-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

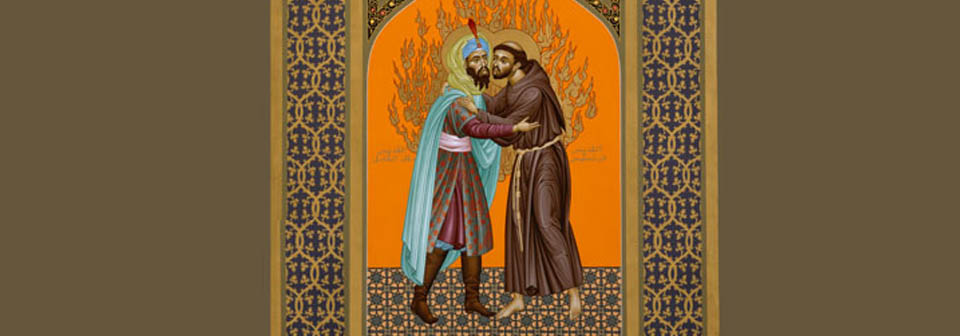

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

In this third installment in my series on Israel/Palestine, I advance a bold hypothesis, one which cannot possibly be defended on scientific grounds. But I do so on the basis of my personal experience in Israel-Palestine from 1992-1996 and several visits since then, including a five-week research stay in 1999 (in Bethlehem and Hebron). I’ve also read a good deal about the issue.

I am proposing that one way to explain the violence and brutality of Zionist settlers since the 1920s and of Israeli leaders during and after the 1948 founding of the State of Israel is to see it in light of psychological research on children suffering abuse. This research shows a likelihood that these children will in turn abuse their own children if they do not get significant trauma therapy (see this 2021 article in Psychology Today commenting on a 3-decade-long study published that same year, “Intergenerational transmission of child maltreatement in South Australia, 1986-2017: a retrospective cohort study”). Here is the relevant paragraph in the Psychology Today article:

“After establishing a clear link between mothers who suffered abuse or neglect during their childhood and the likelihood of their kids experiencing the same fate, the researchers emphasize the importance of supporting survivors of childhood maltreatment early in life and into adulthood as a critical step towards breaking this vicious cycle and protecting the unborn children of future generations from maltreatment.”

That parallel is far-fetched, you might say. After all, these are mothers who suffered from traumatic mistreatment growing up and who are at least 30 percent more likely to reproduce that same behavior toward their own offspring. But then you jump to the macro level and apply something that concerns individuals to a whole people group (the early Jewish newcomers to Palestine in the 1900-1920s were from Europe—known as Ashkenazi Jews). Add to that the fact that the Holocaust didn’t happen till late 1930s-1945.

Still, I will argue, the Jews as a people endured grievous hardship, from the four centuries of slavery in Egypt to the Babylonian exile; from the persecution under the Greek ruler Antiochus IV to the violent expulsion of the Jews from Palestine by the Romans in 70 CE (read this Jewish page, “The Four Exiles of the Jewish People”). Then from the times of the Crusades (1099 CE) to the 1930s, Jews suffered pogroms and all manner of abuse from Christians in Europe. Jews bear in their souls the pain and trauma of many terrors past.

Early Jewish terrorism in pre-WWII Palestine

The best historical work on this period was also Winner of the National Jewish Book Award—Bruce Hoffman’s 650-page Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel, 1917-1947. Adam Kirsch’s review is entitled “Israel: The Original Terrorist State.” Hoffman’s research was based on the newly declassified documents of the British MI5. Here’s his opening summary of the book:

“From 1944 until 1947, Palestine witnessed a series of assassinations, abductions, and bombings, perpetrated by Jewish terrorists against the occupying British. During that period, some 140 British soldiers and policemen were killed, along with dozens of civilian bystanders. In the end, the terrorists got what they wanted, when Britain announced its intention to withdraw all its forces from Palestine and leave the fate of the country up to the fledgling United Nations.”

Naturally, this was not the only factor leading up to Israel’s independence in 1948. You should add the British Empire’s decline; the fallout of the Holocaust, with the United States putting immense pressure on the British “to admit Jewish refugees into Palestine”; finally, you must factor in the Jewish success in creating the infrastructure for a state, “complete with an illegal but tacitly tolerated army, the Haganah.”

“Still,” writes Kirsch, “it is possible that none of these factors would have succeeded in winning Israel’s independence, if the Jewish campaign of terror hadn’t raised the cost of the British occupation so high.” The story is “riveting”: how the waning superpower of the day is brought to its knees by “a few thousand determined militants”—the Jewish “anonymous soldiers.” The largest of the militant paramilitary organizations that broke away from the Haganah was the Irgun. Starting in the late 1930s, its foot soldiers assassinated dozens of British officials and law enforcement officers, though Arabs remained their main targets (the latter had attacked them first), mostly planting bombs in cafés and markets.

The Irgun’s “bloodiest attack” was masterminded by a new arrival from the Soviet prisons, Menachem Begin (who later became prime minister), the bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people in July 1946.

The Daleth (or Dalet) Plan

Ilan Pappé, a prominent member of Israel’s so-called New Historians, is a professor at the University of Exeter (UK), where he also directs the European Centre for Palestine Studies. His 2006 book, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, documents the deliberate driving out of 750,000 Palestinian refugees from March 1948 to the armistice signed with the Arab nations the next year (see this helpful summary page by the Institute for Middle East Understanding—IMEU; see also this blog post by Ilan Pappé on the fiftieth anniversary of the State of Israel). These are the original Palestinian refugees, some of whom moved to Gaza, and others ended up in refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan. Another 300,000 were forced out by the 1967 war when Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights.

The official document laying out the plans for the campaign of terror that would drive out the maximum number of Palestinians from their towns and villages to make room for the coming Jewish state was called Plan Dalet. The IMEU page offers this translated excerpt from that document:

“Destruction of villages (setting fire to, blowing up, and planting mines in the debris), especially those population centers which are difficult to control continuously...

“Mounting search and control operations according to the following guidelines: encirclement of the village and conducting a search inside it. In the event of resistance, the armed force must be destroyed and the population must be expelled outside the borders of the state.”

Over 400 Palestinian villages were completely destroyed as a result and thousands of Palestinians left urban centers like Jaffa, Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem fleeing the violence. Bishara Awad, the founder and director of the Bethlehem Bible College where I taught for three years in the 1990s, tells the story of how his father was killed by a sniper bullet in what is now West Jerusalem (Jewish side) and how he fled with his mother and siblings to Bethlehem, leaving everything behind.

What about today?

A lot of water has gone under the bridge since then—something I will touch on in the next couple of posts. But what is sure is that the Hamas attacks on Israeli soil in October 2023, with the killing of over 1,200 Israelis living nearby (keep in mind, though, that 300 of those were Israeli soldiers and that dozens of Israeli citizens were killed by the IDF as they had orders to use all means possible to avoid the taking of hostages) and the kidnapping of over 250 hostages, touched a deep nerve in the Israeli psyche. My wife and I learned something important in our three years in the West Bank. Foreigners who had lived for a good while in Israel told us that Israelis had founded their nation in the shadow of the Holocaust, and that their founding motto was “Never again!” That understandable cri du coeur—a vow born of trauma—goes a long way to explain, I believe, Israel’s violent and oppressive treatment of the Palestinians in their midst.

In the 1990s and up to maybe 2007, a majority of Israelis were in favor of some version of a two-state solution. Israel had an active and committed peace movement in those days. Since Hamas took over Gaza in 2007 and, starting with the four “little wars” (2008, 2012, 2014, 2021) that killed 4-5000 Gazans, and then leading to the present war, that deep-seated trauma in the Israeli soul has been reactivated. The peace movement dwindled considerably since then.

