-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

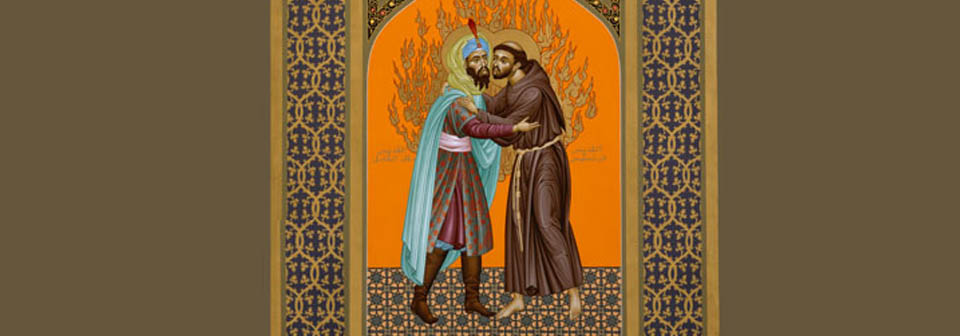

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere rose almost twice as fast in the 2000s than they did in the couple of decades before, says the latest report by the UN-sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Comprised of several hundred experts from all over the world, including scientists and economists, the IPCC regularly distills the latest and most authoritative scientific findings on global warming and its impact on our planet.

In other words, a combination of accelerated use of coal-fired power plants in rapidly emerging economies (especially China) and lots of foot-dragging on the part of rich countries in their commitment to cut greenhouse gas emissions is pushing us dangerously close to the brink of severe disruptions to the life we’ve known so far as humans on this planet.

Yet there is both good news and bad news I want to share in this blog. The good news is that technological advances are quickly bringing down the production of renewable energy like wind and solar. The bad news is that the formidable barons of the fossil fuel industry (coal, gas and oil) are fighting back, desperately trying to resist the inevitable turn to clean energies.

The certainty of human-induced climate change

I’m sure you’ve been reading about the scientific consensus on global warming yourself for several years now. You can also read my own summaries of what’s been published in the “Faith and Ecology” section of my blogs. But in the last nine months the IPCC has produced even more convincing data on global warming and its human footprint.

The IPCC was born as an international body in 1988. Its first milestone was the famous Rio Summit of 1992, which brokered the first environmental global treaty, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This was the result of the IPCC’s First Assessment Report (AR1) in 1990, which pinpointed the rise of greenhouse gases as the cause of the Earth’s accelerated warming.

Three assessment reports followed, the fourth being published in 2007. Three years later, the US National Research Council published a report broadly supportive of the IPCC’s conclusions, saying that “Climate change is occurring, is caused largely by human activities, and poses significant risks for – and in many cases is already affecting – a broad range of human and natural systems.”

2007 was also the year the Noble Peace Prize was awarded jointly to the IPCC and Al Gore for his documentary An Inconvenient Truth.

Many will remember too that there was a backlash, particularly in political circles on the right, alleging on the basis of emails made public that some of the top scientists had exaggerated some of their claims for political purposes. There was much talk of “Climategate.” But that also led to reforms of the IPCC structure and its work has been ongoing.

Finally, the Fifth Assessment (AR5) will be finalized this year in September. As always, there are 3 successive Working Group reports followed by a Synthesis report. The working groups have now issued their reports:

WG1 (Stockholm, September 2013): the probability that climate change is caused by human activity is now rated between 95 to 100 percent.

WG2 (Yokohama, March 2014): “Throughout the 21st century, climate-change impacts are projected to slow down economic growth, make poverty reduction more difficult, further erode food security, and prolong existing and create new poverty traps, the latter particularly in urban areas and emerging hot spots of hunger,” was one of the report’s most striking phrases.

WG3 (Berlin, April 2014): unless the international community can muster the political will to dramatically reduce its current level of emissions in the next decade, the window for achieving a tolerable level of global warming might well be closed.

The Synthesis report is scheduled to come out in September 2014.

