heavenly realms and on earth” (Colossians 1:16). And this same cosmic Christ is, in the words of John the Evangelist, the “Word” that “became human and made his home among us” (John 1:14, NLT).

The Incarnation in the light of current science means that Christ’s virgin birth gave him a body made from the atoms that “have their origins in the heavens”:

“Hydrogen dates back to the beginning of the universe, when protons formed from cooling primordial plasma. Other elements needed for life—like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—arose by nuclear fusion in the cores of stars.” And when “a star dies in a supernova explosion, the atoms are flung into space.” These explosions form new elements as well, like cobalt and nickel.

As Carl Sagan used to say, our bodies are formed of “star stuff.” Haarsma quips, “Through the Incarnation, God himself took on stardust when he took on human flesh.” She adds, “Those atoms assembled into genes to give shape to his bones and blood and into organic chemicals shared with all life on earth.” This means that “[e]ach cell of Jesus’ body embodies his love for his creation,” including all living beings and all the elements of our common home on earth. The cosmic dimensions of the Incarnation also point to God’s dazzling love for the people he came to save and thereby recruit them to live with him in the new heaven and the new Earth which will come together in the New Jerusalem. For then creation will be completely renewed. And above all, God will make his home among his people, his “children” (Revelation 21:7).

The bending of time and space

One of the things Haarsma loves most about astrophysics is that it focuses on phenomena that could not possibly happen on Earth. Albert Einstein discovered, for instance, that gravity is not so much a force (as Newton said) as it is “a distortion of the fabric of space-time.” Thus, light is itself affected by gravity. In fact, the mass of galaxy clusters is so great that “space curves substantially over large [these] distances.” A galaxy cluster, by causing light to bend around it, then becomes a “gravitational lens,” like a warped window distorts the object we see through it.

Yet the theory of relativity teaches us more than “curved space”:

“Relativity describes deep and beautiful symmetries in the cosmos—between time and space, energy and momentum. Moreover, the same laws hold true in every location and circumstance we’ve been able to test. For those who can read the equations, the depth and universality of the mathematics is stunning. Many physicists have thus sensed the divine behind it. In 1948, Einstein himself told his friend William Hermanns, ‘I meet [God] every day in the harmonious laws which govern the universe. My religion is cosmic.’”

As I was initially reading these two essays, I realized that both of them mentioned the warping of time and space—but in very different contexts. I would like to bring them together now. Haarsma mentioned it in relation to Einstein's theory of relativity. In the above quote, she emphasizes how this bending of time and space “describes beautiful symmetries in the cosmos” which scientists can access through mathematics. And as they do so, they are filled with a sense of wonder that for some of them points directly to a Creator.

Russell Moore, editor-at-large and columnist for Christianity Today, begins his own discussion of the warping of time and space with the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration (Mat. 17:1-8; Mark 9:2-8; Luke 9:28-36):

“In that moment on the mountain, Peter, James, and John see Jesus overshadowed with a cloud, incandescent with glory, and hear him addressed by God’s voice. [Moses and Elijah appear, discussing with Jesus his coming death and resurrection]. The moment ties together much of the rest of the biblical story: the pillar of fire and cloud that guided Israel through the wilderness, the teaching of Jesus (summoning them to a mountain), the crucifixion of Jesus, the Resurrection, the Ascension, the glory of the New Jerusalem to come—it’s all there.”

Moore then cites Anglican poet and priest Malcolm Guite’s recent book, Lifting the Veil: Imagination and the Kingdom of God. What if the mountain top experiences of Moses and Elijah (several centuries later), and the Transfiguration itself are one and the same event? Guite wonders, “If Moses and Elijah saw the face of God in a mystery then it could be none other than the face of Christ.” In this case, both time and space were bent to bring these three figures together—from Mount Sinai in the southwest and Mount Carmel in the north, and from the distant past and back. This certainly seems plausible, says Moore, and especially in the case of Moses, whose face as he came down the mountain shone so “painfully brilliant” that it must have been “the glory streaming from the face of the transfigured Christ.”

Moore reminds us that contemporary science has discovered that in our universe—or “pluriverses,” as some scientists call it—space and time interact in very unexpected ways, and we know so little about it as of yet. Yet the lesson from the Transfiguration (even without Guite’s suggestion) nudges us a bit closer to the mystery of how an infinite God can listen with tenderness to the prayers of people throughout the ages and throughout the world in real time. The very fact that he transcends time and space also means that he can be intimately present with each human being that calls out to him.

We know this from the Christmas story. Whether it be the shepherds guarding their flocks that night in the fields near Bethlehem to whom angels appeared with the good news, or with the Wise Men who about two years before saw an extraordinary star in the Persian sky—both groups found their way into the presence of the divine child and his parents, Mary and Joseph. Matthew quotes the prophet Isaiah who about six centuries before spoke about the virgin girl whose child will be called “Immanuel”—God with us.

As we just saw, modern science still knows very little about our universe, particularly about the “distortion of the fabric of space and time.” It’s no great stretch, then, to see the Incarnation of God’s Son as the “gravitational lens” pulling together all the strands of humanity’s history, which itself finds its meaning and purpose in God’s redemptive plan played out in the Bible—from creation to its final fulfillment in the City of God. And better yet, within this great cosmic panorama, I know that I am loved. Jesus was born of Mary so that you and I could become God’s beloved children. John, who witnessed the Transfiguration, also wrote: “But to all who believed him and received him, he gave the right to become children of God” (John 1:12). We know God's loves all his children.

I’ll conclude with these last words of Russell Moore’s piece:

“We can’t relive the past. We can’t peer into the future. We can’t even hold on to the present. In the eternal ’today’ of the God who created and fills and transcends time, we can only know this: God is with us.”

I would not have written this post had I not been part of a foursome virtual book club. One of these friends from my 1970s seminary days in the Boston area had been reading a book by award-winning author specialized in early American history (four awards, including being a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize): Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Eye of the Hurricane: The Genius of George Washington and the Victory at Yorktown. So we decided to read this book and discuss it together.