The current Netanyahu far-right government represents the most radical elements of the Israeli political spectrum. The finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, in a speech to the Israeli Knesset in 2021, told the Palestinian members present, “You’re here by mistake, it’s a mistake that Ben-Gurion [founding father of Israel] didn’t finish the job and throw you out in 1948.”

Yet there is hope. On July 23rd, thousands of Israelis, many of them carrying sacks of flour, marched through Tel Aviv “bearing placards with inscriptions like ‘Starvation is a War Crime.” That the peace movement is starting to stir again can only be a good sign. May it spread!

Especially as follower of Jesus, who believes in the redemptive power of his cross and resurrection, I can pray with faith for healing and peace, not just for individuals, but also for wounded nations and peoples. The cycle of violence and abuse can be broken. Let’s not give in to despair, but work together for peace—for both nations.

After two cataclysmic world wars, over fifty nations gathered in San Francisco in April 1945 to create a new international organization, known as “the United Nations.” After two months of hard work, the UN Charter was written, which specifically called for the formation of three main bodies: a General Assembly, a Security Council, and an Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). It was ECOSOC that mandated a committee to draft a document that would clearly define the notion of human rights, spell them out, and then serve as a basis for future work to establish a body of international law.

Three years later, the text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the General Assembly, with 48 members voting yes and none opposing it—though eight nations abstained. The very first paragraph of the UN Charter had been honored:

We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom . . .

The concept of international law goes back to treaties between nations of the ancient Middle East, but as a legal system, the idea was first developed by the Romans. Still, the notion of a world system consisting of sovereign states working together on some common rules and norms didn’t appear until the European Renaissance. Yet these discussions were mostly limited to questions of war, non-belligerence, and peace. Today’s concept of international law, as seen from the above quote, begins with the idea of human rights, “the dignity and worth of the human person,” which extends to “nations large or small,” and covers questions of justice and mutual respect along with a global effort to expand human flourishing. This was the great push for international development when decolonization was happening in real time.

What is known as the International Bill of Human Rights comprises the 1948 UDHR and the two treaties or covenants adopted by the UN General Assembly in December 1966, the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Nations that have ratified these covenants are obliged to respect, protect, and fulfill these individual rights. Examples of negative rights would be that the State may not torture you or force a particular job on you; or stop people, businesses or political parties from using hate speech against you or your group. Examples of positive rights would be that the State holds private firms accountable to pay their employees a fair wage for their work and to pay men and women the same salary for the same work. Maybe one reason nations like the United States never ratified the ICESCR, is that it stipulates that the State “must provide budgets to make sure everyone can access medicines” and be able to afford decent housing.

The Swiss businessman Henri Dunant personally witnessed the carnage of the 1859 Battle of Solferino in Italy, which led him to found the International Red Cross and rally people behind a conference to draw up rules for modern war. This became the first Geneva Convention (1864), “for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field.” Another Geneva Convention in 1929 dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war, but all of this was updated and expanded in the 1949 Geneva Conventions ratified by 196 nations. It includes four conventions (treatment of the wounded; the victims of maritime warfare; treatment of prisoners; and for the first time, the treatment of civilians in wartime).

You may be wondering how all of this connects to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. After the May 14, 1948 Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, a shaky coalition of fighters from Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon decided to invade. Deeply divided among themselves and distrustful of the Palestinian leadership, they were defeated by the Israelis in the matter of months. The resulting armistice agreements of 1949 allowed Israel to hold most of the British Mandate territory, while Egypt took over the administration of Gaza and Jordan that of the West Bank.

When hostilities heated up again with its Arab neighbors, Israel preempted their attack in June 1967 and won a decisive victory in 6 days (hence, “The Six-Day War” from their perspective). This time, Israel decided to hold on to Gaza and the West Bank and the small territory belonging to Syria, the Golan Heights. Then on November 22 of that year, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 242, calling on the Israelis to withdraw from these territories they now occupied militarily. Six years later, after the so-called Yom Kippur War (the Arabs attacked by surprise on the Jewish Day of Atonement, or Yom Kippur), which Israel nearly lost, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 338, calling Israel to withdraw from those territories a second time.

Significantly, Resolution 242 asserted “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war and the need to work for a just and lasting peace in which every State in the area can live in security.” Besides scores of resolutions over the years by the UN General Assembly and the UN Human Rights Council condemning Israel’s actions in the Occupied Territories (this was not possible in the UN Security Council, as the US routinely vetoes any resolution condemning Israel), the General Assembly adopted a resolution drafted by the Palestinians in September 2024, calling on Israel to end “its unlawful presence in Occupied Palestinian Territory” within 12 months. It passed with 124 votes in favor, 14 against, and 43 abstentions. This means almost two-thirds of the world’s nations favor a two-state solution to this ongoing crisis.

But it is not just continued military occupation that contravenes international law in the case of Israel (57 years so far), it’s also the transfer of its own population into that territory—this Amnesty International page provides a useful summary on the issue of Israeli settlements. In particular, it cites Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” It also prohibits the “individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory.” The list of human rights violations and actions by the Israeli military that routinely breach international law on this page is breathtaking. We lived as a family in the West Bank for three years in the 1990s and I can attest as an eye witness to many of these indignities done to Palestinians. And these have only intensified and multiplied over the years.

But the barbarity of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) in the current war in Gaza goes beyond anything all of us could have imagined. The atrocities committed by Hamas on October 7th, 2023, cannot justify in any way the collective punishment of a whole population by continuous bombing of civilian areas and dozens of forced transfers in various parts of Gaza since that day. Close to 90 percent of Gaza’s buildings have been reduced to rubble—rubble that covers up thousands and thousands of bodies yet uncounted.

But there is more. Prof. Boyd Van Dijk, an Oxford University professor and author of Preparing for War: The Making of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, wrote a piece in Foreign Affairs in April 2025, entitled “Israel, Gaza, and the Starvation Weapon.” Writing as I do at the end of July 2025, the international community as a whole is increasingly outraged by pictures of starving children and adults in Gaza. Most of the 140 who died of starvation so far (88 of those children), have died in the last two weeks. One third of the population is in the fifth stage of starvation, the last stage before death. How can one not conclude that this massive, unfolding wave of starvation is precisely the intent of the occupier? Even the American State Department has concluded that there is no validity in the Israeli allegation that Hamas is stealing the aid from its people.

Yet already in November 2024, the International Criminal Court (established by the 1998 Rome Statute) “issued international arrest warrants not only for the leaders of Hamas but also for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant for war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

Why? The prosecutor, Karim Khan, accuses them of a rarely invoked war crime, mentioned in the Rome Statute as including “intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare” and in particular, by “willfully impeding relief supplies.” The total blockade of Gaza since March, apart from just a trickle of aid at seemingly random points by an aid organization set up exclusively by Israel and the US, while IDF soldiers shoot at them (over a thousand killed so far), has led to massive starvation that worsens every day.

One small ray of hope today: because of the international outcry, the IDF says it will stop its attacks for several hours in different areas every day and let more international aid come in. But you cannot blame this Gazan journalist’s disbelief. Mohammed Mohisen posted this today: “Gaza is drowning in aid in the media. On the ground, starvation endures.” Why?

In my next post, I will show that the dehumanizing of Palestinians and a violent campaign to terrorize them and drive them out formed an integral part of the Zionist plan, almost from the beginning. Just as I have written with candor in this blog about our American genocide of the native population in our country and our shameful treatment of the Africans we brutally enslaved and then oppressed through Jim Crow laws, and, despite the Civil Rights Act, continue to discriminate against by allowing a network of systemic racism to stand—I believe we must speak the truth if we want to see justice, peace and reconciliation to happen. And thankfully, many Israeli historians and activists today are speaking out.

My last blog post dates back to February 2024—over 16 months ago. I had put off long enough serious work on my latest book project, The City Where All May Flourish: The Holy Spirit in Mission and Global Governance. That manuscript was accepted for inclusion in a Brill Publishing series, “Theology and Mission in Global Christianity,” and the review process has begun. To know more about this project, have a look at my article coming out this month in the Missiology journal (also available in Resources).

