-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

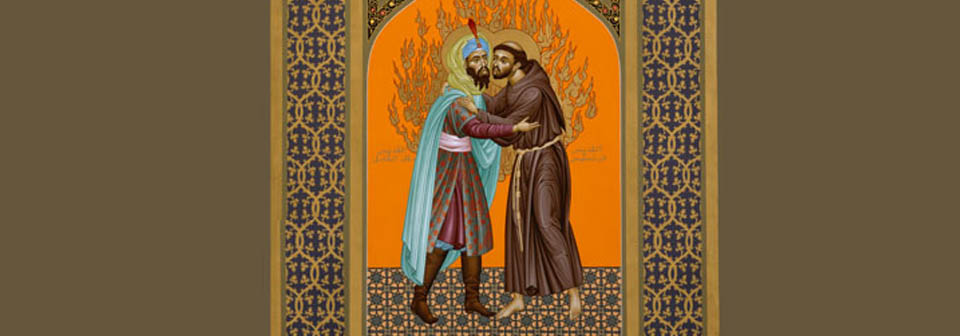

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

Modern day slavery is on the rise. In the 2014 UN Global Report on Trafficking in Persons (just published at this link) we read about the following tragic trends:

Sexual exploitation of children, I hope we can all agree, is the vilest form of cruelty to our fellow human beings. And as the report lays out in great detail, no part of the world is spared from this plague and women bear the brunt of this tragedy. I touched on some of this in a series of three blogs in 2012 under the title of “Religion and Patriarchy” in the category of “religion and human rights.” But so much more should be said, especially when you realize that every year over 12 million persons, with more and more of them now being children, are abducted and enslaved.

Note too that the percentage of trafficked persons used for forced labor is on the increase. We know, at least anecdotally, that many children are sold by parents who are too poor to care for their many children, and girls in particular. We also hear about young women hiring themselves out as maids to wealthier families in other parts of the world and being badly exploited in slave-like conditions. It could be in the United States or Europe, but even more likely in countries like in the Arabian Gulf area where laws and their enforcement are particularly lax. Here’s an article about Indonesian maids being treated as “modern day slaves” in Hong Kong.

All this to say that the International Organization for Migration (IOM) figure of 21 million is very likely just the tip of the global trafficking iceberg. In the official statement announcing the release of the Report on Trafficking of Persons, Yury Fedotov, the executive director of the UN Office of Drugs and Crime, wanted to emphasize that the statistics told only part of the story. “It is clear that the scale of modern-day slavery is far worse,” he wrote.

We're talking about the poorest of the poor here – those robbed of their basic human rights, stripped of all dignity and at the total mercy of their captors. But not far behind are the more than ten million internally displaced persons (IDPs) who are now under the care of the UN Refugee agency (UNHCR). They have become IDPs through war and natural disasters. But just as many more people are being trafficked than simply those who can be counted, there are many more people suffering from famine and war than those directly managed by the UNHCR.

That there is often a direct link between the trafficking of persons and poverty is a point made by a respected NGO specialized in this work, the Institute for Trafficked, Exploited & Missing Persons (ITEMP). They point to the 2009 US State Department Trafficking in Human Persons report. Here is how a short article on their homepage frames the issue:

"By comparing gross domestic product information with source/destination information provided in the State Department’s 2009 Trafficking in Persons report, ITEMP personnel discovered a strong correlation between a country’s per capita GDP and their odds of being a source or destination country for international human trafficking.

Every $1000 increase in a country’s GDP makes the country nearly 10 percent more likely to be a destination for international human trafficking victims.

Likewise, every reduction of $1000 in a country’s GDP makes the country 12 percent more likely to be a source for international human trafficking victims.

‘By finding the roots of the problem, we can begin to look for permanent solutions,’ ITEMP Director of Operations Charles Moore said."

In the first blog we used stories and figures from the IOM to look at one aspect of that growing gap between rich and poor globally. We saw that the estimated 800,000 migrants who yearly entrust their escape from either crushing poverty or political instability to unscrupulous smugglers are only a small part of the total picture.

We discovered that, despite the spike in violence and political unrest in the Middle East, most migrants are motivated by the desire to provide financially for their families. Poverty is at the root of these mass migrations today.

And what is more, beyond the millions of refugees and persons trafficked, we learned that 21 percent of the world’s population lives in “extreme poverty” (living on less than $1.25 a day). That’s roughly 1.4 billion of our fellow human beings.

Poverty and the unequal distribution of resources – including basic necessities like food and shelter, but also access to safe water, good schools, electricity, health care, and more – is actually worsening in some of the developing countries (including the US), says the World Bank in a short “Poverty Overview.”

Lessons from growing inequality in the US

So the issues of modern-day slavery, the plight of the refugees and the “extreme poor” remind us that we live in a world plagued by inequality. But as an American citizen, I am also reminded of the fact that at home too the gap between haves and have-nots has grown wider in the last few decades.

Google’s chief economist Hal Varian teamed up with the New York Times' Upshot on a research project in the summer of 2014 seeking to correlate particular searches on the web with the easiest and the toughest places to live in the US. This was based on previous research that had demarcated these areas on the basis of six factors including life expectancy, education and income.

David Leonhardt explains that searches with the highest correlation to the poorest US counties (mostly in Kentucky, Arkansas, Maine, New Mexico and Oregon) covered the following interests and concerns:

“. . . health problems, weight-loss diets, guns, video games and religion are all common seach topics. The dark side of religion is of special interest: Antichrist has the second-highest correlation with the hardest places, and searches containing ‘hell’ and ‘rapture’ also make the top 10.”

By contrast, “In the easiest places to live, the Canon Elph and other digital cameras dominate the top of the correlation list. Apparently, people in places where life seems good, including Nebraska, Iowa, Wyoming and much of the large metropolitan areas of the Northeast and West Coast, want to record their lives in images.”

For Leonhardt this project shows that “[t]he rise of inequality over the last four decades has created two very different Americas, and life is a lot harder in one of them.” He explains,

“Income has stagnated in working-class communities, which helps explain why ‘selling avon’ and ‘social security checks’ correlate with the hardest places from our index. Inequality in health and life expectancy has grown over the same time. And searches on diabetes, lupus, blood pressure, 1,500-calorie diets and ‘ssi disability’ – a reference to the federal benefits program for workers with health problems – also make the list. Guns, meanwhile, are in part a cultural preference, but they are also a health risk.”

George Packer, a staff writer at the New Yorker, delivered the 2011 Joanna Jackson Goldman Memorial Lecture on American Civilization and Government at the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for Scholars & Writers. It was entitled, “Inequality and Social Decline in America” (later published in Foreign Affairs Magazine). The nub of the issue is this, he writes:

“The persistence of this trend toward greater inequality over the past 30 years suggests a kind of feedback loop that cannot be broken by the usual political means. The more wealth accumulates in a few hands at the top, the more influence and favor the well-connected rich acquire, which makes it easier for them and their political allies to cast off restraint without paying a social price. That, in turn, frees them up to amass more money, until cause and effect become impossible to distinguish.”

Growing inequality, the result of this trend, “leaves the rich with so much money that they can binge on speculation, and leaves the middle class without enough money to buy the things they think they deserve, which leads them to borrow and go into debt." This was certainly one of the causes of the 2008 Great Recession and it “hardens society into a class system, imprisoning people in the circumstances of their birth – a rebuke to the very idea of the American dream.”

Two years later, President Obama put it in terms of upward mobility, or in this case, the lack thereof:

“The problem is that alongside increased inequality, we’ve seen diminished levels of upward mobility in recent years. A child born in the top 20 percent has about a 2-in-3 chance of staying at or near the top. A child born into the bottom 20 percent has a less than 1-in-20 shot at making it to the top. He’s 10 times likelier to stay where he is. In fact, statistics show not only that our levels of income inequality rank near countries like Jamaica and Argentina, but that it is harder today for a child born here in America to improve her station in life than it is for children in most of our wealthy allies – countries like Canada or Germany or France. They have greater mobility than we do, not less.”