An expert in the naval battles and other seafaring adventures (including his book, Why Read ‘Moby-Dick’?), Philbrick puts his knowledge to use and argues that the victory at Yorktown was the decisive breakthrough that would lead to the end the Revolutionary War. That’s because that war would never have ended without Washington’s patient bridge-building with and diplomatic pressure on the French navy’s admirals.

Though the French naval victory over the British on September 5, 1781 in the adjacent Chesapeake Bay was technically a standoff, the British suffered so much damage that they had to return to New York for several months of repairs. This prevented them from rescuing seven thousand British and German soldiers holed up in the nearby Yorktown fort. British General Cornwallis’s surrender a few days later was no surprise. Between the 20,000 French sailors in the bay and the 8,000 French soldiers fighting alongside Washington’s 3,000 American militia, Cornwallis knew from the start that the odds were not on his side.

Most history books place almost all of the emphasis of this victory on Washington’s long march south to the Chesapeake in coordination with the French general Rochambeau. As significant as that effort was, Philbrick intends to set the record straight. American historians tend to downplay the Battle of the Chesapeake because no Americans were involved. And yet . . .

Washington’s five years of war before this had taught him that his rebel army, though it had the advantage on being on its own land, Britain’s powerful fleet of warships guaranteed their control of all the coastal cities. He learned early on that without the help of the French navy (and soldiers they were transporting), the Continental Army could not win the war. A humbling thought, is it not? But Washington had become a wise military leader who could seize up the situation as a whole, without letting his own ego stand in the way.

In what follows, I present a few other lessons, focusing on the ones that seem most important to a majority of Americans in December 2025.

Washington’s incredible perseverance

The turncoat Benedict Arnold, once a decorated commander in Washington’s army, was now a British general sent from New York to establish a fortified garrison in Portsmouth, on the southern tip of the Chesapeake coast. Though the French admiral De Ternay had died suddenly, his second in command, Charles Destouches, won a brilliant victory against the British admiral Arbuthnot at Cape Henry in March 1781 but failed to follow through on it and force the British navy to leave the Chesapeake Bay area. Had Destouches done so, the soldiers he was transporting would have joined Washington’s Continental Army and crushed Arnold’s outpost in Portsmouth, and thereby eliminating much of the British threat from the Carolinas to Virginia (the Southern front).

Washington also faced bitter head winds internally. His army was dangerously exhausted, underpaid and underequipped, and Congress was so divided that it could not come up with any more money to support it. Philbrick quotes from some of Washington’s correspondence from the time:

“Not only had Destouches’s unconsummated mission against the British fleet and ultimately Arnold wasted precious resources, it had raised and then dashed the country’s expectations just when ‘we stood in need of something to keep us afloat . . . . Without a foreign loan, our present force (which is but the remnant of an army) cannot be kept together this campaign [sic].’ Washington went on to list some of the other challenges facing the country and its exhausted army such as Congress’s inability to exert ‘a controlling interests over the states’), then stopped himself. ‘But why need I run into the detail when it may be declared in a word that we are at the end of our tether and that now or never our deliverance must come’” (105-6).

This was only five months before the Battle of the Chesapeake followed by the victory at Yorktown. Washington persevered despite seemingly unsurmountable obstacles, that year, and then for two more years. But he could not have won without the French navy dealing a decisive blow against their British foes.

A man of integrity and selflessness

Sometime in 1782, “a colonel in the Continental army had made the mistake of suggesting that Washington be named king of the United States. ‘[Y]ou could not have found a person to whom your schemes are more disagreeable,’ Washington had thundered back in response. ‘[B]anish these thoughts from your mind, and never communicate . . . a sentiment of the like nature.’” Then Philbrick adds, “As they all knew, Washington would never challenge the sovereignty of Congress” (246).

So much more could be said of Washington’s honesty recognized by all. It was paired with his willingness to endure great hardship along with his soldiers over those years, and thereby exemplifying in his own behavior what he commanded them to do. When he was named by the Continental Congress as the commander-in-chief of the newly constituted army, he agreed to serve without pay but on the condition that Congress should pay for his expenses, which they finally did after settling all of his accounts in 1783.

Perhaps his most illustrious selfless gesture was that of stepping down after two terms of presidency at age 64. Young British architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe came visiting Mount Vernon soon after his retirement and wrote in his journal, “He is 64, but appears some years younger, and has sufficient vigor to last many years yet” (278). As it turned out, just three years later, after several hours of riding around his property in the “freezing rain,” he caught a sore throat that infected his lungs. He died a few days later. But the point to remember here is that Washington relinquished power willingly, knowing it was best for the democratic experiment to which he had so handsomely contributed, first as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, and then as its first president.

A man of vision, firmly believing in democracy and a strong central civil government

As the months went by, Washington’s “infected gums and decaying teeth” caused him almost unbearable pain. Also, like many of his contemporaries in their fifties, he suffered from poor vision, even to the point that reading became extremely challenging. He did get some help, but Washington, now with his reddish hair turning mostly white, had obviously aged a great deal with the rigors of eight years of war.

But as a crisis of monumental proportions was brewing in the capital Philadelphia, Washington stood at the ready to help solve it. He was no elected official, but a general, and yet, when he realized that in February 1783 his officers, who by now had lost patience with Congress which still couldn’t manage to pay them their dues after all the sacrifices they had made to save their fledgling nation. So they sent a delegation of three officers to Philadelphia: “Since the states refused to grant Congress the right to collect taxes required to pay the army, the officers had asked that, at the very least, the delegates determine what was owed each of them for future reimbursement. But even this request was encountering resistance” (246).

Washington, who had not been notified by his officers of the matter, grew alarmed. He was now beginning to understand the political rumblings in Philadelphia: some of the congressional delegates were seeing an opportunity to use the threat of the military to force the states to grant Congress the funds they needed to pay the government’s creditors (including the officers) and the power to spend it as they deemed necessary. Washington was well aware that the Continental army had been “terribly mistreated.” But here was the principle he could not bend on: one cannot use military might “to force the hand of civil government.”