Like I said, there is some good new as well. Justin Gillis, reporting for the New York Times, put it this way:

“The good news is that ambitious action is becoming more affordable, the committee found. It is increasingly clear that measures like tougher building codes and efficiency standards for cars and trucks can save energy and reduce emissions without harming people’s quality of life, the panel found. And the costs of renewable energy like wind and solar power are falling so fast that its deployment on a large scale is becoming practical, the report said.

Moreover, since the intergovernmental panel issued its last major report in 2007, far more countries, states and cities have adopted climate plans, a measure of the growing political interest in tackling the problem. They include China and the United States, which are both doing more domestically than they have been willing to commit to in international treaty negotiations.”

That last sentence about China and the US, the two greatest polluters on the planet, is good news indeed! But so is the fact of falling prices of renewable energy – a solar panel costs 75 percent cheaper today than it did in 2008!

Nobel Prize economist Paul Krugman wrote about this in his column last week, stating that sound environmental policy is good for business. Folks on the left and the right – for different reasons – are adamant about green policies shrinking the economy. They’re dead wrong, he asserts. The IPCC panel’s report about “decarbonizing” electricity generation is true, simply because clean energy is booming.

But there are some obstacles. As Krugman wryly concludes his piece,

“So is the climate threat solved? Well, it should be. The science is solid; the technology is there; the economics look far more favorable than anyone expected. All that stands in the way of saving the planet is a combination of ignorance, prejudice and vested interests. What could go wrong? Oh, wait.”

“Ignorance, prejudice and vested interests” are the topic of the next section. Sadly, the battle lines are clearly drawn.

A weakening Goliath fights back

For years now, billionaires Charles and David Koch, owners of the second largest private oil company, have been the target of environmentalist ire. Greenpeace USA published online a large file on Koch Industries – “still fueling climate denial.” I’ll let you peruse the list of think tanks and organizations they have funded in their bid to roll back state and federal incentives for clean energy development. From 1997 to 2011, they spent $67 million, and that pace has accelerated of late.

This past week, the New York Times published an editorial, “The Koch Attack on Solar Energy.” They’ve been funding initiatives, chiefly through the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), to cancel or limit a mandate in twenty-nine states to increase renewable energy production by 10 percent or more by 2015.

In a particularly hard-hitting article, the Los Angeles Times painted the ongoing political storm in these terms:

“The Koch brothers, anti-tax activist Grover Norquist and some of the nation's largest power companies have backed efforts in recent months to roll back state policies that favor green energy. The conservative luminaries have pushed campaigns in Kansas, North Carolina and Arizona, with the battle rapidly spreading to other states.

Alarmed environmentalists and their allies in the solar industry have fought back, battling the other side to a draw so far. Both sides say the fight is growing more intense as new states, including Ohio, South Carolina and Washington, enter the fray.”

That the Big Carbon advocates worry about the renewable revolution is obvious. It’s really a battle of two paradigms. For over a century the US government has supported large power plants owned by capital-intensive corporations. In turn the utilities sell the power to their customers. But what if individual households that collect solar energy could sell their surplus to the wider grid? The new paradigm, one would think, should be a conservative favorite. Yet the Tea Party and the Koch brothers are its main opponents, and, of all things, want to add a tax for people using solar power!

That procedure is called “net metering,” which is practiced in 43 states and the District of Columbia. Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Edward Humes explains it this way in an investigative article in Sierra magazine:

“. . . a policy that requires utilities to purchase energy from homeowners at retail prices. Investor-owned companies hate that; they want to pay the wholesale rate, or less.”

What’s been happening in Hawaii, for instance, is disheartening. Electricity there costs about five times what it costs in many other states, and as a result many have installed solar panels in their homes. In fact, it has a higher proportion of solar users than any other state (1 in 10 on the largest island, Oahu). The largest utility, Hawaiian Electric, resenting the loss of so many customers, has fought back. It simply stopped connecting new solar installations to the grid, under the pretext that these could wreak havoc with the whole system. They would first have to conduct a study, customers were told.