This issue of inequality has loomed so large in our political and social discourse that the New York Times ran a series on the topic for a year and a half. It was moderated by Nobel-Prize in economics laureate Joseph Stiglitz (2001), who, in the closing article of the series (“Inequality Is Not Inevitable”) called the United States “the advanced country with the greatest level of inequality.”

I will come back to him, but first some figures from a study that was published this month. Henry Gass describes the project: “The study, from Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley and Gabriel Zucman of the London School of Economics, uses a greater variety of sources to paint its picture of wealth inequality in the US than other recent analyses.” Here are some highlights:

Back to Stiglitz. C.E.O.s make on average 295 times more than the typical worker, he says. This is an “ersatz capitalism”: our response to the Great Recession that struck late in 2007 was to “socialize losses and privatize gains.” That is, tax payers paid the bills, while the super wealthy pocketed millions more. No one was indicted and much less imprisoned for years of shady gambling on national wealth (my take on it). But this is no inevitable trend, he argues:

“If it is not the inexorable laws of economics that have led to America’s great divide, what is it? The straightforward answer: our policies and our politics. People get tired of hearing about Scandinavian success stories, but the fact of the matter is that Sweden, Finland and Norway have all succeeded in having about as much or faster growth in per capita incomes than the United States and with far greater equality.”

What is more, Stiglitz isn’t shy about laying bare the causes and manifestations of this rising inequality. In part he blames the bankers and corporate heads who in their passionate push for laissez-faire economics (less regulation, please!) nevertheless have welcomed the series of bail-outs that have characterized the era inaugurated by Reagan and Thatcher. Moreover, this economic privilege is undergirded by political privilege. In other words, “The American political system is overrun by money. Economic inequality translates into political inequality, and political inequality yields increasing economic inequality.” As a result, almost a quarter of children under five in America are poor.

Poverty and political powerlessness also correlate with a restricted access to justice. Reeling as we are with the fallout of a black eighteen-year-old gunned down by a white policeman in Ferguson, MI, we know that our justice system as a whole is broken. As Stiglitz puts it, the contrast between the two Americas couldn’t be greater:

“Where justice is concerned, there is also a yawning divide. In the eyes of the rest of the world and a significant part of its own population, mass incarceration has come to define America — a country, it bears repeating, with about 5 percent of the world’s population but around a fourth of the world’s prisoners.

Justice has become a commodity, affordable to only a few. While Wall Street executives used their high-retainer lawyers to ensure that their ranks were not held accountable for the misdeeds that the crisis in 2008 so graphically revealed, the banks abused our legal system to foreclose on mortgages and evict people, some of whom did not even owe money.”

Theology does matter

In the first blog I wrote that inequality worldwide was a human rights issue, thus both moral and theological. If God created us all – each and everyone of us – in his image, calling us to be his representatives on earth, his khulafa’ or trustees over his creation, we should not tolerate the fact that millions of us are trafficked for sex or greed, or struggling to find food to feed their families, or forced out of their land by wars and then drowned in the sea by greedy smugglers or left to die of thirst under the scorching Texas sun.

According to the Qur’an,

“We ordained for the Children of Israel that if anyone killed a person not in retaliation of murder, or (and) to spread mischief in the land - it would be as if he killed all mankind, and if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all mankind” (Q. 5:32)

This verse closely parallels some discussions in the Talmud, as I showed in one of my earliest blogs, “‘My Brother’s Keeper’ as Human Solidarity.” In the same vein, but more along the lines of poverty, we read in Deuteronomy, “Cursed be anyone who deprives the alien, the orphan, and the widow of justice” (Deut. 27:19 NRSV). Then this from Isaiah the prophet, “Learn to do good. Seek justice. Help the oppressed. Defend the cause of orphans. Fight the right of widows” (Is. 1:17 NLT).

Inequality to some extent is natural. Each human being is born with abilities and disabilities, and within a specific family, class and cultural context. Yet the kind of inequality we have been examining in these two blogs is egregious and an insult to the Creator.

There is a lot people of faith can do – yes, and people of compassion and human decency of all stripes – both locally and globally to reduce inequalities and contribute to human flourishing among those suffering the most. It involves both charitable ventures and political advocacy. In fact, instead of rivalries, misunderstandings, and polemics between religious traditions, let’s compete in good works; and better yet, let’s link arms, pool our strengths and get to work.

“Each community has its own direction to which it turns: race to do good deeds and wherever you are, God will bring you together. God has power to do everything” (Qur’an 2:148, Abdel Haleem translation).

In a twist of events one could hardly imagine in a horror film, a boat owned by smugglers deliberately destroyed their human cargo. They rammed into a rickety boat jammed with four or five hundred migrants (who had paid them a minimum of $2000), capsizing it instantly. Over one hundred children and many more adults perished in the instants that followed. And as the boat circled around them, the smugglers laughed sadistically.

Despite their cruelty, over one hundred managed to cling to various objects. They then locked arms to keep warm in the cold sea a hundred miles or so from the island of Malta, but most slipped under the waves as the hours turned into a day and then to almost four days. The handful who survived had resorted to drinking their own urine and struggled with hallucinations.

One of the survivors was picked up by the Pegasus, a ship that had just rescued 386 other migrants from another shipwreck. According to the survivors, all Palestinians from Gaza whose houses had been destroyed in the recent war with Israel, there were also migrants from Libya, Eritrea, Sudan and Egypt.

Just that week six other ships brimming with migrants went down. But this case was different. As the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein (a Jordanian national), declared, these smugglers are likely guilty of “mass murder” and should be brought to justice.

Some grim facts about migrants

A couple of weeks after this particular disaster, the Geneva-based International Organization for Migration (IOM) published a study conducted over six months entitled, “Fatal Journeys: Tracking Lives Lost during Migration.” Here are some of its stark figures:

I could not agree more with IOM’s director-general, William Lacy Swing:

“The paradox is that at a time when one in seven people around the world are migrants, we are seeing an extraordinarily harsh response to migration in the developed world. Limited opportunities for safe and regular migration drive would-be migrants into the hands of smugglers, feeding an unscrupulous trade that threatens the lives of desperate people. We need to put an end to this cycle. Undocumented migrants are not criminals. They are human beings in need of protection and assistance, and deserving respect.”

What’s behind these population flows?

The IOM Regional Director for Europe – which we now know to be the number one destination for migrants – is Bernt Hemingway. In a June 2014 blog he noted two realities dramatically clashing at the moment: the desperation of all of these migrants willing to risk their lives to survive, or at least find a better life, and the shrill and strident voices of condemnation of them in European societies. Those traveling include some of the most vulnerable – women, often pregnant, and children. On the other side, these people are painted as invaders, and even criminals seeking to steal their hard-earned benefits.

“Emotive language colours the landscape with visions of surges, hordes and invasions, and this has been amplified in the various national debates surrounding the EU elections,” notes Hemingway. Yet when you stop to think about it, his starting point is inescapable from a moral standpoint: “But we must understand that for most the situation is desperate, and work from there.”

He then adds, “The complex flows of people across the Mediterranean are a result of conflict, poverty, inequality and the quest to support or protect families when all options are exhausted at home.”

I have to inject here what I just learned and experienced in watching a jarring and gut-wrenching 42-minute documentary about thousands of deaths of migrants in Brooks County, Texas. Entitled “The Real Death Valley”, (improbably) sponsored by the Weather Channel and Telemundo Investigative. I didn’t just cry. I wept. These weren’t just statistics, but real human beings and in particular the story of two brothers marked for killing by gangs in San Salvador.

Brooks County is not on the Texas border. It’s 70 miles north of the Rio Grande river, which the travelers cross with their “coyotes” (smugglers). They are then taken in trucks to just a few miles of a major checkpoint where agents with dogs check for migrants. Then they are guided around the checkpoint by traversing huge private ranches for two or three days. But anyone sick or not able to keep up in the oppressive heat and humidity is simply left behind. Most of those who die fall into this category.