Here I begin a series of shorter posts on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and my primary concern is to show that the brutally systematic crushing of the Gazan population (2.3 million) in the current war against Gaza following Hamas’s horrendous attack on Oct. 7, 2023 (close to 60,000 killed so far—men, women and children; their forceable displacement multiple times; the destruction of their homes, medical infrastructure and most all of their food sources) is part of a longstanding Israeli plan to “erase” the Palestinian people living in the Occupied Territories (Gaza and the West Bank), either by forcing them to emigrate to various other nations, or by subjugating them to such an extent that they acquiesce to their second-class, colonial identity.

In this first post, I simply make the point that the dehumanization of Palestinians goes back at least to the 19th century, long before the founding of the Israeli state in 1948.

About a year ago, Adam Yaghi contributed a piece to Religion Dispatches, in which he contends that “the desire to annihilate Gaza wasn’t born on 10/7” (the day in 2023 that Hamas launched its horrendous attack on the Israeli communities just outside of Gaza). You begin to see this dehumanization of Palestinians if you read some of the 19th-century travel logs, the most famous of which was Mark Twain’s 1869 650-page book, The Innocents Abroad, Or, The New Pilgrims’ Progress (Subtitle: Being Some Account of the Steamship Quaker City's Pleasure Excursion to Europe and the Holy Land: with Descriptions of Countries, Nations, Incidents, and Adventures as They Appeared to the Author).

Part of Twain’s humorous satire was directed at Catholic, Orthodox, and Muslim Palestinians, something he could easy to get away with, since most of the “pilgrims” (Christians going on a Holy Land pilgrimage) accompanying him on this luxurious cruise were Protestant. Here’s how Yaghi describes Twain’s take on them:

“Though espousing a secular worldview, Twain paradoxically presented Palestinians as morally and spiritually corrupt, and therefore dispensable. The holy city of Jerusalem—symptomatic of the rest of multifaith Palestine—he imagined as ‘mournful, and dreary, and lifeless.’”

Setting the tone for much subsequent literature on Palestine, Mark Twain’s secular eye only noticed a land that, as Yagi puts it, was either “underdeveloped or empty.” For Twain, “Palestinians, portrayed as silent heathens or indigenous savages who hinder progress, had to go.” Indeed, this was “a land infested with marauding Bedouins, overtaken by disease, superstition and poverty.” In Twain’s words, “a thankless and impassive race.” Then he takes an Islamophobic jab, stating that even men with shaved heads would be “careful to leave a lock of hair for the Prophet to take hold of” because “a good Mohammedan would consider himself doomed to stay with the damned forever if he were to [die without it].”

Yet there is an even more troubling dynamic at work here—and you might have noticed it in the above expression “indigenous savages.” Twain intentionally connects indigenous Americans to the native population of Palestine, and thereby betrays his cultural and ideological roots. “Manifest destiny” and the American genocidal settler colonialism that almost annihilated the native American population are the lens through which Mark Twain reads the Palestinian context he very superficially witnessed in a week or two. He is writing this, it turns out, just as American “dime novels” were becoming popular in the United States. In their first incarnation in the 1860s these ultra cheap novels under 100 pages were all about American Indians and their way of life, but their treatment was just as cartoonish as his description of Palestinians life:

“In portraying Palestinians as stereotyped Indians, scalping and whooping on horseback, Twain was equating indigenous people in Palestine and the Americas. The colonial solution to both was implied. In the absence of effective stewardship, colonial logic dictated that only Euro-American settlers could transform this unsettled land into a paradise. Indigenous Palestinians were unworthy of it and should be eliminated or displaced, just like the Native Americans to which this discourse compared them.”

Yet Twain’s racist humor and colonial ideology didn’t stop with his writings. It was eagerly picked up by advocates of a much more powerful 19th-century ideology: Christian Zionism, which in due course helped to produce Jewish Zionism. American and British Protestants of the time were largely influenced by a new reading of the Bible called “dispensationalism,” that is, the dividing up of sacred history into different eras (or dispensations), each one marking a different way God chose to deal with his people. In this scheme, the return of Christ is imminent, putting an end to the current dispensation of God dealing primarily with the church. When Christ returns, he will set up his 1,000-year reign in Jerusalem. This means that Christians have a mandate to make sure the Jewish people return to the land of ancient Israel!

Adam Yaghi mentions two British writers whose books on Palestine were written about fifty years apart, with similar titles and with similar Christian Zionist tropes:

“Palestine was, according to Stewart, the ‘land of the Patriarchs,’ ‘the Prophets,’ ‘the Sacred Poets,’ ‘the Apostles,’ and ‘David and Solomon.’ Palestine was not the land of the ‘Moslem hordes from the desert,’ Stewart argued, or the property of ‘the Arabs or their successors [read: Palestinians], and co-religionists, the Turks.’ The message was simple: under nomadic Palestinian and corrupt Ottoman Islam, Palestine fell to ruins, but it will prosper in the hands of Euro-American Christians who will restore it by establishing a settler-colonial Jewish presence. Stewart’s geography of Ottoman Palestine Judaized the land and erased Palestinian belonging all in service of the Western Christian colonialist project.”

That old dream of blotting out the Palestinians from this Western-supported Jewish colony of Israel is seemingly unfolding before our eyes, Yaghi says. In the next installment I will touch on a theme central to my current book—the founding of the United Nations, the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the emergence of international law.

An article I wrote in 2023 is finally seeing the light of day, or getting published, as the case may be. I had delivered a paper at a joint conference of the Evangelical Missiology Society and the International Society for Frontier Missiology in October 2022 (read it here). That was my second draft of thoughts I had entertained for three years at that point. The first draft was a book proposal written to the main editor (Prof. Kirsteen Kim) of the series, "Theology and Mission in Global Christianity," at Brill Publishing (Leiden, The Netherlands) already in 2019. Her answer was a tentative green light ("Let's have a look at it when you've finished").

It all started at the end of 2018 and the beginning of the next year. Protests were exploding in many parts of the world and spilling out into the streets as people aired their grievances about economic hardship, but most of all about the lack of government transparency and oppressive policies enacted without any regard for their own wishes and demands. In other words, they were witnessing a rise in autocracy. Pictures of crowded protests and brutal police repression filled the pages of the news media reporting on places like Hong Kong, Chile, France (the yellow vests), Sudan, Iraq and Lebanon, and more. [see my blog post of March 2020 on this, and my 2-part series on the massive protests in Algeria where I lived for nine years in the 1970s and 1980s ("Algeria and the Postcolonial Straightjacked"; "Algeria: The Hirak Phenomenon").

Was God the Holy Spirit stirring the hearts of people and, building on deep aspirations instilled in them at creation, was he pushing the needle toward greater democracy? In terms of political theology, is there a connection between human flourishing, good governance, and the values of God's Kingdom as announced and lived out by Jesus Christ -- values to be fully implemented in the New Jerusalem that one day will come down from heaven? The last two chapters of the Bible describe the nations of the world pouring into that city and contributing their own unique gifts for the well-being of all in this completely renewed creation of God, where tears, sorrow, disease and death are no more, and where God takes up residence for the first time.

This article lays out the main themes of the book, which is now being reviewed and should be published in 2026 (The City Where All May Flourish: The Holy Spirit in Mission and Global Governance). The article's title is "Mission and Global Governance: Convergence of Pneumatology and Human Flourishing."

This is a keynote address I delivered virtually at a conference on Faith and the Environment sponsored by the Oxford Centre for Muslim and Christian Studies, March 1, 2024. My title is "Is the Human Vicegerency Bad Theology in the Anthropocene?" The term "vicegerency" is a bit archaic, but it is the word used most often in Muslim academic circles for the "human caliphate" mentioned in several places in the Qur'an, referring to God's creating humankind as deputies or trustees over his creation. The Genesis 1 creation account has God deputizing humanity in this way as well: filling the earth and ruling over it (v. 28). This was a central theme of my 2010 book, Earth, Empire and Sacred Text: Muslims and Christians as Trustees of Creation.