But six months later the study hasn’t been completed and people who’ve invested so much in their solar systems continue to pay exorbitant electric bills while in limbo. Meanwhile, the grid hasn’t shown any wear or tear . . .

You can find summaries for how this battle is shaping up in twenty other states in the Sierra Club article.

But there is one model that threatens utility companies even more than net metering. It’s taking shape in California, as SolarCity partners with electric car company Tesla to build specialized batteries enabling people to bypass the grid altogether. As Humes puts it,

“Even more than net metering, battery storage threatens the utility business model; it could, for instance, allow homeowners to form small, super-efficient neighborhood microgrids that huge, costly utilities could never outcompete . . . More than 300 California households are awaiting the commission’s decision [CA Public Utilities Commission] so they can flip the switch on the solar-battery systems waiting in their garages.”

Meanwhile, solar-generated electricity keeps becoming more reasonable, and citizens groups lobbyng for it are multiplying. One particularly effective one is the Solar Action Alliance.

A short theological postscript

When it comes to the issue of climate change, despite many challenges that vary from place to place, as inhabitants of our one planet we are all equally concerned. But whereas battles rage between Big Carbon, renewable initiatives and many American homeowners, research has shown that it is the poor worldwide who already suffer the most from a warming Earth.

People of faith should see this as a theological – and of course, moral – issue. For western Christians this year, Earth Day and Earth Week followed Holy Week. Jim Wallis of Sojourners wrote on that occasionthat “creation is not just a unique witness to God’s glory — it is, as the apostle Paul wrote, ‘groaning’, waiting also for its redemption.” Resurrection and renewal is not just our hope as people; it is also the hope of a creation marred by human greed and selfishness.

Though Muslims and Jews cannot identify with the “redemption” theme, they certainly buy into the theology of humanity as God’s trustees of creation, called to care for each other and for the beautiful creation we all share. And for this we will each give account on the Last Day.

[The day after I posted this, Justin Gillis was reporting on the National Climate Assessment prepared by a panel of scientists and just released by the US government. That report only brings home with greater urgency the message I was trying to convey above. Also of interest is an article that compares public opinion worldwide on climate change. Just to give you an idea, South Koreans are the most likely to say that climate change is "a major threat to their country" (85%), while Americans are the least likely (40%). In between you find Japan at 72%, Germany at 56%, France at 54%, and Britain at 48%.]

This is a short paper I delivered at the annual meeting of the Society of Vineyard Scholars (part of the Association of Vineyard Churches), held in Columbus, Ohio, in April 2014.

Herein I examine some of theologian Stanley Hauerwas' views in light of a wider discussion about the relationship between the Church and the Kingdom of God. Though I find much to sympathize with his positions, I conclude that, surprisingly perhaps, he ends up with a position similar to Calvin's "Two Kingdoms" theology. The Kingdom of God seems to merge with the Church and the kingdoms of human society seem depraved beyond any possible redemption.

Yale law professor Steven Carter addresses some of my concerns in an article he wrote on Hauerwas. For Carter, who published a book on war the same year as did Hauerwas (2011), Hauerwas' pacifism distorts the reality of violence in the liberal democratic state. Furthermore, his critique undercuts any meaningful role for social justice activism.

As I argued in my blog about Pope Francis, the new pope's discourse about Jesus and the Kingdom of God offers a more biblical view of the work of God's Spirit on the world. The notion of human rights, anathema to Hauerwas, connects organically to both creation and redemption in Christian theology, and it opens the way for Christians and people of all faiths (and no faith) to come together in a brave fight for human dignity wherever people are oppressed and beaten down.

This past week the world remembered with sorrow and a twinge of guilt the tsunami of carnage that descended upon Rwanda twenty years ago. In just 100 days, over 800,000 mostly Tutsi men, women and children had been massacred in cold blood.

A year or so later, Archbishop Desmond Tutu addressed a mass rally brought together by Rwanda’s new leaders, challenging them “that the cycle of reprisal and counterreprisal ... had to be broken and that the only way to do this was to go beyond retributive justice to restorative justice.” Recalling this event in his book No Future Without Forgiveness, he lays out the central theme of his book:

“It is ultimately in our best interest that we become forgiving, repentant, reconciling, and reconciled people because without forgiveness, without reconciliation, we have no future” (p. 165).