Back to the two brothers. The sick one, now terribly dehydrated, is close to death and the older brother calls 911. The local police, with only one officer at a time able to respond, usually calls the border police who are much better staffed. But sometimes the waiting time is too long, as in the case of this young man who dies after several hours. Fortunately, his brother is saved. I’ll let you watch the film to catch the rest.

Globally, however, war and the breakdown of law and order are not the leading causes of such hazard-laced migrations. In the MENA region (Middle East & North Africa) there is no doubt that the series of uprising in 2011 (optimistically dubbed the “Arab Spring” at the time) have left behind bitter conflict and several million refugees. But that is not the whole picture. Before this and still today, migration is caused by “poverty, inequality and the quest to support or protect families when all options are exhausted at home.”

Hence the topic of inequality I touch on here and in the second hald of this post.

Inequality is a moral and theological issue

Some good news, to start with. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon in May 2013 announced to the General Assembly as he rolled out the 2013 Human Development report that “[w]e are at the beginning of an historic journey.” This report aimed to build on and expand the original Millennium Declaration of 2000 and the ensuing Millennial Development Goals (MDGs) and chart the way forward past the 2015 goal. Ban summarized the objective thus:

“The post-2015 process is a chance to usher in a new era in international development – one that will eradicate extreme poverty and lead us to a world of prosperity, sustainability, equity and dignity for all.”

Growing up as I did in France, the French revolutionary slogan “liberty, equality and fraternity” was drilled into us school children. In the American version, the three “inalienable rights” trumpeted in the Declaration of Independence are “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The latter, I fear, has been reduced with time to economic opportunity. But equality of opportunity was never mentioned and, much less, emphasized. And that’s just at the national level, whereas the Secretary General is speaking about all humanity.

We certainly can rejoice that this 2013 report informs us that the share of extreme poverty in the world has dropped from 43 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2013 and that by 2030 most middle-class people will live in countries no longer considered “poor.” What is more, we can applaud the conclusion of the 25-member panel as to the proposed revision to the MDGs – specifically, “five major transformational shifts”:

That said, we’re still left with the IOM’s yearly figure of 800,000 people trafficked across borders. Grinding poverty still accompanies the daily suffering of a quarter of humanity and leads many to entrust their fate to the wiles of criminal smuggling gangs.

I am in the process of writing (or rewriting “Muslim Theologies of Justice,” as seen on my homepage) what is so far entitled, “Justice and Love: A Muslim-Christian Conversation.” My thesis is that justice – and I mean “primary justice” here – is about human rights. It’s about the basic rights of human beings simply because they are human beings. I started moving in that direction in my article (see it in Resources), “A Muslim and Christian Orientation to Human Rights: Human Dignity and Solidarity” now published in the Indiana International and Comparative Law Review.

All I’ll say here is that the UN body in the three decades following the historic Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was on the right path when it attempted to hammer out a more legally binding version of it in two covenants – the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). The United States is among a few countries that never ratified the ICESCR. Economic rights remain controversial in societies that pride themselves on individualism and the least possible regulation on the exploitation of capital.

The Prophet Muhammad was an orphan and the Qur’an constantly rebukes the rich who callously neglect or especially exploit the poor, the widow and the orphan. That’s why one of the Islam’s five pillars is zakat – the duty to redistribute 2.5 percent of your assets for the benefit of the poor on an annual basis (for more on this, see “Zakat and Poverty Allieviation”).

Jesus was the archetypal migrant, who owned nothing and “had no place to lay his head.” His teaching also reveals that he firmly believed the radical social justice discourse of the Hebrew prophets, as for instance Isaiah’s portrayal of “true fasting”:

“Free those who are wrongly imprisoned . . . Share your food with the hungry, and give shelter to the homeless. Give clothes to those who need them” (Is. 58:6-7 NLT).

Jesus summarized this in the two commandments in the Law of Moses: love God with all your heart, mind and soul; and your neighbor as yourself (see Mark 12:30-31 and parallels).

Solidarity is not only the right attitude to adopt toward fellow human beings in great need. It’s an attitude of love God calls us to put into action. More on this in the second half.

The core of the human rights paradigm is that all human beings by virtue of simply being human are bearers of inalienable rights. The intrinsic dignity of the human person, moreover, is the guarantee of the universality of the international human rights standard. Human dignity also includes human solidarity, as evidenced in international law by the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ratified in 1966. This paper argues from a comparative perspective, therefore, that human rights discourse is reinforced by the central tenets of both Islam and Christianity in two areas, its universality and its application to the economic sphere.

“A Muslim and Christian Orientation to Human Rights: Human Dignity and Solidarity,” Indiana International and Comparative Review 24, 4 (2014): 899-920.

Muslims often say – with a twinge of pride, I’ve noticed – that there is no clergy in Islam. Well, there is no pope and each mosque is fairly independent; that said, the more conservative ones in this country do their best to import a good imam from Egypt or elsewhere. Also, Iran’s constitution calls for the supremacy of the jurist-scholar in running the affairs of state. “Right,” you say, “but those are Shia beliefs.”

Still, Islamic scholars, the kind who teach Islamic sciences and offer legal opinions (fatwas), either as state functionaries in Muslim-majority countries or as members of various Islamic associations in the west, wield a lot of clout. These are the ulama (“those with knowledge”).

So my question is this. With the Mideast in turmoil (and even more than usual!) – mostly because of the so-called “Islamic State,” who really speaks for Islam? Maybe it’s not the ulama but the politicians and statesmen who wield the decisive power to “speak” in these ways.

Saudi Arabia, after decades of funding conservative Salafi causes, including the Salafi-jihadis of Afghanistan in the 1980s and those of various stripes fighting Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria since 2011, has now joined with the Arab Emirates and Egypt to lead an Arab front against ISIS. In so doing, they seek to isolate Qatar, which has always been an ally of the Muslim Brotherhood (which, by the way, has no connection to ISIS; the MBs gave up violence in the 1950s). Turkey, much more powerful than those three combined, is a member of NATO and is on better terms with Qatar, since it is ruled by an islamist party. President Erdogan is leveraging his massive influence to get the US-led coalition to directly turn on Bashar al-Assad as well.

I could go on. But all I’m saying for now is that, just as it has always been in Islamdom, rulers and ulama stand in tension, sharing power uneasily – political power on one side, and religious authority on the other. But first, we need some historical background.

Some remarks about history

As I tell my Introduction to Islam students, the only “real” Islamic state lasted for ten years in Medina with Muhammad at its helm as founder, prophet and statesman. Sure, his four closest Companions continued to rule in Medina for the next 29 years. Yet apart from the great wealth flowing in from the astonishingly successful conquests (and maybe in part because of them), this rule was hardly idyllic. Three of these successors (the “Rightly Guided Caliphs”) were assassinated, with Ali, the last one, embroiled in a civil war from the start. Nineteen years later, the Umayyad caliph Yazid massacred the Prophet’s grandson Hussein, his family and entourage, at Karbala in Iraq. This represents the Shia’s defining moment, when their second “Imam” sacrificed his life in the way of God and for the sake of his followers.

What after Ali’s assassination in 661 constitutes an “Islamic state”? I suppose it’s in the eye of the beholder, but the 20th-century ideology of “islamism,” crafted first and foremost by the Muslim Brotherhood (founded in 1928) and now widespread under many forms, is sure that it did exist, at least in bits and pieces in the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties and the great “Gunpowder States” like the Ottomans, the Safavids (“Greater Persia”) and the Moghuls (India). The islamist slogans from the beginning were “Islam is the solution” and “the Qur’an is our constitution.” The more puritanical Salafis would answer that no genuine Islamic state ever existed after 661. Yet some of them now recognize ISIS as "the real deal."

The problem, of course, is that now we’re talking about a modern nation-state, the product of European Enlightenment ideals and statecraft hammered out in the ashes of Europe’s religious wars. These are states in which power is concentrated in various degrees among the three branches of government, executive, judiciary and legislative.

Islamic states came in many shapes and sizes over the centuries – from the mammoth Abbasid caliphate at its peak in the ninth and tenth centuries, to breakaway petty dynasties on the edges, to the various kingdoms and fiefdoms of West Africa and Indonesia. What they had in common, however, was the tremendous power of the ulama, the jurist-scholars who interpreted and applied God’s law, or the Shari’a.