The contemporary Fair Trade concept dates back to British Quakers networking with some social activists and Oxford University academics to found the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief in 1942. The next year this group incorporated as Oxfam with a driving passion to eradicate poverty everywhere. After the war, the Mennonite Central Committee and the Church of the Brethren found ways to help internally displaced refugees in Europe after WWII by collecting and selling their handicrafts. All three initiatives have endured until today: Oxfam, Ten Thousand Villages and SERRV.

One of the main Fair Trade certifying agencies is Fairtrade International. They define “Fairtrade” as “a global system that connects farmers and workers from developing countries with consumers and businesses across the world to change trade for the better.” Watch their very short video explaining what Fair Trade is. Economic justice and equity are its hallmark, as it aims to break the oppressive power differential between North and South inherited from the colonial era.

How does it work? Small farmers or artisans are encouraged to organize themselves into cooperatives. The buyer guarantees a minimum price regardless of market fluctuations (especially important for coffee and cocoa) and adds a social premium, up to 10 percent, for them to reinvest either in the business or their collective well-being (digging wells, building schools, clinics, cotton or rice mills, etc.). Often, the buyer will offer advance credit before harvest time and in all cases seeks to develop a long-term relationship built on trust, respect, and transparency. This is clearly an “alternative trading organization,” as it used to be called. It’s definitely NOT how multinational corporations deal with small coffee or cocoa growers!

I will come back to the Divine Chocolate company later, but here’s a story on their website about one cocoa farmer, Moriba Sama, from an isolated Sierra Leone province with only one town of 1,000 people. The rest of the population is spread out in small villages without clean water or toilets. He describes a democratic process in which the farmers came together and decided how they wanted to spend their Fair Trade premium. They agreed that the priority had to be the water and plumbing infrastructure; then, “working with development partners to provide scholarships” so that their children can at least get through primary school; building a communal rice mill; and finally, establishing a central market in town.

But Fair Trade for me isn’t just an academic or a worthy cause I read about. I’m actually involved in it. Read about my experience at the first “Fair Trade Towns and Universities National Conference” in Philadelphia (2011); my assessment of the Fair Trade movement in 2014; and a local seminar I did on “Why as a Christian I Support Fair Trade.” I could have also, just as easily, taught on why people of faith in general all support Fair Trade.

Bruce Crowther’s Not in My Lifetime: A Fairtrade Campaigner’s Journal

Reading this book was a deeply personal experience for me. I met Bruce in his 2015 visit to our quaint little town of Media, PA (the Delaware County seat on the outskirts of Philadelphia), and I’ve heard so much about him ever since I joined Media’s Fair Trade committee in 2008 (see our latest newsletter here). That was two years after Media declared itself “America’s First Fair Trade Town.” This was only possible because Bruce himself established the first Fair Trade Town ever in 2000 (Garstang, in Lancashire, UK) and went on to found the Fair Trade Towns movement. Our local connection to Bruce Crowther (b. 1959) was through the late Hal Taussig who generously used the proceeds from his alternative touring company in Media (Untours) to establish relations with coffee growers in Mexico. Then he heard about Bruce.

As a result, a Fair Trade committee was established in Media: a good number of shops in town agreed to sell some Fair Trade products; some restaurants agreed to use those products and community organizations (like schools) began to serve coffee, sugar, bananas and more – all products with a Fair Trade label. And finally, the borough council voted to promote Fair Trade in the community and declared Media a Fair Trade town.

To be honest, though, let me say from experience that our job of educating the community about Fair Trade and encouraging businesses, restaurants and shops to buy and use Fair Trade products is never done. It’s all about patient, creative, and determined advocacy, and especially about regular visits to local businesses (it works best in twos). It requires building relationships and finding ways to enhance their bottom line. It’s also about motivating consumers to do use their buying power to lift the less fortunate out of poverty.

Bruce Crowther’s experience over a decade in Garstang was like taking two steps forward and then a step back, several times. It’s definitely a story of perseverance. His book, in fact, while documenting the astounding accomplishments of this campaign (there are now over 2,000 Fair Trade Towns in 34 countries in all six continents today!), also points out several sources of discouragement along the way. Crowther recounts all this in candid detail.

Bruce is also very open about his own struggle with depression and how after nearly dying he benefited so much from one excellent therapist. What also stands out in all the stories leading up to his actual involvement with Fair Trade, is his outgoing personality. Bruce is a leader who easily makes friends, and partly for that reason, he always loved to travel. Like many youths in the 1970s, he traveled on the cheap in Latin America and South Asia. That cultural curiosity and sensitivity would serve him well years later.

And by the way, Bruce has a title to his name in British society. It’s Bruce Crowther MBE, meaning that in 2009 Queen Elizabeth gave him the medal of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his services with Oxfam and the FairTrade Foundation, and Prime Minister Gordon Brown named him one of the “Everyday Heroes” in his book of that name. Yet those honors, clearly, never went to his head.

Among the many fascinating aspects of Bruce Crowther’s story, I will focus here on his vision to tie economic injustice today to the slave trade, and his creation of a bridge between Garstang, New Koforidua (Ghana), and Media, USA, aiming to bring some redemption and healing to the nefarious Atlantic slave trade triangle from the 16th to the 19th century in those same areas.

The Healing Triangle

Bruce qualified as a veterinarian in 1985 and worked for six months in Northern Ireland the next year. This is where he rolled up his sleeves and founded a new chapter of Oxfam – the Dungannon Oxfam Group. He soon moved back to the mainland and successively worked with a veterinary clinic near Lancaster and then one near Liverpool. In 1991, he left his home there to move in with Jane, his fiancée, in Garstang (about 40 miles from Liverpool). They were married the next year. Soon after his arrival in Garstang, he got to know the Methodist preacher, Peter Haywood, who was passionate about eliminating poverty in the developing world and had set up a fair trade shop called the Mustard Seed. Crowther asked him if he would join with him in starting a chapter of Oxfam in Garstang. Haywood was enthusiastic, and soon the Garstang Oxfam Group (GOG) was born.

The year 1994 proved crucial. Apartheid was dismantled in South Africa and the very first Fair Trade certification label, Fairtrade International, started in the Netherlands in 1987, came to the UK. The first products with that new label they could sell in Garstang were Clipper tea, Cafedirect instant coffee, and Maya Gold chocolate. One of the first GOG projects was “to donate a large catering pack of Cafedirect instant coffee to each of the five churches in Garstang” (p. 62). With Jane’s insistence, they added one more Christian congregation, the Quaker meeting house. That was a great idea, as it turned out. At the special meeting to inaugurate the Fair Trade coffee and tea, after Bruce made his short speech explaining what this meant, the clerk of the Meeting, Rachel Rogers, responded, “You’re knocking on an open door.” Rachel was to become one of Bruce’s most influential and ardent supporters and “a major player in Garstang’s declaration as a Fairtrade Town four years later.”

That anecdote is also worth recounting because Bruce, who up to this time had not been “religious” (in the sense that, if there was a God out there, he would sit back and wait for him or her to step into his life and show him the way), it was in Garstang that he gradually found his “spiritual home” in the Quaker meetinghouse at 36 (pp. 62-78). He felt God’s presence during worship, sometimes very strongly, and he loved that these people were very tolerant: one should look for the light of God in every human being. Finally, their values aligned with his: “Becoming a Quaker confirmed my beliefs and strengthened my resolve to see an end to poverty as we know it, once for all” (p. 77).