I’ll come back to Desmond Tutu, but first, some words of hope about reconciliation and healing where genocide had torn society apart.

Portraits of reconciliation

I was inspired to write this blog upon reading the New York Times Magazine cover article (whence the picture above), “Portraits of Reconciliation.” Here we learn that, twenty years on, photographer Pieter Hugo spent several weeks in Rwanda in March 2014 capturing on film couples made up of perpetrator and survivor of the genocide, who had participated in counseling sessions over several months. Part of a national reconciliation campaign, these people had followed the curriculum offered by one particular NGO called AMI (French for “friend” and an acronym standing for “Association Modeste et Innocent”). They all had arrived at the point where the perpetrator asks the survivor for forgiveness and at least all seven survivors portrayed here (the rest are displayed in a wider exhibit in The Hague, Netherlands) had granted forgiveness in return.

To glimpse at these pairs is to peer into the both dark and luminous souls of fellow human beings, forcing us through their posture and words to confront our own demons of bitterness and resentment, while also catching a glimpse of hope and peace. How can we even imagine going through such a horrific experience ourselves? Yet, the collective portrait is all the more real as it is diverse. Each pair’s body language is different, and though likely a bit befuddled at the cultural cues (Americans would at least force a smile before the camera and they do not), we would notice too the spectrum along which people actually forgive. Some are obviously more at ease than others; some pairs even look like friends.

Considering that over 90 percent of Rwandans attend church regularly, I was surprised that the blurbs given by each person had precious few religious references. One person thanks God for the opportunity to be forgiven. Another, who had knelt down in prayer for her daughters whose bodies she discovered thrown into a latrine, decided to pardon the aggressor for two reasons – she could no longer recover her loved ones and she didn’t want to live a lonely life. Like most of the others, the reasoning was mostly pragmatic:

“I wondered, if I was ill, who was going to stay by my bedside, and if I was in trouble and cried for help, who was going to rescue me? I preferred to grant pardon.”

But mostly, victims found that unforgiveness was an emotional ball and chain they could no longer afford. As this woman put it,

“The next week, Dominique came with some survivors and former prisoners who perpetrated genocide. There were more than 50 of them, and they built my family a house. Ever since then, I have started to feel better. I was like a dry stick; now I feel peaceful in my heart, and I share this peace with my neighbors.”

There is more to this picture. Organizations like AMI have been able to thrive, thanks to a favorable political and social climate. There is no doubt that the ex-rebel Tutsi leader who came in with his troops to stop the bloodletting twenty years ago has done a remarkable job in rebuilding his country, though he’s also a strongman with a spotty human rights record. Alan Cowell writes that “President Paul Kagame … has sought to project his land as a haven of stability and a magnet for investment in a turbulent region. He has taken credit for creating a functioning health care system, raising living standards and improving women’s rights.”

Kagame, to his credit, has facilitated the role of the UN in the work of reconciliation. The New York Times recently editorialized that “Rwanda has done an impressive job of rebuilding its institutions and economy. To bring perpetrators of the genocide to justice, the United Nations has conducted more than 70 tribunal cases, Rwanda’s courts have tried up to 20,000 individuals, and the country’s Gacaca courts have handled some 1.2 million additional cases. Incredibly, Tutsis and Hutus, survivors and former killers, now live side by side.”

But some of the credit for this work of reconciliation must surely go to the architect and engineer of South Africa’s post-Apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) – Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu.

The benevolent shadow of the TRC

Emerging from 27 years of imprisonment, Mandela’s heartfelt pardon for his captors fueled his vision and courage to rebuild a new South Africa. As he put it himself, "If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy. Then he becomes your partner." The hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission began in 1996, as Mandela prevailed upon his friend the Archbishop Desmond Tutu to put off his retirement in order to preside over the proceedings. Tutu wrote about these experiences in his aforementioned book, No Future Without Forgiveness.