In his great book The Fall and Rise of the Islamic State, Noah Feldman explains how the ulama, “the heirs of the Prophet,” were the guarantors and mediators of the law which the rulers were sworn to follow. Indeed, caliphs, sultans, and local kings, if they cared at all about Islamic legitimacy, were told by the Qur’an to “command the right and forbid the wrong.” So they had to appoint judges from among the ulama. This also meant that if the ruler wanted to pervert justice for his own gain he would be seen by the ulama as violating God’s law, which immediately disqualified him from ruling in the eyes of the ulama and the people.

In practice, the ulama wielded only moral or religious authority, not military force. So they could hardly strip a sitting ruler of his title. Yet when any strong man seized power, either by force or by being the heir of the deceased, he urgently needed “to be able to rely on the scholars to assert the continuing legitimacy of his rule” (Feldman, 32). There might be several other claimants and challengers. But too, if the country was menaced by a foreign invasion, “the ruler would need the scholars to declare the religious obligation to protect the state in a defensive jihad” (32).

So the history of past “Islamic states” is replete with instances of this tug-of-war between political power and religious authority, between rulers and the ulama class. This fact entailed, ostensibly, a tension between religion and state, if not a de facto separation. Don’t forget too that rulers usually had their own set of courts (mazalim courts) and that a whole branch of jurisprudence gave legitimacy to the ruler’s laws (siyasa shar’iyya). But the sultan or king still needed to appoint ulama to the top courts of his realm. In the end, justice was still God’s justice, emanating from the divine Shari’a.

With the advent of European colonialism, particularly after Napoleon’s short invasion of Egypt in 1798, more and more traditional Islamic states imported western codes of law and consolidated state power at the expense of the ulama. Whether Muhammad Ali in nineteenth-century Egypt or Kemal Attatürk in 1920s Turkey, rulers sidelined and even muzzled the traditional jurist-scholars. In the 1960s, President Gamal Abd al-Nasser simply “nationalized” al-Azhar University in Cairo, in essence putting the ulama under the thumb of the state, something unheard of in Islamic history.

An article for your perusal

In light of this background, I will offer two thoughts on the topic of the ulama and their role today. The first is to call your attention to a chapter of mine (“Yusuf al-Qaradawi’s Purposive Fiqh: Promoting or Demoting the Future Role of the Ulama?”) in the newly published book edited by my friend, Adis Duderija: Maqasid al-Shari’a and Contemporary Muslim Reformist Thought: An Examination. It’s a case study of arguably the most popular of today’s ulama, Shaykh Yusuf al-Qaradawi. Some of you will remember that I’ve published two other chapters in other books on him in the past. You can read another blog of mine that is in part about Qaradawi. Here I argue that his turning to this popular legal methodology of the “objectives of Shari’a” in the late 1990s may actually undermine his overall goal of increasing the influence of the ulama. For more on this, see the pdf document of this chapter in “Resources.”

Ulama and Sultans today

My main interest in this blog, however, is to have you reflect on the current balance between religious authority in Muslim circles and political power. Granted, each of the 57 states with membership in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC, formerly “Organization of the Islamic Conference”) are unique in their political and religious orientations. Also, not all are Muslim-majority nations.

Still, this is the first time since 1924 that an armed group having conquered a vast territory is calling itself a “caliphate.” That was when the secular leader of Turkey officially abolished the Ottoman caliphate. So now, by declaring himself “caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, head of ISIS, is claiming the rightful leadership of the worldwide Islamic umma. Naturally, all manner of condemnations and official recriminations have rained down, and only a couple or so jihadi groups have pledged allegiance to him.

Enter the Ulama. First, British Islamic leaders, both Shia and Sunni, produced a video condemning ISIS as standing against all the central tenets of Islam. Second, and much more significant, a letter of condemnation was presented in a press conference on September 25, 2014, entitled, “Open Letter to al-Baghdadi”. This 23-page document is written by 126 Muslim scholars, most of whom recognized jurists in Islamic law. The whole letter is a point-by-point refutation of the doctrines and practices of ISIS in the language and form of classical Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). Again, scholars are both Shia and Sunni – a self-conscious and deliberate attempt to stigmatize Baghdadi’s virulent sectarianism.

You can download a copy of this letter on a site dedicated to it. From the Executive Summary which opens it, let me just offer you five of the 24 points:

7. It is forbidden in Islam to kill emissaries, ambassadors, and diplomats; hence it is forbidden to kill journalists and aid workers.

8. Jihad in Islam is defensive war. It is not permissible without the right cause, the right purpose and withoutthe right rules of conduct.

9. It is forbidden in Islam to declare people non-Muslim unless he (or she) openly declares disbelief.

10. It is forbidden in Islam to harm or mistreat—in any way—Christians or any ‘People of the Scripture’.

11. It is obligatory to consider Yazidis as People of the Scripture.

All this is abundantly clear. All 24 points – and the legal content of the next 22 pages – represents the consensus of the vast majority of jurist-scholars in the Muslim world today. The above points, I thought, need no commentary, except perhaps the ninth. This is the issue of takfir, or the practice of declaring a fellow Muslim an unbeliever (a kafir, or infidel, or apostate), and therefore, according to classical Islamic law, naming that person a legitimate target for killing. That of course is the crux of all jihadi movements today, as it was in the very first generation of Muslims when the Kharijites (or khawarij) left Ali’s ranks in the Battle of Siffin and waged guerilla warfare against the central Islamic state.

So the ulama still wield influence today (see for example the Fiqh Council of North America and some samples of their recent legal opinions). But their role is much more ambiguous and limited than it was in the premodern period. Apart from the fact that many Muslims are neither very practicing nor conservative enough to pay attention to them, there is another issue that looms large in the background.

The divisive issue of politics – internal and geopolitical

I alluded to this question in the beginning. Saddam Hussein by invading Kuwait in 1990 set off a series of events that have led to the perilous situation we now observe in the wider Mideast. Consider the following:

Much more could be added, but these are the salient points. Now I've saved one last source for you that merits attention.

The 2014-2015 Muslim 500 issue

This year’s issue of “The World’s 500 Most Influential Muslims” just came out (see my 2012 blog, “Defining Power: The 500 Most Influential Muslims”). This sixth edition of the Muslim 500 is the first one that isn’t free (it’s only $4.99 for a low resolution copy) and perhaps the first one that is showing signs of hurried editing (some typos and other mistakes here and there). Still, it’s an impressive publication and, as I mentioned before, it says a great deal about the Jordanian royal family’s (and especially Prince Ghazi’s) theological and political views. It’s also a handy way to check the pulse of traditional Muslim leadership at any particular historical juncture. The editor’s introduction (Abdallah Schleifer) devotes 4 of his 10 pages to the Da’ish phenomenon he calls “a murderous heresy.” “Da’ish” is the Arabic acronym for ISIS, which is used in the Arab world and in France.

Two points stand out here. The first is the prominence of the Open Letter to al-Baghdadi, published in full in this issue. Schleifer connects it to the juridical language of the Amman Message of 2005, which I have described as the most significant Islamic consensus document in over a thousand years. In his words,

“The Amman Message (p 30) which was of groundbreaking importance at the time precisely because it confronted the pretensions of Al-Qaeda and lesser known extremist groups. But the Open Letter is the most comprehensive Islamic juridical rebuttal by orthodox scholars of the “religious” justifications for revolutionary Salafi-jihadis, manifest in its most extreme form by DA’ ISH.”

What Schleifer is affirming here is the pivotal role of the ulama in contemporary Islam in marginalizing the horrific acts and grievous ambitions of militant Islam and the historic efforts put forth by his own patrons, the Jordanian royal family who employ him. And this leads us to the second point.

Schleifer simultaneously castigates Saudi Arabia for using its wealth since the late 1970s to spread its brand of Salafism (Wahhabism) around the world and thereby unwittingly letting the Salafi-jihadi genie out of the bottle. The proof is that ISIL has systematically distributed the works of 18th-century reformer Muhammad bin Abd al-Wahhab in every conquered territory.