Quakers were the initiators and for several generations the main drivers of the abolitionist movement in Britain. Bryn Mawr College, one of the three Quaker-founded colleges on the west side of Philadelphia, houses a collection of documents on the Quakers’ role in that movement. Bruce Crowther in 1999 was looking for a hero of the abolitionist movement that had some ties to Lancashire (the most famous one, the parliamentarian William Wilberforce hailed from south Yorkshire). He was on this quest for two reasons. The first was that Oxfam that year was highlighting the Fair Trade Divine chocolate company that was part-owned by the cocoa farmers in New Koforidua, Ghana and a shop in Garstang was now selling it. The second reason was that though Liverpool, Bristol and London had been the biggest slave-trading ports, nearby Lancaster had also gained most of its wealth from that sordid trade.

After some digging, Bruce discovered that the Anglican Thomas Clarkson, “considered by many to be the architect and founding father of the anti-slavery movement” (p. 103), though from Cambridgeshire, built a cottage in Lancashire’s lovely Lake District and spent a good deal of time there. Ah, that counted, said Bruce! He also discovered other commonalities between Fair Trade and past slave-trade abolition campaigns. The latter were unique as a mass political movement opposing a specific social ill. He found an Oxfam article that compared the abolitionist badge “Am I not a man but a brother to you?” with the white band thousands of campaigners wore in Nelson Mandela’s international “Make Poverty History” campaign in 2005.

Thomas Clarkson’s grassroots campaign took him all over the British Isles at the time. One year he even covered 7,000 miles on horseback to gather signatures for his petition. His campaign also included a trade element, albeit a boycott. At the time, “Britain consumed more sugar than the rest of Europe put together.” And yet, West-Indian sugar was grown by slaves. And therefore, people had the power to confront this morally evil trade by refusing to buy sugar. This turned out to be a potent instrument to pressure Parliament to outlaw slavery (p. 104). The Fair Trade campaign is also about the ethics of trade, but with a different emphasis: choose to buy fairly traded products. Of course, in so doing people also choose not to buy products that don’t have the ethical label they can trust. [To see how far the UK has gone in this direction, read this 2016 BBC article explaining the pros and cons of Britain’s best-known chocolate brand, Cadbury, abandoning the Fairtrade label for its own in-house ethical label. As it turns out, Cadbury ended up doing even more to benefit the cocoa farmers and their communities in a sustainable way].

These connections between the slave trade and the 21st-century trade justice campaign are what finally sent Bruce to Ghana in 2001. Representing the GOG, he partnered with the Youth and Community Centre and in the end, twelve people traveled together for three weeks, including five high-school students, part of a youth theatre group. A grant enabled them to perform their play (“Hidden Brutality,” touching on Fair Trade, the Atlantic slave trade, and child labor) in front of several thousand Ghanaian students in several locations. They also visited a Ghanaian charity for children in need in the capital city, Accra, and then the two slave forts on the coast. They visited the cocoa farming cooperative in New Koforidua (Kuapa Kokoo) and had the chance to see for themselves what cocoa farming entails and how it relates to Fair Trade. Finally, they visited the Volta River Estates Limited (VREL) cooperative farm, which at the time, was the only Fair Trade banana plantation in Africa.

This first experience in Ghana opened up a very fruitful partnership with the leaders of Kuapa Kokoo over the years, and this in at least three important ways. The first fruit of Bruce’s personal connection with the chocolate farmers in New Koforidua, Ghana, is the Fair Trade and Slave Trade exhibition. It started small after returning from that first trip in 2001 and was exhibited for several years in the Garstang library and gradually expanded. Then in 2009, Christina Longden of the Lorna Young Foundation (another Fair Trade-minded organization) approached Bruce with the idea of opening the first Fair Trade Center, which would also be a coffee shop selling Fair Trade coffee, tea and chocolate, and house that exhibition about Fair Trade and the transatlantic slave trade. They named it The Fig Tree. The township gave them a suitable location with a four-year lease. It moved to Lancaster in 2015 housed by the historic church of St. John’s. That location allowed them to put together a play that highlighted some of the dynamics between the Quaker abolitionists and the few wealthy Quakers like Dodshon Foster who owned slaves. Much of the Fig Tree’s educational program, already in the Garstang area, consisted in “heritage workshops” on this theme in local schools, so the new location helped them to widen their appeal to the youth and adults of that city.

The second fruit of that partnership with New Koforidua was to expand it to the Americas where by far most of the slaves were shipped like cargo. Hence, the slave trade triangle. In October 2005, after speaking about Fair Trade Towns at a Fair Trade conference in Chicago sponsored by the American FT labeling agency, Transfair USA, Bruce soon got a phone call from Elizabeth Killough who worked for Hal Taussig at Untours and asking him how Media could become a Fair Trade Town. Those discussions led to Media’s self-declaration as the first Fair Trade Town in the Americas (p. 137). Other towns would follow suit, including cities like Chicago, San Francisco and Boston. So now, the healing triangle, that three-fold connection for the purpose of bringing at least some measure of healing to the injustices and indignities of the past, had seen the light of day.

The third fruit of that connection between Garstang/Lancaster and New Koforidua in Ghana was that Bruce learned from them on one of his early visits there (the book mentions seven!) to make his own chocolate from the Kuapa Kokoo chocolate beans. [See the pictures and video which are part of Sabeena Ahmed’s blog post about her visit to the Fig Tree, including making chocolate with Bruce]. First, they have to be roasted, then they have to be ground into a chocolate liquor and then smoothed out into a nice, thick liquid. Then comes the addition of sugar and cocoa butter. Over time, Bruce and his friends developed many different flavors and versions of their “Bean to Bar Chocolate” (click on that tab at the top of the Fig Tree website). Bruce is still making this chocolate, though only selling smaller quantities (he works full-time for the Office of National Statistics) and sending the proceeds to the Fig Tree, of which he is now only one of several volunteers.

Where we go from here

Bruce Crowther ends his book in 2020, when, because of the Covid pandemic, the Fair Trade Towns’ Annual General Meeting was convened online. But it enabled more people to attend: “A total of 37 people from 16 countries joined the link at one time or another.” Then he adds, “a very fitting celebration for a movement made up of over 2,000 Fair Trade Towns across 34 countries.” True, the 14th International Fair Trade Towns meeting in Quito, Ecuador was canceled due to the pandemic, but the movement continues. In fact, with the international protests that year after the killing of George Floyd and the rising visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement, Bruce writes that their “work linking Fair Trade to the abolition of the slave trade and its legacy of racism was more appropriate than ever” (p. 228).

I’ll sign off with the last paragraph in the book—well, almost: a 2-page epilogue follows. Here Bruce connects the end of Apartheid in South Africa with the global anti-poverty campaign by the United Nations via the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Its first goal is “to end poverty in all its forms everywhere” by 2030. The Fair Trade movement in all its diversity is only one very small player in this global campaign. But we all must do our part. Notice that the book’s title are its last four words:

I remain optimistic, however. In my earliest campaigning days when Oxfam was accused by the Charity Commission of taking a political stance by calling for a boycott of South African products, I was certain that we would see an end to Apartheid in South Africa. But I did not believe I would happen in my lifetime. Even if we do not reach the UN target of ending world poverty by 2030, I am just as certain today that, like Apartheid, it will eventually come to an end, albeit perhaps not in my lifetime” (p. 231).

This is an article that I submitted to the academic journal Missiology. After the first round of peer reviews, the editor said they were interested in the article, but some changes needed to be made. I am still waiting to hear back from them about the second draft I sent which took account of the advice proffered. Yet whether this article is actually published by them or by some other journal, I wanted it to be available to those with an interest in these topics. In any case, missiology (the academic study of Christian mission), pneumatology (the branch of theology that studies the Holy Spirit), and global governance, are prominent themes running through the book project I am working on at the present.

The full title is "Mission and Global Governance: A Convergence of Pneumatology and Human Flourishing."