As Tutu sees it, the TRC was a deliberate choice in contrast with two other models for dealing with egregious crimes against humanity. The first model, “Victors justice,” as exemplified at the close of World War II at the Nuremberg Trials, was a travesty of justice, mostly because both sides had committed war crimes. On the other hand, the solution chosen by Pinochet, Chile’s dictator, as he handed over the state to civilian authorities in 1990, Tutu dubbed “national amnesia” – a magisterial wave of the magic wand to make past atrocities vanish in thin air. He was granted amnesty and served as Minister of Defense until 1998. Argentina in 1983 had done no better to prosecute anyone responsible for the 3,000 or so people who disappeared under the previous regime.

Instead, the TRC’s third way offered amnesty only to those who would confess their crimes publically. Tell the truth in exchange for freedom, make some reparations and the stage is set (hopefully) for forgiveness and reconciliation. Of course, in practice, it never was that easy. The white community, both Afrikaners and English descendants, consistently ranked it more favorably in the polls than did the indigenous population. In the end, only one out of twelve of those convicted in court was released. Still, South Africa’s TRC, though not the first of its kind, became the model for other such efforts in dozens of other countries since then.

Archbishop Tutu’s 1995 speech in Kigali (Rwanda’s capital) anticipated the actual setting up of the TRC. Retributive justice (victors punishing the loosers à la Nuremberg), as opposed to restorative justice, offers little hope for justice, and hence, for crimes to be exposed, solemnly processed in justice and in people’s minds, and potentially forgiven, one person at a time. After all, states can only do so much to create a climate conducive to reconciliation. There must be a personal dimension, in which individuals buy into the difficult yet highly rewarding task of forgiveness and healing.

I want to end with another important ingredient in the task of forgiveness. We saw that, at least in the limited testimonies provided in “Portraits of Reconciliation,” the faith element in leading to forgiveness was underrepresented. Most of the decisions in evidence was based on practical reasoning. Forgiveness and reconciliation bring both inner peace and foster greater harmony in society. But don’t be too quick to rule out faith!

From Rwanda to Israel-Palestine

Contrary to what is often portrayed in the media, Palestinian civil society (and among Israelis too) is brimming with NGOs dedicated to the practice of nonviolence. I’ve mentioned Sami Awad before, founder of the Holy Land Trust in Bethlehem where I used to teach. Sami’s organizational values are rooted in the belief that peace between Israelis and Palestinians is possible. More than that, HLT members “believe that the Holy Land will one day become a global model for peace, justice, equality and reconciliation between peoples.” Sami, a Palestinian Christian, wanted to understand what Jesus meant by “love your enemy.” He felt God told him that if he was serious about this, he would have to understand from within the suffering of the Jewish people.

So he bought an airline ticket to Germany and spent twelve days visiting several Nazi concentration camps. He even spent one night in a gas chamber. It was life-changing, to say the least! One should not throw around the words “forgiveness” and “reconciliation” lightly, he cautions.

Another Palestinian you should meet is the young Muslim man, Ali Abu Awwad, whom the New York-based Synergos Institute classifies among the most influential “Arab world social innovators”. Since 2005 this young man has spoken to countless groups around the world with a 65-year-old Israeli woman, originally from South Africa, Robi Damelin.

This pairing up, unlike the Rwanda portraits, was not about perpetrator/survivor reconciliation. Rather, it was about a Palestinian and an Israeli who had both lost immediate family members in the conflict. Ali’s brother was shot and killed by an Israeli soldier and he was himself badly wounded by a settler’s bullets. Robi’s 28-year-old son David was killed by a Palestinian sniper. That’s how they met. They had joined several hundred others like themselves in the Parents Circle Families Forum. Understandably, they don’t agree much about the politics of the conflict, but they all believe that there will be no peace without reconciliation between the two peoples.