With that background in mind, reasons Schleifer, we can breathe a sigh of relief that Saudi Arabia, along with the UAE and Egypt, has firmly condemned Da’ish and all other islamist adventurism. In his own words,

“King Abdullah has also firmly embraced Al-Azhar – the citadel of Orthodox Sunni religious thought and very much targeted by both Salafi groups and the Muslim Brotherhood in the anything-goes environment in Egypt of the Arab Spring and then its transmutation into Muslim Brotherhood rule for one year.”

Notice three things in this statement: 1) a strong affirmation of the importance of the Sunni ulama and their spiritual/theological center in Cairo’s al-Azhar; 2) a political statement: the Arab Spring was a calamity; and 3) President Sisi is a righteous bulwark against the Salafis and the Muslim Brotherhood (two very different phenomena, I’ll add).

So who are the "good" Muslims and who are the most influential? By now, I’m sure you’re dying to know who’s who in this year’s Muslim 500 list. In just the first top 20, eight are heads of state, eleven are ulama, and one is both (Ali Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran – in 3rd place). The only islamist in the first fifty is Khaled Mashal, the leader of Hamas. Just this little bit says a lot!

This leads me to my last remark. Prince Ghazi of Jordan, himself both alim (singular of ulama) and royal family member embodies to perfection the traditional Islamic worldview I have alluded to in this blog. Who calls the shots in Islam today? In this globalized world of the Internet and massive flows of populations, it’s an impossible question to answer. That said, if you mean who is influential in mainstream traditional Islam, the answer is what it has always been – a constantly shifting power ratio of politicians and ulama.

The above title could be said about much of life. As St. Paul writes, “We see through a glass darkly.” Here I want to discuss current events in the Mideast, first in Egypt, and then the issue of the Islamic State. Looking through the eyes of western media outlets and consulting insider sources yield quite a different picture. Consulting the insider views put us in a better position to see how progress can be made and then join others – especially people of faith, Muslims and Christians – to make that happen.

President Sisi’s Egypt

Two points should be made here. First, Sisi’s Egypt is even more authoritarian and repressive than Mubarak’s was. Egyptians haven’t forgotten the “January 25, 2011 Revolution” and it’s just a matter of time before the people rise up again. Second, the military coup that toppled President Morsi in July 2013 was not about secularism versus islamism (spelling it as it is, a political/religious ideology). Those two ideologies are indeed opposed, but their opposition does not come close to explaining the current political dynamics in that country.

Professor Mohamad Elmasry of the University of North Alabama rightly called Sisi’s policy one of “elimination” – but not just of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). I covered the facts about how the army and police in concert massacred about one thousand MB followers (Aug. 14, 2013) in my third blog on the post-coup realities.

Elmasry’s opinion piece came on the heels of the MB leader Mohamed Badie’s death sentence along with 682 of his followers on April 28, 2014. This was after 529 others had received a similar sentence the month before – in spite of Badie’s public words calling his followers to remain peaceful and not to respond to violence in kind. He declared himself ready to die for his own convictions as a peaceful protester.

Though most of the more than 1,500 protesters who were killed in the following months were MB-affiliated or at least sympathizers, some of those were not. Likewise, the 16,000 jailed political opponents since then were not all pro-Morsi activists.

In reality, the post-revolutionary situation of non-Muslim religious groups has not improved under Sisi, as New York Times correspondent David Kirkpatrick attests. “Nothing has really changed,” said Christian Kameel Kamel, whose 26-year-old son had been jailed for blasphemy against Islam and who still hasn’t appeared in court since the appeal to his first sentencing.

The “culture of sectarianism” has continued unabated, asserted human rights activist and researcher Ishak Ibrahim. Yet, amazingly, Christians remain mostly pro-Sisi. As a fellow Christian, I think they will likely come to regret their hatred for the Muslim Brotherhood. Hatred (or even fear) does not become followers of Christ; what is more, there are plenty of other Muslims advocating a greater role for Islam in Egypt (i.e., “islamists”) who don’t like the MBs; finally, when some day greater democracy is restored (as we all pray it will), this could come back to bite their community.

Beyond Christians, there have been two high-profile cases of people imprisoned for atheism, and at least three Shiite Muslims have been condemned to the legal sentence (five years in prison) for blasphemy as well. Religious freedom is badly lacking in today’s Egypt.

Ironically, the 2012 presidential election saw massive numbers at the polls. Morsi won with only a three-percentage-point lead and the electoral process was considered fair by international observers. By contrast, the 2014 election saw little participation, as the outcome seemed inevitable. As a Middle East Report article makes it clear, even with an artificial two-day extension of the voting period, the state’s declared 30 percent participation seemed inflated. The pro-regime media badgered and pressured people to vote with slogans like this, "Any woman who goes shopping instead of voting should be shot or shoot herself." To no avail. Only a few came out to vote.

Also like Mubarak and Sadat before him, Sisi portrays himself as the defender of “true” Islam and has found, as they did, the al-Azhar establishment (perhaps still the most prestigious Islamic university in the world) very obliging and supportive of his cause. For instance, when al-Azhar condemned the recent Noah film as “a clear violation of the principles of Islamic Sharia,” the official state censorship board upheld the ruling. Emad Shahin, a well-know political scientist who left the country in protest of Sisi’s policies (barely escaping his own imprisonment), President Sisi has made “extensive” use of religion to bolster the legitimacy of the “coup leaders.”

Though manipulating religion for political gain is as old as the world, it is likely that Sisi is playing with the same dynamite that blew up Mubarak’s regime (see also Elmasry’s piece, “Egypt’s ‘Secular’ Gov Uses Religion as a Tool of Repression”). The so-called “Islamic Revival” has been transforming Egypt since the late 1970s and shows no signs of abating. The best book to read on this is still journalist/scholar Geneive Abdo’s masterful No God but God: Egypt and the Triumph of Islam.

A veteran liberal opposition leader, Ayman Nour (he ran against Mubarak in 2005 and is now exiled in Lebanon) recently said in an interview that Sisi was a one-sided president. He isn't representing all Egyptians, but only following his own anti-Brotherhood path. In the end, he quipped, "Mubarak took us many years back, and what Sisi is doing will not push us to the front. Sisi's actions will bring us to the abyss."

Just to give you an idea of how serious the human rights situation is, have a look at this article explaining why the Carter Center decided to pull out of Egypt. Jimmy Carter and his advisors believe that "the upcoming [parliamentary] elections are unlikely to advance genuine democratization."

Considering some of his other writings, I was pleasantly surprised by a recent piece by New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, entitled “ISIS and SISI”. Taking his cue from Israeli analyst Orit Perlov, Friedman contends that two governing styles now dominate the Mideast: the radical Islamic ideology of ISIS and the absolute power of the (secular?) state under Egypt’s Sisi. Yet neither “hyper-Islamism” nor “hyper nationalism” will deliver what the people desperately need – “the education, freedom and jobs to realize their full potential and the ability to participate as equal citizens in their political life.”

Friedman is right to label Sisi’s regime as “hyper-nationalism” and so is Elmasry in putting “secular” between quotation marks. Egypt’s top clerics (ulama) and Pope Tawadros II regularly appear on Egyptian TV to sing the regime’s praises and heap blame on the Muslim Brotherhood. Yet, as I said earlier, this is to play with fire, at least with regard to the vast Muslim majority of Egyptians. Sure, Muslims gladly spilled into the streets to call for Morsi’s resignation, but many of them, and not just the ultra-conservative Salafis, yearn for a more authentically “Islamic” regime, as anthropologist Yasmin Moll has discovered in her research on the Egyptian media industry (“Islamism beyond the Muslim Brotherhood”).

Moll’s fieldwork was conducted between 2010 and 2013 among some leading media producers who worked for a “transnational Islamic channel that defined itself primarily against the Salafi television channels that were closed down by the military following the coup.” Most of these “saw themselves not just as muttadayinin (religious) but also as islamiyin (‘Islamists’). Yet, they were highly critical of the Muslim Brotherhood’s year in power, with many of them joining the massive June 30 protests against Morsi.”