Add to the gravity of the situation the fact that these officers had gone behind Washington’s back, thus undermining his authority. In fact, a couple of anonymous letters were circulated among the officers calling for bolder action. The first one called them to a meeting to draw up a plan to force Congress to give them their rightful due. Then it suggested that they “suspect the man who shall recommend moderate measures”—a thinly veiled reference to their leader, George Washington.

When he found out about the letter, Washington issued orders expressing “his disapprobation of such disorderly proceedings.” He then exhorted them to come together after four days, having pondered long and hard about the right course of action in the interest of their cause and in the best interest of their country. In other words, they should convene “after mature deliberation.” He ordered Horatio Gates (the hero of the Battle of Saratoga, and the man he suspected had something to do with the letter) to preside over the meeting and inform him of its proceedings.

Washington had no intention of attending that meeting, that is, until he came across a second anonymous address, which stated that their leader had given them the freedom to chart their own course, whatever that might be. That was patently wrong. But he also didn’t announce his intention to attend. Here is how Philbrick describes the scene:

“Soon after Gates began the meeting at noon, Washington arrived at the door and asked to be given the opportunity to speak. The unexpected appearance of the commander in chief at such an emotionally freighted moment had a riveting effect. According to Captain Samuel Shaw, ‘Every eye was fixed upon the illustrious man’” (248).

He began with an apology for changing his mind and for coming to the meeting unannounced with a prepared speech. He then proceeded to chasten them regarding the use of “an anonymous summons,” which is plainly “inconsistent with the rules of propriety,” “unmilitary,” and “subversive of all order and discipline.” As everyone present knew, Washington himself had struggled over the years to overcome his own “volcanic temper” but had largely succeeded at this point. In light of that, he upbraided the author of the summons for seeking to stir up their “feelings and passions” rather than appeal to “the reason and judgment of the army.” Instead of acting on the whims of the moment, they all should display “cool, deliberative thinking and that composure of mind which is so necessary to give dignity and stability to measures” (249).

More specifically, they should refuse “the appeal of a writer who would ‘overturn the liberties of our country, and . . . open the flood gates of civil discord and deluge our rising empire in blood.” As officers of this young nation, they ought to “give one more distinguished proof of unexampled patriotism and patient virtue . . . and by the dignity of [their] conduct afford occasion for posterity to say, when speaking of the glorious example you have exhibited to mankind, ‘had this day been wanting, the world had never seen the last state of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining” (349).

Despite such an eloquent and thoughtful speech, the officers “remained sullen and unconvinced.” Yet Washington had one more item to share with them: a letter of support for them by the Virginia delegate to Congress. But as he began reading, it became painfully obvious that he had trouble making out the handwritten words. “Gentlemen,” Washington said, “you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray, but almost blind, in the service of my country.” Philbrick then describes how their commander in chief’s vulnerability melted the hearts of his officers:

“No one in the room had ever seen him wearing glasses—a sign of human frailty that overwhelmed them. ‘There was something so natural,’ Samuel Shaw recalled, ‘so unaffected, in this appeal, as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory; it forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye’” (250).

Washington then quickly left the room. The atmosphere was now radically transformed. Several officers “moved that a committee be elected to draft resolutions for Washington to forward to Congress. Soon Henry Knox and two others had produced a statement pledging the officers’ ‘unshaken confidence in the justice of Congress and their country’ and requesting that Washington plead their case for them. The resolutions passed unanimously” (250).

Washington had successfully quashed a mutiny that could have brought down the new nation. A year later, Thomas Jefferson quipped, “the moderation and virtue of a single character has probably prevented this revolution from being closed as most others have been by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish” (250-1).

A man of humble faith

The founding fathers of this nation had at least to some extent been raised Protestant. Many of them had since turned to the Deism, the philosophical belief at the heart of the 18th Century Enlightenment, however (see this Britannica article). George Washington rarely spoke or wrote about religion. He generally attended the Anglican churches where he stayed or lived over the years, but always refused to receive communion. Yet, like many of his colleagues, he was also a Freemason. Not much more can be said, except that “[h]is personal letters and public speeches sometimes referred to “Providence,” a term for God used by both Christians and deists” (see this).

I only bring this up because Philbrick quotes from a letter he wrote in the spring of 1782, commenting on the “hurried rush of seemingly random events” which had led to the victory at Yorktown—from a hurricane in the Caribbean [hence, the book’s title], to a bloody battle amid the woods near North Carolina’s Guilford Courthouse, to the loan of 500,000 Spanish pesos from the citizens of Havana, Cuba” (xiv). Cognizant of these events, Washington concluded, “I am sure that there never was a people who had more reason to acknowledge a divine interpretation in their affairs than those of the United States” (xiv-xv).

Washington’s clay feet revealed

It wasn’t until December 23, 1783 that Congress, barely managing to meet a quorum of twenty legislators, officially received Washington’s resignation. “Having now finished the work assigned to me, I retire from the great theatre of action. . . . I here offer my commission and make my leave of all employment of public life” (261). But duty called again in 1787 as he was asked to preside over the Constitutional Convention and was elected the United States’ first president the following year.

Washington, in the last four years of the war as recounted in Philbrick’s book, leans most heavily on two military leaders, Nathaniel Boone and the young French Marquis de Lafayette. But he was closest to Lafayette who considered him as a father. Washington received a letter from Lafayette in the spring of 1783 asking him to consider a “wild scheme”—buy a plantation together in which they would “try the experiment to free the Negroes and use them only as tenants. Such an example as yours might render it a general practice” (252). Washington answered him with praise for his benevolence and that he would like to join him “in so laudable a work.” But in practice, he did nothing to stop the slave catchers who were mandated to restore to their owners their “rightful property,” and he continued to make use of his own slaves at Mount Vernon. Still, in his will he stipulated that all of his 124 slaves should be freed, “becoming the only slaveholding Founding Father to do so” (280).