I urge you to watch their 5-minute presentation at the Summerset House in London, then to read this 2009 article based on an interview of them at the same time. During that interview in a London coffee shop, they told the journalist that the first step toward reconciliation was “to recognize the suffering of the other side.” When you do that, then you are ready to compromise and allow some dreams to die for the sake of peace. Then Robi, as someone who personally struggled against the Apartheid regime in her native South Africa, offered the hope “that the Bereaved Families Forum could inspire a future Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Israel and Palestine.”

Yet more than just fellow campaigners for peace, Robi and Ali had truly adopted each other as mother and son. I tear up (and I smile!) every time I see that clip. In Ali’s words,

“I have found in Robi what I didn't get from my own mother," said Awwad. "She knows what kind of clothes I like, the people I like, and she advises me on all these things. She even knows what food I like.”

‘Shrimps,’ said Damelin, laughing. ‘He is addicted to shrimps.’”

I promised a religious dimension to reconciliation in this section. It was evident in Sami’s case, but not in Robi and Ali’s. Yet they spoke in many mosques together, including the London Central Mosque. As I’m trying to show on this website, a peace discourse rooted in faith is more likely to touch and impel a larger audience to action. As the Qur’an puts it,

“The repayment of a bad action is one equivalent to it. But if someone pardons and puts things right, his reward is with Allah. Certainly He does not love wrongdoers” (Q. 42:40).

I write this during the Christian Holy Week. This Friday we meditate on Jesus’ willing sacrifice on the cross. He who told his followers to love their enemies and forgive those who persecute them prayed these words during his own torture, “Father forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.” (Luke 23:34)

Peace in Syria, the Central African Republic, Israel-Palestine and elsewhere will always be possible where people on both sides are willing to embrace each other’s suffering, to speak the truth about past crimes, to forgive and make reparations. Then reconciliation and peace will have a chance to flourish. Let’s commit to this ourselves and pray for God’s power to lead us in this grueling yet glorious task.

Adis Duderija, currently a Visiting Senior Lecturer at the University Malaya, Gender Studies, is the author of Constructing a Religiously Ideal “Believer” and “Woman” in Islam: Neo-Traditional Salafi and Progressive Muslims’ Methods of Interpretation (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011 -- see my two-part review of his book on this site).

I highly recommend his blog on issues of Qur'anic hermeneutics, particularly as it pertains to gender. You will also find other excellent blogs on issues pertinent to contemporary Islam. It is entitled, "Critical-Progressive Muslims: On Islamic hermeneutics, Gender and Interreligious Dialogue."

Mofed, an Iraqi Christian now a refugee in Amman, Jordan, tells of Muslim gunmen barging into his photo shop in Baghdad and giving him an ultimatum: convert to Islam, or pay a $70,000 tax (jizya), or be killed. It was then that he and his wife packed up and fled. More than sixty percent of Iraq’s million plus Christians in 2003 have left their country.

The cover story in a December 2013 issue of the Christian Science Monitor was entitled “What the Middle East would be like without Christians.” A bit sensationalist, no doubt. Yet, as I said in my previous blog, the situation is dire for Christians in the region where the church was born. The piece’s author puts it this way:

“From Iraq, which has lost at least half of its Christians over the past decade, to Egypt, which saw the worst spate of anti-Christian violence in 700 years this summer, to Syria, where jihadists are killing Christians and burying them in mass graves, the followers of Jesus face violence and vitriol as well as declining churches and ecumenical divides. Christians now make up only 5 percent of the population of the Middle East, down from 20 percent a century ago. Many Arab Christians are upset that the West hasn't done more to help.”

In this second part I only want to talk about Syria. Then I’ll come back to issues of Muslim-Christian relations I brought up in the first part.

Syria’s horrendous free fall

Reading about the suffering of Syria for the last three years is like your worst nightmare – you barely can finish the latest article, because it’s so sad and revolting, and you think it can’t possibly get worse. Yet days, weeks and months pass, and it’s an even more depressing, heart-wrenching experience. No wonder many of us have been numbed by it and have stopped reading about Syria altogether.