This is not how the tensions in Egypt are generally portrayed in our Western media. We usually read that Sisi leads the existential struggle for a secular state against the arrayed forces of militant Islam led by the Muslim Brotherhood. It’s much more complicated than that, writes Moll. In the social milieu in which these producers move, there are no “secular liberal elites.” Rather, these people “explicitly believe that secularism cannot be legitimately justified or reasoned from within an Islamic frame.” She explains,

“This is because, for them, Islam guides and makes normative claims on every aspect of human life, including political life. They were not against the Muslim Brotherhood because of its similar commitment to the “comprehensiveness” (shumuliyyat) of Islam, but because they perceived the organization as arrogant and incompetent, nepotistic and exclusionary. That the Brotherhood claimed to be acting in the name of religion while behaving badly made its actions much worse, but their support for Sisi’s removal of Morsi in no way hinged on seeing the military as a bastion of secularism.”

Unlike the Salafis, however, this islamist orientation involves in some fashion “creating a shared space (masaha mushtarika) between Egyptians of different political orientations and moral sensibilities, including between those who identify themselves as pious and those who do not.” This is not unlike the AKP ruling party of Turkey some call “soft islamism,” which is comfortable functioning under the umbrella of a secular constitution. But above all, it’s about a democratic politics that could be adapted and adjusted for use in a Muslim-majority country like Egypt.

No, things are not what they seem in Egypt from watching the news on mainstream TV or reading about them in Western news outlets. Might the reality look more hopeful from another vantage point? Maybe not. But knowing it in more detail and in a more balanced way politically makes it more interesting. And, who knows, we might be able to influence our lawmakers and politicians to take a more constructive path in relating to this part of the world.

The unhelpful “Islamism” prism

Dennis Ross, a diplomat with a wealth of experience in this region under several US administrations, wrote an OpEd on the heels of President Obama’s speech outlining his strategy to defeat the Islamic State. Unfortunately, Ross takes a manichean view of the Mideast: the islamists versus the non-islamists. The latter are “our friends,” he argues, the others our enemies. But these "friends" also happen to be “the traditional monarchies, authoritarian governments in Egypt and Algeria, and secular reformers who may be small in number but have not disappeared.” We might have worked more closely with Turkey and Qatar, but both these Sunni states support the Muslim Brotherhood.

But this also means, Ross asserts, “recognizing that Egypt is an essential part of the anti-Islamist coalition, and that American military aid should not be withheld because of differences over Egypt’s domestic behavior.” Forget human rights, or at least turn a blind eye to them in light of more pressing issues. Why partner with these “non-Islamists” states? His answer is simple:

“These non-Islamists are America’s natural partners in the region. They favor stability, the free flow of oil and gas, and they oppose terrorism. The forces that threaten us also threaten them.”

Ross had astutely explained why in his opinion the “Arab Awakening” of 2011 had failed to produce democracy in the region. Three reasons:

“The institutions of civil society were too weak; the political culture of winner-take-all too strong; sectarian differences too powerful; and a belief in pluralism too inchoate. Instead, the awakening produced political vacuums and a struggle over identity.”

Still, Ross feels the Obama Administration is too squeamish about “about appearing to give a blank check to authoritarian regimes, when it believes there need to be limits and that these regimes are likely to prove unstable over time.” Obama, like Carter long before him, actually cares about issues of human rights and people having a say in how they are governed (though not enough so, in my opinion). Ross retorts that Egypt and the UAE are already bombing the islamists in neighboring Libya without asking for our permission. Don’t discourage them, he warns, but work with them in the hopes of harnessing this energy in the right direction and more effectively.

My question to Ross is this: isn’t running roughshod over people’s convictions and lending support to regimes (like Egypt and Saudi Arabia) who ignore their people’s basic human rights a bad strategy in the long run? It seems to me that the US already has such a lamentable record in the region for arrogant and blundering interventions that this will just reinforce widespread anti-American feelings among these peoples. If “stability” is just another word for “political repression” – which it is in practice – then this is just as shortsighted as the neo-conservative-inspired 2003 invasion of Iraq.

And ISIS?

What about ISIS, you say? Well, first of all, to get a good feel for its territory on the two rivers see this interactive map. Then read this piece by Shane Harris in Foreign Policy: “Obama’s Mission Impossible”. A New York Times editorial concludes about the same thing, just looking at the challenge of training “moderate” Syrian rebels in the fight against ISIS. The US has a pitiful record when it comes to training troops, whether in Iraq or Afghanistan. And then, these rebels’ only focus is on bringing down the Asad regime. Channeling their energies to effectively fight IS is truly a long shot.

Finally, read the transcript or listen to Terry Gross’s recent interview of the New York Times Baghdad bureau chief Tim Arango on Fresh Air. He details how the US poured $5 billion into training the Iraqi army that simply crumbled when confronted with ISIS and shows how ISIS is the de facto creation of American adventurism in Iraq.

Much more could be said, but let me end with this thought. President Obama likely has no political alternative to pursuing his announced combination of Sunni coalition building and bombing to “degrade” the Islamic State’s military capabilities – though the most logical neighbor with the most goals in common happens to be Iran. Too bad he “can’t go there” (politically)! But we should have learned our lesson by now. Particularly in this part of the world, war is always counterproductive.

Things as they should be

Jim Wallis speaks for many Christians and people of other faiths too when he writes that “War Is Not the Answer”. He reminds his readers that before the 2003 invasion of Iraq US church leaders offered a peaceful alternative that would still meet the stated goals of the war – in six points. In fact, it was seriously discussed in Tony Blair’s cabinet meeting. “The American church leaders’ plan,” the UK Secretary of State Clair Short told Jim Wallis, really was an attractive alternative to war because it showed how Saddam Hussein’s regime could be brought down and his WMD’s dismantled (it turned out they didn’t exist).

I agree with Wallis. The American president should have waited another couple of weeks when the US chairs the UN Security Council meetings in New York. His idea of coalition building is good, but it needs to be widened. Will it take longer with UN involvement? It will, but that’s the only way to recover some legitimacy for its actions in that region and for a much greater amount of pressure globally to be put on the Islamic State for seizing vast territories by force and all the while committing untold crimes against humanity. In the end there will have to be some force applied against IS, but applied on the basis of a wider coalition will more likely empower the local Muslims, both Sunni and Shia, Christians and others, to rally around plans for more transparent, broad-based and efficient governance. That’s the only stability that will last.

It’s time people of faith, and particularly Muslims and Christians, speak out for peace and work together as local and global civil society to see these kinds of goals implemented in the region. Instead of looking at how things seem from the vantage point of the powerful, both insiders and outsiders of the Mideast, they could help each other see how the world should look like – more just, peaceful and compassionate – and find ways to move in that direction.

A couple of weeks ago Duke University Arabic professor Mbaye Bashir Lo attended Friday prayers at the Grand Mosque of Niamey, Niger. Originally from Sudan, he’s doing research on militant Islam in West Africa this summer. What he heard the preacher say startled him: “These are troubling times: there is killing everywhere, and certainly, these are signs of the end of time.” This was followed by a hadith of the Prophet, “At the end of time neither the killer nor the victim will know the reason of the killing.”

Lo’s article that inspired this blog was published in al-Arabiya online, the Saudi/Emirati-owned news service, based in Dubai and al-Jazeera’s closest competitor in the Middle East. [At least at this writing the article has several mistakes, and even one in the title; I’ve never seen that on al-Jazeera!]

One point he makes is that since the 1991 Gulf War (First or Second, depending on whether you count the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s), no war has been fought between two national armies. George H. W. Bush’s international coalition was composed of armies contributed by those nation-states fighting Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi army. But the Balkan wars of the 1990s, for instance, had to do with the breakup of former Yugoslavia. I think he’s right, but if you can think of a counter-example, please post a comment below.