Furthermore, in his last years “he’d realized that the greatest threat to the country’s future came from slavery. Jefferson overheard Washington give this ominous warning, “I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union.” And, as if he anticipated the Civil War, he added that should it come to that, “he had made up his mind to remove and be of the Northern [portion]” (279).

None of this, or any other failings or weaknesses—we are all fallible human beings, after all—take away from this man’s great accomplishments. He was certainly a man of his times, but at least as his will demonstrated, he was less so than his Southern contemporaries.

My greatest takeaways from this brief look at Washington’s political leadership are 1) his unshakable conviction that only a strong federal government can preserve the Union; 2) his deep respect for the rule of law and the separation of powers; 3) and finally, his example of unwavering integrity and personal sacrifice for the common good of the people. He was a model of public service.

Sadly, these are qualities plainly lacking in our current president. May we take these qualities into account as we elect our next president in 2028.

The Rev. Thomas J. Reese became a Jesuit priest in 1964 after earning a PhD political science at UC Berkeley, but he has mostly served as a journalist and academic. I find his pieces in Religious News Service consistently informing and thought provoking—including this one from a couple of months ago, “Amos, a prophet for social justice, is a prophet for today.” I quote,

“Anyone who thinks the Scriptures are not political has never read the Prophet Amos hurling invectives at the rich and powerful of his time.

Amos was not a professional prophet, but an uneducated shepherd who preached social justice and denounced exploitation of the poor by the rich. He was especially harsh on the rulers, priests and upper classes. His words sound like a political activist ranting on MSNBC.”

Amos blasted the rich who used their power to grind the poor into the ground, while stealing from them to enrich themselves even more. “They trample the heads of the destitute into the dust of the earth, and force the lowly out of the way,” he declared. Judgment will come because they live in luxury while turning away from the suffering of the destitute and oppressed in the land.

Religion won’t save them. Only repentance and a commitment to practicing justice will:

“‘Take away from me your noisy songs,’ Amos had God saying. ‘The melodies of your harps, I will not listen to them.’

‘Rather let justice surge like waters, and righteousness like an unfailing stream,’ he said.”

Rached Ghannouchi’s post-exilic political trajectory

Tunisian cleric, writer and politician Rached Ghannouchi would agree with Amos. Religion properly understood—Islam in this case—cares about good governance, which is about distributing power justly so as to alleviate poverty and finding ways for all to thrive.

I mentioned him in my last post, while exploring some of the common theological resources in Judaism, Islam and Christianity for making this world a more peaceful and just one. I cited Ghannouchi, whose classic book, Public Freedoms in the Islamic State, I was privileged to translate. Since then, I ran across an article by one of his daughters, Soumaya Ghannoushi, an accomplished British journalist. This piece was published a couple of weeks ago in Middle East Eye with the title, “My father’s ideas will outlive this shameful era in Tunisia.” But first, a bit of background will help.

Ghannouchi, whose only crime was to have co-founded a religious party that did so well at the polls that it posed a threat to Tunisia’s autocratic ruler, spent most of the 1980s in prison. He was fortunate to escape his death sentence but was exiled for twenty years in the UK. From there he was invited to speak to Muslim audiences around the world advocating democratic governance based on human rights and the dignity of the human person as taught by the Qur’an and modeled by the Prophet Muhammad’s rule in Medina (622-632). In essence, Ghannouchi is an Islamic religious leader (he is referred to by many as “Shaykh Ghannouchi”) who has specialized in political theology. But he was more than an academic.

As the “Arab Spring” swept through Tunisia in December of 2010 and the daily mass protests literally ousting dictator Ben Ali the next month, Ghannouchi returned to his country to a hero’s welcome, and his party, Ennahda (“The Renaissance”), became the ruling party in the parliamentary elections that fall. At a time when neighboring Libya was falling into chaos and civil war, some of that violence spread to Tunisa and his party was blamed for two high-profile assassinations.

That is when Tunisia’s three largest trade unions and its League for Human Rights came together (the so-called "Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet”) to call the political elites to the drawing board in order to draft a new constitution that would enshrine the recent democratic gains and point the way forward in that time of crisis. Ghannouchi, the leader of the ruling party, led the way by leaving the government and joining the process of rewriting the constitution. When that new constitution emerged, Ennahda agreed to ratify it, despite its little mention of Islam and the absence of the word “shari’a” (a key word relative to Islamic law).

The following year (2015), the Nobel Peace prize was awarded to the “Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet.” Here was my commentary shortly after it was announced:

“That said, the Quartet’s work could not have succeeded had their advocacy with Ennahda, the ruling party, not borne fruit. Ennahda did what rarely any party has done anywhere else, by stepping down from power before their mandate had come to an end. True, the country had been shaken by the assassinations of two secular opposition politicians that year. Still, the fact that Ghannouchi’s Ennahda willingly gave up power to join the other political forces in the country in drawing up a new constitution and reconvene a new set of parliamentary elections in the next year is nothing short of phenomenal.

Ennahda, among all other political currents, was justified in taking some credit for this honor [the Nobel Peace prize]. Thanks to all the political factions, the so-called Arab Spring would continue to live on – with all its ups and downs – in the land where it was born.”

Then, in his opening speech at Ennahda’s Tenth Congress in 2016, Ghannouchi declared that Tunisia no longer needed “political Islam.” Democratic institutions, if well-crafted and guarded, will always ensure that the people will elect those who embody their values. The Tunisian nation is overwhelmingly Muslim and if the majority prefers a more secular interpretation of what that means politically, then Ennahda will cooperate with secular parties to forward the common good for all Tunisians. It thereby was relinquishing any promotion of its own interpretation of Islam in the public sphere and was announcing it would function just like any other political party vying for support for its public policies.