One of the great German theologians of the twentieth century, Jürgen Moltmann (b. 1926), published a book in 2019 that neatly summarizes some key themes of his monumental work: The Spirit of Hope: Theology for a World in Peril. His 1965 (German edition) groundbreaking book had been on Christian hope: A Theology of Hope. Then among his numerous books, at least four are devoted to the Holy Spirit and creation.

This blog post follows the two-part one on “Learning from Indigenous Creation Theology.” I’m digging deeper on the issue of God’s good creation, but my main concern is about the divine role of the Holy Spirit in creation, as well as in human society and history.

Moltmann’s 2019 The Spirit of Hope (at age 95 he released another one, Resurrected to Eternal Life: On Dying and Rising) focuses on the multiple crises facing 21-century humanity and how Christians can respond. In this work published by the World Council of Churches (WCC), his second chapter deals with creation: “The Hope of the Earth: The Ecological Future of Modern Theology.” He begins the chapter with this thought:

“Today we stand at the end of the modern age and at what has to be the beginning of the ecological future of our world, if our world is to survive. . . . The modern age was determined by the human seizure of power over nature and its forces. These conquests and usurpations of nature have now come up against their limits. All the signs suggest that the climate of the earth is changing drastically as a result of human influence. The icecaps of the poles are melting, the water level is rising, islands are disappearing, droughts are on the increase, the deserts are spreading, and so forth. We know all that, be we are not acting according to what we know” (15).

Hence, we urgently need to rethink our traditional (and modern) theology. The Renaissance scholar Pico della Mirandola argued in his classic 1486 text On the Dignity of the Human Being that the world is subject to a predetermined body of laws and that humankind, at its center, is free to study it and exploit its riches. The Bible’s first chapter teaches that human hegemony over nature is justified by their creation in the image of God, but Francis Bacon turned that idea on its head: “human beings rule over nature proves that they are the image of God” (18). René Descartes added that humanity’s rational capacity legitimately reduces nature to mathematical and scientific exploration. This is because in modern theology, “the human being as God’s image is God’s deputy and representative on earth” (19).

Yet, retorts Moltmann, before we humans assume any such responsibilities, we must acknowledge that it’s the earth that cares for us, and not the other way around. Think about it: “The earth can live without us, but we cannot live without the earth” (16). What is more, “God did not breathe the divine Spirit into the human being alone, but into all God’s creatures” (19). The author of Psalm 104 asserts that it was “in wisdom” that God made all his creatures. They all depend on him “to give them food as they need it” (v. 27). Their very lives – literally, their “breath” is in his hands:

“When you supply [their food], they gather it.

You open your hand to feed them,

and they are richly supplied.

But if you turn away from them, they panic.

When you take away their breath,

they die and turn again to dust.

When you give them their breath

[or, “when you send your Spirit”]

life is created,

and you renew the face of the earth” (Ps. 104:28-30).

“Spirit” in Hebrew is ruah, meaning both breath (or wind) and spirit. Both translations of that phrase in the last verse are possible. Certainly, in the many places where in the Old Testament (or “Hebrew Bible”) you find references to the divine “spirit,” Christians see the Holy Spirit, while Jews or Muslims (rouh appears 21 times in the Qur’an, and 4 times with the adjective “holy”) simply see “God’s spirit” as part of who God is. The same could be said for Genesis 2 (often referred to as the second creation narrative): “Then God formed the man from the dust of the ground. He breathed the breath of life into the man’s nostrils, and the man became a living person” (v. 7). This is similar to the Qur’an: “Then he moulded him; He breathed from His Spirit into him” (Q. 32:9; 15:29; 38:72). Also, three times we read that God breathed his Spirit into Mary’s womb, affirming Jesus’ virgin birth: “We breathed into her from Our Spirit and made her and her son a sign for all people” (Q. 21:91; see also Q. 19:17 and 66:12).

In Psalm 51, where David confesses to God his great sin of taking another man’s wife and having her husband killed, he confesses it and asks for God’s forgiveness. He goes on, “Purify me from my sins, and I will be clean; wash me, and I will be whiter than snow. . . . Do not banish me from your presence, and don’t take your Holy Spirit from me” (Ps. 51:7, 11). That is from a Christian translation, the New Living Translation. But the literal Hebrew has it as “don’t take your spirit of holiness from me” – the same idea, but of course, without any Trinitarian content.

The same goes for the second verse of the Bible: “The earth was formless and empty, and darkness covered the deep waters. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the surface of the waters” (Genesis 1:2). For Jews (and Muslims), God’s Spirit is symbolized by a wind and for all three Abrahamic traditions, and sometimes fire (think of John the Baptist: “[Jesus] will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire). The next verse is fitting: “Then God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light” (Gen. 1:3). There certainly was no Trinitarian intent by the human author (that would be an anachronism), but a Christian reading this understands “spirit” as the Holy Spirit, the third person of the Godhead, equal to the Father and Son and indivisible from them, though distinguishable from them by his particular function.

For Christians, trying to discern the identity and role of the Holy Spirit from the biblical texts, and much more, is the branch of theology called “pneumatology” (“pneuma” being the Greek equivalent to ruah in Hebrew). Moltmann has explored the Trinity in a number of his books, but more than any other peer, he has particularly focused on the Holy Spirit, notably in his 1991 book, The Spirit of Life, which he released in anticipation of the seventh Assembly of the WCC in Canberra, Australia, that year under the theme, “Come, Holy Spirit, renew the whole creation.”

In The Spirit of Hope, he offers this comment on the above quote from Psalm 104: “We can deduce from this that if the character of human beings as image of God is due to the Holy Spirit which dwells in them, then all created beings in which God’s Spirit dwells are God’s image and much be respected accordingly” (19). Then he adds, “At all events, human beings are so closely connected with nature that they share in the same distress and in their common hope for redemption. Men and women will not be redeemed from transience and death from this earth, but together with the earth” (19). He then quotes the Apostle Paul:

“But with eager hope, the creation looks forward to the day when it will join God’s children in glorious freedom from death and decay. For we know that all creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. And we believers also groan, even though we have the Holy Spirit within us as a foretaste of future glory, for we long for our bodies to be released from sin and suffering” (Romans 8:19-23, NLT).

In Moltmann’s words, “The Spirit who is now present is the beginning of the new creation, in which death will be no more, for it is the Spirit of Jesus’ resurrection and the comprehensive presence of the risen one.” He then makes an important nod to the Orthodox church tradition: “Orthodox theology has expressed this in the hope not only for the deification of humanity but for the deification of the cosmos too” (20).

For Moltmann, then, we should all be working together, people of all nations, Christians with people of other faiths and no faith, to mitigate the worst of climate change, but also to redress the many injustices of the past and those still being committed today. Peace only comes when justice is addressed. That said, we know that none of this will be achieved before the return of Christ when all – humanity and the whole world – will be renewed:

“The divine Spirit who indwells all things is the present bridge between creation in the beginning and the kingdom of glory. For that reason, the essential thing at present is to perceive in all things, and in all the complexes [sic] and interactions of life, the driving forces of God’s Spirit, and to sense in our own hearts the yearning of the Spirit for the eternal life of the future world” (29).

The Holy Spirit works in individuals and human society for greater justice and peace

The Indian Jesuit theologian Samuel Rayan (1920-2019) has been a dear companion to me in this book project. His 1978 book, The Holy Spirit: Heart of the Gospel and Christian Hope (sadly, out of print) is a good complement to Tinker’s book on American Indian Liberation. Commenting on the second verse in the Bible, Rayan writes, “The whole of creation took place under the presidency of the hovering Spirit of God. When God’s Spirit brooded over the waters, chaos changed into cosmos” (2-3).