When the US and Britain invaded Iraq in 2003 they quickly routed its army and then followed nine years of fighting mostly Sunni militia, with an increasingly organized al-Qaeda branch on the side. Think too of the Russian “rebels” fighting the central Ukrainian government forces in Donetsk and other eastern provinces. This is a proxy war, with Russia clearly involved, of the same type that has been raging in Syria for three and a half years now.

That said, as Lo recognizes, most of the violent hot spots today involve at least some Islamic militants:

“Look at the news highlights of the past week: a suicide car bombing killed 21 in Baghdad; gunmen killed 21 security forces on Egypt's western border; in Gombe, Nigeria, Boko Haram militants killed 32 villagers in different towns; in Libya, 38 were killed as the Libyan Army and Islamists clashed in Benghazi; in the Chaambi mountains of Tunisia, gunmen killed at least 14 Tunisian soldiers. The list goes on, to say nothing of what is occurring in Syria, Somalia, and Yemen, among other places.”

To say the least, this is depressing and even bewildering for the vast majority of Muslims worldwide. Why is jihadism on the rise, anyway? After all, and by far, Muslims remain the majority victims of this systematic slaughter of civilians.

I want here to discuss Lo’s answer in three parts. First, it seems that militant Islam is feeding on both favorable ideological and geopolitical conditions. Second, as I alluded to above, we might be seeing the “fading of an old order,” that is, the international order the foundation of which go back to Swiss political philosopher Emerich de Vattel’s The Law of Nations is being seriously shaken. And finally, as I’m (slowly) writing my book on justice, I’ll comment on how “justice” might relate to this topic, especially in the way Lo ends his piece.

Jihadism, dying and victory

Lo thought that the imam’s sermon was “very relevant in the current discourse of militant Islam.” Muslims generally believe that the Prophet Muhammad was victorious because he was “right.” In other words, his was a righteous and just cause and so he prevailed religiously, politically and militarily. Lo explains, “There is a right reason and a wrong reason to die. The right reason is associated with victory, while the wrong reason is associated with peril and defeat.”

The converse is that if your cause is unjust, you cannot prevail. That of course posed a cruel dilemma for Muslims under colonial rule. How could these plundering conquerors have the upper hand? The same logic, adds Lo, buoyed ISIS founder (IS from now on, The Islamic State) Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in his bid to break off from al-Qaeda and declare himself caliph of all Muslims. Had he not, unlike Ayman al-Zawahiri, proved his mettle by conquering a territory larger than that of Great Britain? IS fighters took control of a quarter of Iraq while chanting, [We are on] “the righteous path, and the sign is self-evident.”

Sayyid Qutb (executed by President Nasser in 1966) glorified martyrdom (shahada) for martyrdom’s sake, continues Lo (on him, see my blog, “Jihad Revisited”). This mindset prevailed until the Muslim Brotherhood actually came to power in Egypt in 2012. Jihad now is all about achieving victory. Lo continues:

“The new leaders, Al-Baghdadi in Iraq, Muhammad al Zahawi (the leader of Ansaar al-Sharia in Libya), Ramadan A. Shalah, (the military leader of Islamic Jihad in Ghaza,) and Abubakar Shekau (the leader of Boko Haram in Nigeria), are not interested chiefly in shahadah. They want tangible evidence of victory: bondage, ransoms of war, estates and Khilaafah [caliphate]—for them, these are the hallmarks of real power. According to the Yemeni singer Abu Hajir al-Hadrami, through jihad, al-Baghdadi is ‘re-wiring the Muslim land.’”

That's a few words about the ideological vacuum the jihadis have filled. Regarding the favorable geopolitical conditions, I'll only state the obvious: jihadism finds its home in any territory (under)ruled by a weak state and thrives when instability turns to chaos -- like Sudan for bin Laden after Afghanistan, then Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover; then post-US invasion Iraq; then the Syrian civil war and Iraq in the last eight months.

The fading of an order?

Vattel penned The Law of Nations (the French original, “Droit des Gens,” could also be translated “The Right of Peoples”) in 1758 a century after the horrific religious wars known as the Thirty Year War. For me there’s an eerie parallel with today. Sure, nation states were involved in the fighting, but at bottom it was Christians fighting Christians.

Vattel’s central thesis is that only a sovereign can declare a war and only troops can fight troops. Civilians should both stay out of the fray and be protected from harm. Are we witnessing the end of that order? Over 70 percent of the recent Gaza war’s victims were civilians, with almost 500 children killed.

By the way, Vattel’s Swiss editor Charles Dumas sent Benjamin Franklin three copies of the French book just before American independence. Franklin in his letter of thanks included this phrase, “It came to us in good season, when the circumstances of a rising State make it necessary to frequently consult the Law of Nations.”

So is that order passing? Lo might be overstating his case. Vattel’s book fed into the wider current of Enlightenment philosophy that also inspired the US Declaration of Independence and Constitution, the French Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, and eventually the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the body of international law that followed. Should the UN fall apart (heaven forbid!), yes, that would mark the end of the era of international law – contested as it is. But Lo is raising an important issue, that of justice and how it works out on a global scale.

Justice and legal theory

Having published a good amount on Islamic law in the 2000s, I wanted to write a small book on justice that would incorporate some of that research, as well as some of the work Yale philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff completed in the same period (see my blog Jesus and Justice for a taste of Justice: Rights and Wrongs). Knowing I needed some input from legal theory, I turned to Raymond Wacks’ Philosophy of Law: A Very Short Introduction. I was not disappointed.

In 128 pages Wacks offers an intellectual history of “justice.” At the risk of oversimplifying, let me say that there are three basic ways to look at law and justice:

1. Law and morality are intertwined. In fact, human laws in their general principles flow out of natural law. This is the heritage handed down by the Greeks, and especially the Stoics, for whom “natural” was derived from human reason. This is the current too that impacted the Muslim rationalists, the Mu’tazilites, and also Muslim philosophers such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes). This current was in turn passed on, at least partially, by Muslim Spain to European theologians like Thomas Aquinas. Humans know good and evil, because through creation God imparted this knowledge of objective moral truth to humankind. Any law enacted by humans that goes against natural law (and divine law as revealed in the Scriptures) is not law. The good precedes the right, and this is the current that fed into the Vattel, Hugo Grotius and human rights tradition.

2. Law is man-made and morality is not relevant. This is legal positivism. There are no legal norms outside of humanity and, what it more, law and morality are two different things. For “exclusive” legal positivists like Joseph Raz (b. 1939), law is a social fact and hence, autonomous. It is also the only source of authority in a society, outside of any moral considerations. Other positivists, so-called “soft” positivists, like H. L. A. Hart (d. 1992), see law with a minimum content of natural law; and yes, this content does have moral implications. That said, the law is a system of rules people make to ensure that a human society can function and not be destroyed by people’s selfishness and inclination to violence.

3. The field of “critical legal studies” questions the validity of all formal schemes of human progress, and even the notion of utopia, noting that, above all, law is about power. The history of the Western world is replete with Western states conquering and subjugating other parts of the world, and forcing them to submit to their laws. Globalization for them is mostly a form of neo-colonialism, by which Western economic power – through its multinational corporations and a neoliberal form of capitalism – subverts and drains developing countries from their economic and therefore political potential. Extreme partisans of postmodernism even doubt that there are any possible basis for moral agreement among humans. So much for human rights . . .

Mbaye Lo’s conclusion

Lo has given us a useful snapshot of the jihadis’ mindset about military jihad, but nowhere does he offer a critique of their tactics or theology. I’m sure he has done so elsewhere, or he wouldn’t be teaching where he is. Further, his pedestrian tone seems to dismiss the jihadi threat by saying it’s simply part of a general breakdown of the international order (civilians are killing civilians everywhere) and that, according to his Niamey imam, these are the signs of the end times.

What is more, though he admits that the roots of jihadism are complex, he basically concludes it’s America’s fault:

“I agree with the imam: this is the end of time, scary times, and troubling times. Many factors have contributed in its making. But I still blame the U.S. for abandoning the moral high ground when confronted by militant Islam. It has failed to lead by example, by its moral ideals. A Wolof proverb states, “if the father is a drummer, then no child should be scorned for dancing.” In this instance, the U.S. has led by policy and actions, and the rest of the world has followed its example.”