At that stage, Ghannouchi himself decided to run for election. He easily won a seat in the Tunisian parliament and in 2019 was elected by his peers as speaker of parliament. But then the specter of dictatorship reared its ugly head once again. As his daughter puts it in her article, “Tunisia’s misfortune is that into the space opened by that democratic experiment stepped a populist fanatic who understood democracy only as a ladder. [President Kais] Saied climbed it to reach power - then kicked it away.”

A political outsider, Kais Saied was elected president in 2019 but then suspended the Ennahda-led parliament in 2021 and ruled strictly by decree from then on. He imprisoned several opposition leaders, but as his rule was facing fiercer resistance in February 2023, Saied launched a harsher campaign of repression, arresting two dozen opposition leaders, activists, journalists and judges. Finally, he arrested 82-year-old Ghannouchi himself in April. And two years later, Ghannouchi still sits in a small cell behind an iron door, one of the oldest political prisoners in the world.

Ghannouchi’s current hunger strike

Soumaya, his daughter writes,

“Last week, my 84-year-old father, Rached Ghannouchi, embarked on a hunger strike.

His body is frail, his health fragile; yet from his narrow cell, he chose hunger - not as escape, but as solidarity. He did it for Jawhar Ben Mbarek, a left-leaning professor of constitutional law, one of the leaders of the National Salvation Front and a central figure in the opposition to Tunisian President Kais Saied’s coup.

Ben Mbarek had already been on a wildcat hunger strike for a week, hovering between life and death, when my father joined him. Since then, the strike has spread across Tunisia’s prisons, gathering a growing number of political detainees who refuse to bow to the cruelty of the regime.

It is the last language left to those whom tyranny has silenced: the language of the body, the eloquence of refusal.”

This costly act of solidarity for the sake of his country is Ghannouchi’s clarion call for unity in opposition to the man who chose to monopolize political power in his own person. Will Ben Mbarek—or will he himself—survive this ordeal? They may not, but as his daughter notes, “Even now, the cracks are visible.” She adds, “The regime is hollow, exhausted, without a future. There is a growing conviction that change is inevitable; that the darkness is already thinning at its edges.” This “shameful interlude in Tunisia’s long story” will soon end, and no matter what happens in the weeks and months to come, “My father’s ideas will outlive it, as they have outlived every prison, every slander, every tyrant.”

Upon receiving his death sentence in 1987, Ghannouchi said, “As for my execution - if my blood is shed, I pray to God that it will be the last blood spilled in this country. And I pray that my blood may turn into a rose from which freedom blossoms.” This remains his prayer, 38 years later, once again in prison and now engaging in a hunger strike.

Good governance, from Amos to Ghannouchi

Political theology, simply put, is to think about what makes good governance using the resources of our sacred texts, whether we be Jews, Christians and Muslims. Amos, as we saw, castigated Israel’s rulers, religious leaders and the rich for trampling on the rights of the poor. In the book I just wrote (see this), political theology is one of three main themes. I will simply quote here from the only psalm attributed to Solomon, which is very much about political theology. Solomon is plainly expressing the views of his father, King David:

“Give your love of justice to the king, O God, and righteousness to the king’s son.

Help him judge your people in the right way; let the poor always be treated fairly . . .

He will rescue the poor when they cry to him; he will help the oppressed, who have no one to defend them.

He feels pity for the weak and the needy, and he will rescue them.

He will redeem them from oppression and violence, for their lives are precious to him” (Psalm 72: 1-2, 12-14, NLT).

Importantly, political theology is also applying the principles of just rulership to one’s specific historical context. Solomon, like his father, was a king with nearly absolute power. This psalm is actually a prayer, asking God to grant the king his own love for justice and compassion for the poor and oppressed. To what end? To ensure that all might prosper as much as possible—in the name of equity and equality. But without this commitment to ruling according to God’s commands, kingship tends toward despotism. And in fact, the Israelite monarchy did devolve into despotism politically, and, despite a few good kings along the way, Israel’s kings became more and more corrupt, rebelling against the law of Moses and thus leading the people into the idolatry of the nations around them. And so, God’s warning to the prophets came to pass: Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians and the people were taken into exile.

Ghannouchi’s political theology, by contrast, starts with God’s love of justice as taught in the Qur’an and modeled by Muhammad, the prophet and ruler of Medina, but then takes stock of the world as it is today. The principles of democratic rule, along with the development of international law based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, are the result of the world’s nations coming together after two cataclysmic world wars and declaring that peace is only possible on the basis of strong institutions. Only a stable democratic polity can guarantee freedom and justice for one and all, and thereby ensure a peaceful society. This is why Ghannouchi fought despotism all his life in his beloved Tunisia, convinced that this was the teaching of Islam.

I’ve been to several “No Kings!” rallies this year in Washington, DC, Wilmington, Delaware, and locally as well. The dramatic rise in authoritarian rule and intentional erosion of democratic institutions in the United States is certainly concerning. But we still have the freedom to publicly air our views and protest! That is not an option in Tunisia and many other nations. Let us take inspiration from Shaykh Ghannouchi’s lifelong integrity and courage, and ask God to preserve his life, cause this despotic regime to fall, thus freeing all political prisoners and embarking Tunisia once again on the path of freedom and democracy.

And may his life also inspire us to keep freedom and justice for all burning bright in our own nation!

I end this series of eight posts on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the prospects of ending it by framing the issue theologically. I am a Christian theologian, after all, and I spent my second career researching and writing about Muslim-Christian dialogue. And since the first and greater part of the Bible is the Old Testament, or the Hebrew Bible, and since Jesus himself was Jewish and considered his message to be in line with the Hebrew prophets, we Christians recognize (or should, at least) that we do theology starting with the Hebrew scriptures. My conclusion, therefore, draws strands from all three traditions and argues that there is plenty of common ground to inspire, guide and sustain our collective efforts as aspiring peacemakers.