What is cosmos? It is “something ordered, beautiful” and it’s what the Spirit brings: “The Spirit can likewise effect this change in human hearts. The confusion, the chaos, the lack of beauty in our hearts can be transformed into a world of order, beauty, and peace.” On the heels of the flood that overwhelmed the world, killing all the life in its path, God the Spirit renewed the earth through the animals and plants in Noah’s Ark, for the Spirit brings life. He also works through human history.

For Rayan, the Holy Spirit is involved in every new movement for the good, and supremely for the work of redemption through Jesus Christ. As he is baptized by John, the Holy Spirit comes upon Jesus in the form of a dove: “As he emerged from the waters, heaven was torn open before him and God accepted him; You are my Son” (7). The Spirit then sent him into the desert to be tempted and tested; “in the power of the Spirit he returned to Galilee; in the power of the Spirit he went to the synagogue at Nazareth,” where he read from the prophet Isaiah:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

For he has anointed me to bring Good News to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim that captives will be released,

that the blind will see,

that the oppressed will be set free,

and that the time of the Lord’s favor has come” (Luke 4:18-19; Isaiah 61:1, NLT).

Rayan explains, “From the moment of the baptism the Spirit took charge of the ministry of Jesus, of his life, of his world. What Jesus spoke thereafter was what the Father revealed to him and communicated to him through and in the Spirit. The deeds he did were henceforth regulated, determined, made meaningful through the Spirit. The wonders he worked, the signs, the miracles, all were done in and through the Spirit, and it was the Spirit that revealed their divine meaning to the disciples (John 16:13)” (8). Then at Pentecost, as Jesus had promised his disciples before his crucifixion, resurrection and ascension, the Holy Spirit came with great power on the first group of Christians assembled for prayer in Jerusalem. The coming of the Spirit “meant total nonconformity to everything that was opposed to the will of God and the willingness to pay for this nonconformity. . . . After Pentecost, the disciples were willing to pay the price because they were strengthened and illuminated by a new Power, the power of the Spirit” (8-9).

But notice how he widens the scope of the Spirit’s action – way beyond the confines of the church: “The Spirit is associated with all great beginnings. He is the Initiator of fresh developments and the Leader of new movements. He is alive at every turning point in the march of life on earth. He is the Creator Spirit” (9). This is not traditional theology. Even the Orthodox, who have given the Spirit the greatest role and attention, would not venture to say, like Rayan does, that sociopolitical movements that have led to liberation for the oppressed, like those led by Gandhi in India and Martin Luther King, Jr. in the United States, had in their sails the wind of God’s Spirit.

Rayan challenges us to listen to the Spirit as we contemplate current events, partly because God’s Good News, inevitably, has political implications:

“Coming to our own times we should ask if the Spirit is not at work in the many movements that characterize our world today. In this century how many lands that were once in the grip of colonial powers have striven for independence. The first great struggle, the struggle of India, has been followed by the collapse of practically the entire colonial system. Where is the God of Exodus and the Spirit of freedom at work?” (131).

At the same time, he is not naïve. We need discernment and reflect about the extent to which a movement reflects “the values for which Jesus lived.” Those values include “human dignity, greatness, freedom, wholeness.” But human life is always tainted by sin: “In this earthly life of ours the brightest light has a touch of darkness; our greatest holiness is somehow touched with selfishness” (133).

My interest in bringing the Holy Spirit into this project of human flourishing and global governance started in 2019 when I was struck with the outpouring of political protests, often very risky, in places as diverse as Hong Kong, Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, France, Chile, and elsewhere too. What drives people into the streets, sometimes at great personal cost? I did write a blog post about this, right as the pandemic shut down the world as we knew it. I explained the many different issues involved in each case, and though I didn’t mention anything about God’s Spirit, it was certainly on my mind. Any movement that strives towards greater “humanization,” as Rayan puts it, is a call to bring about justice for the downtrodden and dignity to the oppressed. It is also a cry of the heart, a prayer deep inside the human soul, perhaps even unconsciously, for the coming of a New Earth where justice, peace, and love will reign supreme in God’s presence.

Liberation theology with an evangelical flavor

Rayan’s book was published in 1978. Six years later, thirty-seven evangelical missiologists (theologians specialized in mission theology) from the Global South came together in Tlayacapan, Mexico, to sharpen their understanding of what God was doing in the world and how he was calling his people to be involved. Their conference published a Declaration at its closing, but not in English. Noted Honduran missiologist C. René Padilla contributed the last chapter to a 2016 edited book, The Spirit over the Earth: Pneumatology in the Majority World. Commenting on Latin American pneumatology in particular, Padilla notes that it seeks to uncover the practical ways the Holy Spirit guides his people in their everyday challenges, and “especially in the context of poverty and oppression” (165). Whereas Western Protestant pneumatology limits its focus on the church and personal salvation and sanctification, the perspective is much broader in Latin America. If the sphere of the Spirit’s action is confined to the church, then social issues are worldly matters Christians need not worry about. But he disagrees: “If, on the contrary, the intermediary God is present in creation and history, all issues that affect human beings, regardless of race, sex, or socioeconomic status in the present world, become a matter of Christian concern” (169). He then offers an English translation of a passage in the Tlayacapan Declaration:

“The Spirit’s creative work can be seen in all the spheres of life – social, political, economic, cultural, biological, and religious. It can be seen in anything that awakens sensitivity to the needs of people – a sensitivity that builds more just and peaceful communities and societies and that makes possible for people to live with more freedom to make responsible choices for the sake of a more abundant life” (169).

It goes on to explain that the mission of the church includes joining the work of the Holy Spirit who is promoting, among other things, environmental sustainability and the kind of activism we would label today “global governance”:

“It can be seen in anything that leads people to sacrifice on behalf of the common good and for the ecological wellbeing of the Earth; to opt for the poor, the ostracized, and the oppressed, by living in solidarity with them for the sake of their uplift and liberation; and to build love relationships and institutions that reflect the values of the Kingdom of God. These are ‘life sacraments’ that glorify God and are made possible only by the power of the Holy Spirit (169-170).

Padilla marvels that these African, Asian, and Latin American Christian theologians mentioned “the ecological wellbeing of the Earth” at a time when evangelicals generally ignored such issues. And yet those concerns have only become more acute, to the point that “the very survival of Planet Earth is under threat” (170). First, he quotes from Pope Francis’ first encyclical (2015), Laudate Si: On Care for Our Common Home (see my blog post on it, part I and part II). Then he cites Anglican missiologist John V. Taylor who delivered the Cadbury Lectures at the University of Birmingham in 1967. Taylor later reworked those lectures into a book, The Go-Between God. This excerpt of that book Padilla offers is a nice conclusion to this post. Taylor is reminding us that part of our collective mission is to follow the Holy Spirit’s lead in caring for creation – both listening and responding to “the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor,” as Pope Francis put it:

“The Spirit of God is ever at work in nature, in history and in human living, and wherever there is a flagging or corruption or self-destruction of God’s handiwork, he is present to renew and energize and create once again. Whenever faith in the Holy Spirit is strong, creation and redemption are seen as one continuous process” (171).

In the first half of this post, I introduced Native American theologian George E. “Tink” Tinker and used some of the material in his book, American Indian Liberation, to offer us a double reality check: first, the horrors committed by the colonial masters in the Americas, starting with Columbus and stretching the United States’ genocide of the Native populations in the name of Manifest Destiny. The History channel offers a helpful page on this shameful past: “Broken Treaties with Native American Tribes: A Timeline.” From the Revolutionary War and the aftermath of the Civil War (1778-1871), the U.S. government and Indian nations signed 368 treaties. All were broken.