I am definitely recommending the first position above: law and morality must go hand in hand, and justice is about treating all human beings with respect and dignity. The partisans of critical legal studies certainly have a point about law and power. The United States has reacted to militant Islam in ways that have clearly skirted international law and violated human rights, including a clampdown on the press at home (see Dowd’s column). It all started on Sept. 14, 2001, with the AUMF, which gave the executive branch carte blanche in pursuing the "war on terror." But I would say that if you want to be called “leader of the free world,” then you should lead by example. True, there are many reasons why jihadis do what they do, but foremost among them is their theological orientation.

Plainly, the jihadi movement is now on steroids with the dramatic expansion of the “Islamic State”in Syria and Iraq, with dire consequences for the whole region. I applaud the coalition of British imams (“Imams Online”), representing Shias and Sunnis, who issued a 4-minute video strongly condemning the Islamic State and its tactics of terror. In fact, it seems that this crisis sparked the formation of the coalition in the first place. According to their website, “Senior British imams have come together to emphasize the importance of unity in the UK and to decree ISIS as an illegitimate, vicious group who do not represent Islam in any way.”

Make sure too to read this gut-wrenching piece of soul-searching by an American imam, "Lunacy in the Levant: Deconstructing the ISIS Crisis."

To sum up -- Justice demands the rule of law and the opportunity for all nations to continue the process of hammering out “international law” based on the respect for the “natural” (and I add, “God-given”) rights of all human beings. Yes, the United Nations organization does need reform so that all nations can feed into this process in a just manner. But one way or another we will have to work together to make sure that no group can drive people out of their cities and exterminate others, all in the name of religion. It’s our moral duty to struggle for justice, even until the end of time!

If you’re like me and plan to enjoy a cup of coffee tomorrow morning, we will be in the company of 1.6 billion others across the globe. Coffee is one of the most traded commodities on the planet – at more than $100 billion a year! Still, 70 percent of that coffee was hand picked and processed by small farmers who remain dirt poor. Thankfully, that is changing, thanks to the Fair Trade movement.

I have to add, though, that my cup of coffee tomorrow morning will remind me of the poor farmers I just watched on the screen. They were picking those red beans on the stem, dropping them in a basket tied to their waist, probably doing this all day, and then brought home several large burlap sacs for the next stage of a long, work-intensive process before the coffee beans are ready to be exported.

Just for the record, that cup of coffee is made from 70 of those red berries picked in the forest of Central America’s highlands (or in Africa, or Indonesia, or elsewhere).

That both moving and delightful documentary film I just watched was called, “Connected by Coffee.” Two American coffee roasters take us along on a 1,000-mile trek from southern Mexico to Guatemala, and from El Salvador to Nicaragua, visiting the small farmers – mostly indigenous peoples – who have supplied them with coffee for over a decade. These coffee growers are all organized into cooperatives (the one in Nicaragua was all women) and our two hosts are truly their friends, through thick and thin, dancing with them and, in one instance, crying with them. For the sad fact is that, largely due to global warming, a deadly fungus (“coffee rust”) has destroyed virtually 70 percent of their crops in the last two years. Yet they carry on with their friendship, because “it’s about a lot more than coffee.”

“Connected by Coffee” introduces us to the Fair Trade idea – an amalgamation of the environmental movement, the human rights movement, the feminist and peace movements, and more. Here it’s defined it as “an approach to business that strives to replace exploitation with direct, long term relationships based on dignity, respect and equality.” On a subcontinent where coffee powered most of the economic growth for over two centuries, it has mostly been the symbol of shameless abuse – large plantations run by the rich who treat their workers hardly better than they would treat slaves.

Fair Trade, then, is an encouragement to small farmers to pool their resources and leverage their selling power, to invest in the machinery that enables them to bypass all the middle men, fetch a higher price for their product and export directly.

Revolutions and social justice

I had written about “the fourth world” in my book, Earth, Empire and Sacred Text, and showed how the indigenous peoples of the earth are so often forgotten and shoved aside as the poorest of the poor. I also gushed about how the indigenous uprising in the southern tip of Mexico was launched on the very date the North American Free Trade Agreement was to come into effect, January 1, 1994. The Zapatista movement and especially the nonviolent branch Los Abejas (The Bees), which included 48 different indigenous groups, fought against unfair government policies, violence on all sides of the current conflicts, and the predatory practices of the multinational corporations that effectively crippled their already weak economic potential. Yet their weapons of choice were fasting and prayer, and peaceful marches, including one that ended up in Mexico City.

The Zapatista revolutionary movement caught the imagination of the world as the Internet was just getting underway. Thousands of websites were launched to support their agenda and they became a cause célèbre for the anti-globalization movement, which spread dramatically after the 1999 Seattle WTO protests.

The very first stop in “Connected by Coffee” is to the small village of Acteal, in the southern most Mexican province of Chiapas. That’s where in 1997 a band of paramilitary fighters aligned with the Mexican government mowed down in cold blood – and most of them while worshiping in church – 45 men, women and children. The film shows you a heart-wrenching clip of the funeral, pictures of some of the victims and then you meet Antonio, one of the survivors, who since then helped to start the Maya Vinic coffee cooperative.

Fair Trade is about justice for all, and as Martin Luther King, Jr. liked to say, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

That idea of social justice runs through the whole documentary, and if you didn’t know this before, these countries are still barely emerging from revolutionary movements that fought for equality under the law for all, women, workers, and indigenous peoples alike. So many innocent people disappeared in this caldron of torture and death, with the USA, sadly, almost always backing the wrong side.

This is only the second blog I’ve written on Fair Trade on this website. The first one dealt at length on the issue of Free Trade versus Fair Trade, so I won’t go over that here. But notice the connection once again: the Zapatistas launched their revolution on the day NAFTA came into effect . . .

Closer to home

You also know from my first blog that when my family and I moved from Connecticut to Media, PA in 2006, Media had just declared itself North America’s “First Fair Trade Town.” Fair Trade towns was the brainchild of Bruce Crowther in Garstang, Lancashire, UK. It became a reality in a town meeting in April, 2000. Since then, we count more than 1,500 Fair Trade towns and cities around the world, many small like Media, but others like London, Paris, Rome, Madrid, Oslo, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco.

The American story begins with Hal Taussig, the inventor of a new way for Americans (first for teachers like himself) to spend a vacation in Europe. Connect them to local people and immerse them for a short time in their lives and customs, Hal said. That was the birth of Untours. Hal was always much more than a creative vacation planner. A 2011 article in the Huffington Post called him the “UnMillionnaire” – and for good reason. He literally gave away all his income, lived very simply, and invested everything in the Untours Foundation that lends to innovative social projects that have the best potential for solving problems of poverty.

In 2005 Hal told Elizabeth Killough who was now managing the Untours Foundation that he thought Media should become the first Fair Trade Town on the continent. Understandably floored, Elizabeth looked into it, however, and discovered Bruce Crowther’s movement that was starting to pick up momentum. They contacted Bruce and a year later the Media borough voted to implement the requirements for being qualified “a Fair Trade Town.”

Yesterday I went to visit Elizabeth at the Untours Foundation. I know her well, since I have been a member of the Media Fair Trade committee since 2008 and she has been its coordinator from the beginning. But this time I wanted her to tell me how she felt about all her efforts to promote Fair Trade over the last eight years. Here’s my summary of her main points:

“I’m thrilled with how the movement has mushroomed and attracted so much enthusiasm. The Fair Trade Campaigns movement now has over 1,000 towns, but also a growing number of schools, universities and even religious congregations. Here locally we now have a Fair Trade elementary school; the local high school is Fair Trade and so is the local branch of Penn State University. My one disappointment is that Fair Trade sales haven’t followed. It’s like the organic movement: 40% of respondents will tell you in a survey that they support organic foods, but only 10% actually buy them. Our job is to put ourselves out of business. But we have a long way to go before we can reach a critical mass of consumers who will systematically buy Fair Trade products over all other choices.”