Prominent Jews who prioritize a more peaceful and just world

Arguably one of the most influential Jews in the world, Professor Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University, economist and public policy analyst, directs Columbia’s Center for Sustainable Development and has been a special advisor to the last four secretary-generals of the United Nations—first, on the eight Millennial Development Goals (MDGs, 2000-2015) and then on the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (2015-2030). Having devoted most of his life to find ways of eradicating extreme poverty, he has expanded that goal with scientists and policy makers from all over the world based on the conviction that only through global cooperation can we solve humanity’s most pressing problems.

Besides the specter of climate change, the pollution of our air and seas, the challenges to agriculture and the health of our great cities, the festering of wars in Ukraine, Sudan, and Israel-Palestine also loom large on the global horizon. Despite the shaky ceasefire underway in Gaza, for instance, the prospects for a just resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are still dim, to say the least. Israeli settlers in the West Bank continue to kill Palestinians as the IDF looks the other way; more homes are demolished and more families are internally displaced. I read this morning that Israel is poised to approve 2,000 new settlements in the West Bank! Meanwhile, at least 150 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza during the ceasefire and the IDF shows signs of digging into their positions for good.

Jeffrey Sachs has also been speaking out on the Gaza conflict. Watch him being interviewed on Breaking Points at the end of August 2025. What he says still applies: “In this most dangerous moment since WWII,” he recommends that the UN General Assembly suspend Israel’s membership in the UN, “because I believe this is a completely lawless, murderous, genocidal regime. I don’t think there’s any other country in the world remotely doing what Israel is doing in terms of the violence, the mass murder and the mass starvation.”

Just a week ago, 460 “former Israeli officials, artists, and intellectuals” called on heads of state to respond to “the underlying conditions of occupation, apartheid, and the denial of Palestinian rights” that are left unaddressed by the current ceasefire. Notice that as they appeal to the UN secretary general and all world leaders, they’re urging them “to uphold international law, halt arm sales and impose sanctions, as well as insuring the flow of humanitarian aid to Gaza.” This demonstrates a “universalist” vision of Jewish identity rather than a nationalist one.

A Jewish American theology opposing Jewish nationalism

While many American rabbis during WWII actively called for Jews to fight for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine still under British Mandate, many Jewish Reform leaders in 1942 founded the American Council for Judaism. Under the “Who We Are” tab on their website, we read that the ACJ aimed “to uphold Reform Judaism as a tradition dedicated to universal ethics and justice at a time when many Jewish institutions began centering Jewish nationalism through Zionism.”

Its current executive director, Rabbi Andrue Kahn, wrote a piece for Religious News Service on the occasion of the Jewish New Year this fall, “Rosh Hashana helps us envision a Judaism beyond nationalism.” This is a theological move. What do I mean by that? First, Rosh Hashana reminds Jews that they are part and parcel of the world God created, writes Kahn:

“On this holiday, Jews do not celebrate the birth of a single people, but the creation of the world. The image is expansive: Every creature passes before the Creator, every being is judged, every life matters.

That vision undercuts the narrowness of a falsely homogenizing peoplehood. It reminds us that the Jewish story is bound up with the story of all humanity — as Jews have dwelled among all humanity. Torah is a wisdom tradition carried in Jewish form and meant to be tested, adapted, shared and lived out in relationship with the rest of the world.”

I would add that this universalist vision dovetails with many passages in the Hebrew Bible. The Psalms, for example, proclaim God’s care for all nations (and all of his creatures):

“Worship the Lord in all of his holy splendor. Let all the nations tremble before him.

Tell all the nations, ‘The Lord reigns!’

The world stands firm and cannot be shaken. He will judge all peoples fairly” (96:8-9, NLT).

The Hebrew prophets often give messages that concern other nations, and at times, all of creation. In this passage in Isaiah, one of the messianic “Servant of the Lord” ones, we read:

“Look at my servant, whom I strengthen. He is my chosen one, who pleases me.

I have put my Spirit upon him. He will bring justice to the nations . . .

He will not falter or lose heart until justice prevails throughout the earth.

Even distant lands beyond the sea will wait for his instructions” (Is. 42:1, 4 NLT).

Jesus picks up this universal strand and John translates it through a vision he receives at the very end of the Bible:

“Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth . . . And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven like a bride beautifully dressed for her husband . . . I saw no temple in the city, for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its temple. And the city has no need of sun or moon, for the glory of God illuminates the city, and the Lamb is its light. The nations will walk in its light, and the kings of the world will enter the city in all their glory” (Revelation 21:1-2, 22-24 NLT).

Rabbi Kahn then makes a second related point, not directly theological, but as a historical application of that first point’s theology:

“For most of Jewish existence, there was no unified ‘Jewish People.’ Jews have lived and thrived heterogeneously in places as widespread as Aleppo, Mtskheta, Addis Ababa, Baghdad, Sanaa and Cochin, each with distinct practices, customs and self-understandings. They often disagreed sharply with one another, and rarely imagined themselves a single, homogeneous nation.

Instead of nationalism, Jewish collectivity was mythopoetic: a spiritual understanding of covenant via Torah, which expressed itself in many differing, and often mutually exclusive, forms throughout the world.”

The “Jewish story,” he remarks, “is bound up with the story of all of humanity. Thus, the towering twelfth-century Jewish philosopher and Torah scholar Maimonides who lived in Spain, Morocco and later in Egypt, once said to a convert that “Abraham’s lineage is spiritual, not genetic.” Rosh Hashana teaches Jews that “Jewish distinctiveness is real, insofar as it complements the distinctiveness of each facet of the whole of humanity.” The linking of Judaism and Jewish identity with a modern nation-state is just that—a modern invention, says Kahn.

The universalist message of the Quran

This will be brief, as I have written extensively on this topic elsewhere, and in two books, in particular. Though the Islamic tradition is just as diverse as the Jewish and Christian ones, all Muslims will agree that God created humankind and delights in its many hues and cultures:

“People, We created you all from a single man and a single woman, and made you into races and tribes so that you should recognize one another. In God’s eyes, the most honoured of you are the ones most mindful of Him: God is all knowing, all aware” (Q. 49:13, Abdel Haleem).