The second reality check is that the 3-4 million who identify as members of indigenous nations are the poorest and most vulnerable demographic in the USA. Tinker wrote that “we are damaged goods,” still reeling psychologically, socially, economically and spiritually from their colonizer’s abuse in all these areas. Add to that the church’s complicity in the oppression of the Indian peoples and the destruction of their way of life. Christian leaders have (consciously or unconsciously) subscribed to a heretical doctrine of White supremacy and colonialism. Christians in the pews, knowingly or not, have imbibed the settler worldview of their White culture. When President Andrew Jackson pushed through Congress the Indian Removal Act of 1828 which set in motion the horrific suffering of hundreds of thousands of tribal peoples during the Trail of Tears, where there any churches that spoke out against it? Very few did. But too, when Christian engaged in missionizing Indian reservations, with all the best intentions in the world, they often contributed to the breakdown of these Native’s cultural safeguards and their psychosocial equilibrium by preaching a Jesus that looked too much like themseves. Here is how Tinker puts it:

“We live with the ongoing stigma of defeated peoples who have endured genocide, the intentional dismantling of cultural values, forced confinement on less desirable lands called ‘reservations,’ intentionally nurtured dependency on the federal government, and conversion by missionaries who imposed a new culture on us as readily as they preached the gospel” (42).

The Clash of Worldviews

Tinker elucidates the contrast between “euro-western” culture (which informed much of Christian theology over the centuries, and especially since the Protestant Reformation) and the indigenous cultures. For him, there are “four fundamental, deep structure cultural differences between Indian people and the cultures that derive from european traditions” (7):

1. Indigenous traditions are spatially rooted, as opposed to Western ones which are temporarily rooted; “history and temporality reign supreme in the euro-west, where time is money and ‘development,’ or progress, is the goal” (7). The worldview of indigenous peoples revolves around their land and all its components, whether living or inanimate (not a word in the Indian vocabulary).

2. Whereas euro-westerners prioritize the individual and his or her rights, Native peoples are “communitarian by nature.” He explains, “Thus, for instance, [for Indians] spiritual involvement in the ceremonial life of a community is typically engaged in ‘for the sake of the people’ and not for the sake of individual salvation or personal spiritual benefit. This continues to create deep anxiety and rifts in the minds and hearts of Native Americans who have embraced Christianity, for example, and if you add the heavy burden of the church’s past complicity in the suffering of their people, you begin to understand why many Native Christians are leaving behind their Christian faith and devoting their spiritual energies to the ceremonial life and rituals of their Native tradition (though many practice both simultaneously).

3. For indigenous peoples, everything in the natural or created world is organically related. Whereas euro-western people see themselves as distinct and above the natural world – and therefore free to exploit it as they choose, in Indian cultures people “live and experience themselves as part of creation” (8). Think of Disney’s film, The Lion King, and the theme song, “Circle of life.” Their wider community includes “animals (four-legged), birds, and all the living, moving things (including rocks, hills, trees, rivers, and so on), along with all the other sorts of two-leggeds (e.g., bears, humans of different colors) in the world” (9).

4. Native peoples have “a firm sense of group filial attachment to particular places that comes with a responsibility to relate to the land in those places with responsibility” (9). That is why the eviction of Native Americans from their tribal lands remains so traumatic to them. Another consequence of that tribal attachment is that land ownership itself, whether individual or even group ownership, is completely foreign to their worldview.

What Native Americans can teach us

Tinker is right: “Perhaps the most precious gift that American Indians have to share with amer-europeans is our perspective on the interrelatedness of all creation and our deep sense of relationship to the land in particular. . . . Just as there is no category of the inanimate, there can be no conception of anything in the created world that does not share in the sacredness infused in the act of creation” (10). Creation is the theological bedrock of indigenous communities and the circle is the commanding metaphor: “Our prayers are most often said with the community assembled in the form of a circle” (48). It is as if the circle represents the tribe’s connection to other tribes and to all humans, and then to all the universe in creation. Hierarchy is absent from this worldview. Chiefs are chosen by consensus and they are called to embody the collective will of the tribe. Kings and kingdoms are puzzling concepts to them. Put otherwise, the indigenous worldview is egalitarian – their relatives are animals and all elements of the physical world created by God, or the Great Spirit, or some similar conception, depending on the tribe. They also believe in many spirits associated with all manifestations of creation; hence, the overarching concern in this theology of creation is the call to harmony and balance.

This idea is so important that all tribes believe that in order to respect “the established boundaries,” specific ceremonies must be performed if any act of violence is necessary (like killing an animal for food or cutting down a tree for building a sweat lodge). Tinker explains, “Acts of violence against any relative disrupt the balance and are inexcusable.” The same applies to war:

“Likewise, most tribes engaged in elaborate ceremonies before going to war with another tribe. Even one’s enemies must be respected. No killing was to be random. A tribe’s survival or territorial integrity might be at risk. Nevertheless, maintaining balance, respect for all one’s relatives, meant that four to twelve days of ceremony might be necessary before battle could be engaged” (55).

Along with respect, the American Indian would add “reciprocity” to the central dynamic of our human interaction with the land and all its creature. Just as “prayers and the offering of tobacco are reciprocal acts of giving something back to the earth and to all of creation in order to maintain balance,” the Osages and other plains Indian peoples performed specific ceremonies before engaging in a hunt and the killing of buffaloes. Indeed, they “lived a close sibling relationship with the buffalo.” These ceremonies, then, were seen as “necessary to restore life to the buffalo nation” (40). Tragically, he asks, “what do we return to the earth when we clear-cut a forest or gouge out a strip mine leaving miles upon miles of earth totally bare?”

Yet if our Christian theology truly started with God creating the heavens and the earth as in the early church’s ecumenical creeds (e.g., the Nicene Creed), then we would also realize that all human beings are equally sacred by virtue of creation. So the question comes, “Where is the reciprocity, the maintaining of cosmic balance, with respect to those who are suffering varieties of oppression in our modern world? Blacks in southern Africa, non-Jews in Palestine, Tamils in Sri Lanka, or tribal people in Latin America?” (41).

Liberation theology is a Third-World thing

Even though the Vatican has condemned the Marxist-inspired “liberation theology” distilled in the writings and activism of Latin American theologians like Gustavo Gutiérrez and others, official Catholic social doctrine teaches that God’s “preferential option for the poor” is central to the gospel. Reading the words of Jesus and following him through the four written gospels makes that abundantly clear. But is this what Tinker is referring to in his title: American Indian Liberation? In fact, he is not. That phrasing, he insists, “is nearly meaningless language for Indians” (136). To identify “the poor” in that way is to refer to a modern socioeconomic structure in which different classes compete for power in a capitalist economic system. It also presumes an individualistic view of personhood. By contrast, affirms Tinker, “Indian people want affirmation . . . as national communities with discrete cultures, discrete languages, discrete value systems, and our own governments and territories” (136). Human rights are still relevant, but in a different way. Indigenous peoples have been recognized as the “Fourth World,” and the landmark United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted by the General Assembly in 2007.

Just a quick footnote here. Article 26:1 of that Declaration states, “Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.” Let me inject a small note of hope here. The U.S. government’s Advisory Council on Historic Preservation just posted a lengthy article, “Announcement of US Support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Rights.” When the said UN Declaration was presented to the General Assembly in September 2007, the United States was not one of the 143 nations to sign it. President Obama changed that in 2010. The article explains,

“U.S. support for the Declaration goes hand in hand with the U.S. commitment to address the consequences of a history in which, as President Obama recognized, ‘few have been marginalized and ignored by Washington for as long as Native Americans – our First Americans. That commitment is reflected in the many policies and programs that are being implemented by U.S. agencies in response to concerns raised by Native Americans, including poverty, unemployment, environmental degradation, health care gaps, violent crime and discrimination.”

The article documents a number of discussions, decisions and the earmarking of several billion dollars in land acquisition and other measures to improve the lives of Native Americans. Our current Secretary of the Interior is a Native woman, Deb Haaland, and more work is being done in this area. [Read also about how the State of Minnesota just decided to return a state park to a small tribe adjacent to it – a first in the U.S., partly because of its Indian burial site and mostly because of a massacre perpetrated there in 1862].

Tinker’s creation theology