The only difference God makes among human beings is the degree to which they choose to obey him. Another central theme of the Quran is that of justice. About fifty verses teach how important justice in human relations is to God, and many more proclaim how detestable injustice is to him, and especially social injustice. Here is perhaps the most famous verse:

“You who believe, uphold justice and bear witness to God, even if it is against yourselves, your parents, or your close relatives. Whether the person is rich or poor, God can best take care of both. Refrain from following your own desire, so that you can act justly – if you distort or neglect justice, God is fully aware of what you do” (Q. 4:135, Abel Haleem).

I wrote a series of blog posts on justice in 2013, mostly summarizing a series of lectures I had given at a Muslim-Christian conference in Singapore just before (Justice and Liberal Democracies; Jesus and Justice; Justice in Islamic Law and Ethics; and Justice, Shari’a and Hermeneutics). I concluded “that ‘justice’ as the convergence of such ideals as fairness, dignity for all human beings, human rights and equality before the law, and especially vindication, redress and affirmative action for the downtrodden – justice is a basic aspiration that all people share.”

Justice, then, is not only an ethical ideal we strive for in our relationships with others as we navigate family relationships, or in our dealings with neighbors, or with bosses and colleagues at work. It is also not just about courts of justice where crimes are prosecuted, disputes are arbitrated and victims compensated. Justice, crucially, concerns governance—whether on a municipal, city, regional, national or global scale.

I was commissioned to translate a book written by Tunisian activist Rached Ghannouchi who had co-founded a political party to contest the autocratic rule of the dictator in power since Tunisia’s independence from France, Habib Bourguiba (1956-1987). Happily for Ghannouchi, their political party, steeped in the discourse of political Islam (or Islamism) that was growing in popularity in North Africa and the Middle East since the 1970s, was growing rapidly. Sadly for him, that success cost him his freedom, and while in a state prison most of the 1980s, he wrote a well-researched book, Public Freedoms in the Islamic State, arguing that if rightly understood, the Islamic tradition teaches the importance of democracy (people hold ultimate sovereignty in any state), human rights, and the rule of law, including international law.

While working on this ambitious project (the English version has 570 pages), I wrote a trilogy of blog posts on Ghannouchi, the first, to trace the rise of Islamism in North Africa since the 19th century; the second, to sketch Ghannouchi’s biography; and the third, to explain the trajectory of his influential thought, from a young aspiring politician to the leader of the main political party now in power after the popular uprising (the very first in the so-called “Arab Spring” of December 2010) that forced Tunisia’s second dictator to flee the country.

Then in 2016, at the Tenth Congress of the Ennahda (Renaissance) Party, Ghannouchi declared in the opening speech that “political Islam is no longer needed in Tunisia.” As I explained in a later post, “Ennahda was no longer a religious party but a democratic party among others, whose members nevertheless found inspiration in the ethical values of their Islamic faith.” The book’s original title could have been revised. He no longer wanted an “Islamic state,” but rather a democratic one in which the large majority of citizens are Muslim and are free to express their own preferences for how it should be governed. Ghannouchi also declared in that speech that members of the party would have to desist from leadership positions in their mosque, and that religious leaders could no longer be involved in the party. In other words, no more overlapping of religion and state. And no Islamic nationalism***.

I will just quote a passage near the end of the book, some of which was revised, as you can imagine before its publication in English in 2022 to give you a feeling of the universalism of Ghannouchi’s thought—and indeed of many leading Muslim leaders, scholars and politicians today:

“God has also made the loftiest declaration to humanity, that they are all His creation, and that they all come from one origin and are equally honored and urged them to be as He intended—that is, one family that competes in doing good and repelling evil, in discovering the treasures of this universe and using them to fulfill their material and spiritual needs through many sorts of clues He has graciously dispersed through His creation. Some of these are useful for bettering their lives and others are simply signs of beauty that point to His majesty. Equally, He has forbidden them to arrogantly put anyone down and discriminate against one another on the basis of race, skin color, gender or class, or a claim to piety. For all are brothers and sisters, and thus must get to know and help one another without injustice, and He has granted their minds absolute freedom of conscience and a full responsibility to choose their own destiny” (p. 428).

Wrapping up this series on Israel-Palestine

I began this series by explaining why there had been a 14-month hiatus in my blog writing—after several years of reading, interviewing, and taking notes, I devoted nine months to actually writing the book that became, The City Where All May Flourish: The Holy Spirit in Mission and Global Governance. I mention this again because I wrote this series very much in the spirit of that work. The Apostle John’s vision recounted at the end of the Bible in which the nations of the world stream into the city where heaven and earth have finally become one and where God now literally lives among his people—that city, where human beings from all ages, nations, races and cultures flourish together in God’s presence amidst a creation now completely renewed, serves as inspiration and even blueprint for the kind of world he calls us to work for now.

I argued that it was God’s Holy Spirit who engineered the founding of the United Nations and the drafting of Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the ashes of World War II, both of which inaugurated a long period of relative peace and the drawing up a body of international law. I also urged Christians, often tempted as Jews and Muslims are to resort to religious nationalism, which inevitably tramples on the rights of minorities, and in the case of the United States, builds on the myth of American exceptionalism and intentionally tears down the institutions and treaties that have upheld global cooperation now for decades. Finally, in the case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it takes the side of Israel and rubber stamps its extreme religious nationalism which has recently veered from generic apartheid to ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Yet peace is eminently possible, if only the State of Israel complies with numerous Security Council resolutions since 1967 by dismantling its military occupation of Gaza and the West Bank and negotiates in earnest with its Palestinian counterparts a just and sustainable two-state solution. In the meantime, just as the international community did to bring down the apartheid regime in South Africa, we must all work together to apply maximum pressure on Israel through boycotts, divestment, and sanctions (BDS). With God’s help, we can get this done together and achieve a lasting peace.

*** Rached Ghannouchi was elected speaker of Tunisia’s parliament in 2019, but as a result of a coup engineered by President Kais Saied in 2021, he was jailed along with other opposition figures and in 2025 sentenced to 14 plus 6 years on several trumped-up charges. Join me in praying for his release. He is now 84.

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), an international news agency going back to 1917 with stellar journalistic credentials, ran an article in mid-August 2025 with the title, “Jew vs Jew rhetoric breaks hearts in a bitter internal debate about the Gaza war.” In it, Andrew Silow-Carroll argues that almost two years into this Gaza war, “the Jewish conversation has shifted”: “Jews who have taken to social media to condemn Hamas, anti-Israel protesters and the colleges and politicians they say have enabled antisemitism are now turning on fellow Jews — and not just anti-Zionist Jews, who if anything united the mainstream in a common disdain.”

And who are these two groups of Zionist Jews that are battling it out? On one side you have the “fierce defenders of Israel” and on the other, the “troubled” defenders (“troubled” about the sheer number of people killed and the use of starvation as a weapon of war). And the vitriol has spread like a cancer on social media. We read in one recent JTA opinion piece, “I find myself calling out: Don’t you get that we are at war with ourselves? And we have to find a way to put the pieces back, perhaps to create something new, or we will not survive.”

In this installment in my series on Israel-Palestine, I’ll look at three particular divides in the Jewish community; and I will close with a discussion particularly arising in Orthodox circles—a discussion I find encouraging.

The Israeli-US Jewish divide

In May 2025 a poll in Israel found that 82 percent of Israeli citizens wanted to expel Gazans and 47 percent supported killing them all. The Israeli survey done in partnership with Penn State University was published in the major Israeli newspaper Haaretz. And the more religious people are, it found, the more they favor ethnic cleansing and genocide. The Israelis in the survey are divided into secular, traditional religious, Orthodox, and Haredi (often called Ultra-Orthodox). The secular Israelis are the most reticent to move in these directions and the Haredi go the farthest. Finally, “the younger the Israeli is, the more likely they are to be far-right extremist,” the survey showed.

My immediate reaction in reading “82 percent” was: what about the 21 percent of Israeli citizens who call themselves “Palestinian Israelis”? The article by Ben Norton, founder and editor of the Geopolitical Economy Report where this article is posted, confirmed my own hunch: these Israeli citizens “are not considered to be fully Israeli. They are third-class citizens, and are denied equal treatment by the Israeli regime.” Netanyahu managed to pass the “basic nationality law” in 2019, and on that occasion, he declared publicly “with pride”: “Israel is not a state of all its citizens.” Hence, the “82 percent” are all Israeli Jewish citizens.

Norton mentions an interview in May 2024 in Haaretz with former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert (2006-2009) from Netanyahu’s own party (Likud), who admitted that up to 2024, he denied that the Israeli regime was committing war crimes, but he now believes otherwise. Israel is deliberately using hunger as a weapon and committing “a war of extermination”:

“There are too many cases of brutal shooting of civilians, of destruction of property and homes. Looting of property, thefts from homes, which in many cases IDF soldiers have also taken pride in and published in personal posts. We are committing war crimes.”

He later added that the Israeli army is acting “recklessly, carelessly, and excessively aggressively.” What is more, Israelis “massacre Palestinian civilians in the West bank as well, and commit heinous crimes every day in the West Bank.”

All that said, you know from another post in this series, that the Israeli peace movement is stirring again and at least two Israeli human rights organizations are publicly condemning “our genocide.” Stunningly as well, over “600 retired Israeli security officials, including some former heads of intelligence agencies,” sent President Trump a letter in early August 2015 calling on him to increase pressure on Israel to stop its war in Gaza and secure the release of all hostages, because in their judgment “Hamas no longer poses a strategic threat to Israel.” This doesn't mean they are pressing for a two-state solution to the longstanding conflict. But at the very least, they want this war to stop immediately.

The situation is very different in the United States, where “a majority of American voters now oppose sending additional economic and military aid to Israel, a stunning reversal in public opinion since the Oct. 7, 2023 attacks.”

In a Times/Siena poll just out this week, we learn that . . .

In light of this, it’s no surprise that the American Jewish population also reflects this trend. Another factor that pushes them in this direction is their strong distaste for President Trump and his weaponizing of antisemitism to assert his control over universities. In a poll that came out in May 2025 by GBAO Strategies (“a longtime pollster of Jewish public opinion”), we learn that “three-quarters of Jewish voters (74%) disapprove of Trump’s job performance (70% ‘strongly disapprove’). Most American Jews think Trump is ‘dangerous’ (72%), ‘racist’ (69%) and ‘fascist’ (69%).” In particular, . . .

The US generational Jewish divide

In contrast to Israel where being under 30 tends to correlate with stronger right-wing views, young American Jews tend to be less attached to Israel and more critical of it. The same GBAO Strategies poll mentioned above informs us that . . .

“. . . among younger American Jews, fewer are concerned about antisemitism. While 95% of Jews over 65 said they were concerned about antisemitism, 77% of Jews aged 18-34 were. Asked their concerns about antisemitism on college campuses, 65% of younger Jews expressed concern (39% were ‘very concerned’).”

“Seven in 10 Jews aged 18-34 (71%) believe deporting campus protesters increases antisemitism. Attachment to Israel is also lower among this age group, with 55% saying they are emotionally attached to Israel (24% say they are ‘very attached’).”

Peter Beinart, an American Jewish journalist in his 40s known for his uncompromising critiques of Israeli policies, was interviewed recently on the occasion of his new book’s release, Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza: A Reckoning. Without minimizing the brutality of the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks, Beinart, a Modern Orthodox (see below) Jew originally from South Africa, believes that Israel’s response to it (“a horror,” he argues) makes it ethically impossible for her to continue using “the virtuous victim trope.” He explains, “By seeing a Jewish state as forever abused, never the abuser, we deny its capacity for evil.” What has been “very difficult and painful” for him, however, is that there has been “no reckoning with what it means for us that an entire society is being destroyed—that most of the buildings, hospitals, the schools, the agriculture, the entire basis of life for a population of 2 million people.”