I admit. I had come to that point. Then I saw it was the fourth “anniversary” of Syria’s civil war. So I read the New York Times article, “Three Years of Strife and Cruelty Have Put Syria in Free Fall.” Anne Barnard begins with these words,

“Day after day, the Syrian civil war has ground down a cultural and political center of the Middle East, turning it into a stage for disaster and cruelty on a nearly incomprehensible scale. Families are brutalized by their government and by jihadists claiming to be their saviors as nearly half of Syrians — many of them children — have been driven from their homes.”

Yet never before has such a human tragedy and its victims’ desperate plea of help been so graphically documented. Syrians “capture appalling suffering on video and beam the images out to the world: skeletal infants, body parts pulled from the rubble of homes, faces stretched by despair, over and over.”

So no, it’s no just about Christians – every sect (Alawites, Druze, Sunnis, Shias and Christians) and ethnic group has shared in the horror and the loss. And so have its neighbors. Take Lebanon, barely the size of the state of Connecticut: the UN says it has close to a million Syrian refugees and the country’s infrastructure is stretched to the limit.

The loss of Syrian Christianity

I just want to touch on three reasons why, for the sake of the entire Middle East, we should pay attention to the suffering of Christians caught in the civil war inferno.

The first is that their decimation by the violence of war and the deliberate targeting of al-Qaeda-related militia jeopardizes the future rebuilding of Syria on a democratic basis. Hussein Ibish, quoted in the last blog, perhaps says it best:

“Pluralism will be unattainable if long-standing and traditionally well-regarded Christian communities cannot be respected. Forget about skeptics, agnostics, or atheists. Never mind smaller religious groups like Yezidis, Alawites, Baha'is, and Druze. If ancient, large Christian communities find the Arab world fundamentally inhospitable, Muslims will turn on each other just as readily.”

Daoud Kuttab, a prominent Arab journalist – who also happens to be a cousin of Bishara Awad, founder of the Bethlehem Bible College where I used to teach – offered in the Jordanian press a tribute to King Abdullah for his convening a conference on Middle East Christians:

“The emphasis and focus by Jordan on Christian Arabs is of extreme importance in confronting worldwide ignorance of the presence and contributions of Christian Arabs, and the unhealthy growth of the forces of religious darkness and intolerance in this region.

To be effective, such focus must continue in an inclusive and comprehensive way that attracts all and benefits from the great wealth of experience that has made this region so important to humanity and civilisations.”

The idea of religious freedom I mentioned earlier in conjunction with Baronness Warsi and President Obama is also picked by Thomas Farr, a Catholic scholar who directs the Religious Freedom Project at Georgetown University. In this interview, Farr says this about Middle East Christians:

“The exodus of Christians is a serious blow to the prospects of religious freedom, not only because their existence ensures religious pluralism, but also because faithful Christians are uniquely ‘hardwired’ to defend religious freedom for all. Their tradition demands it.”

“The contributions of Christian Arabs” is the second reason why their dwindling numbers bode ill for the whole region. Joseph Amar, who directs the program in Syriac and Middle East Studies at the University of Notre Dame, published a wonderful article on Syrian Christianity in the Catholic magazine Commonweal. Dating from October 2012, Amar’s title was “The Loss of Syria: New Violence Threatens Christianity’s Ancient Roots.”

Christians in Syria, as in the rest of the Middle East, are divided in two main families. The Byzantine, or Eastern family includes the Greek Orthodox Church and the Greek Catholics or Melchites, who, like Lebanon’s Maronites, rejoined Rome just a few centuries ago. The Armenian Orthodox and the Syriac churches belong to the Oriental churches. Those two represent the oldest native churches of the region (add to that group the Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox churches). Armenia was the first nation, which, around 300 CE, officially embraced Christianity.

Unlike Armenian, however, Syriac is a Semitic language almost indistinguishable from the Aramaic Jesus spoke. But I will come back to that issue when dealing with the third reason. Here, it’s important to note that Syriac Christians, along with Jewish colleagues, had already been translating manuscripts from the Greeks long before the rise of Islam. After about fifty years after the Abbasid caliphate had made its capital in Baghdad, the skills and ambition of these Christians caught the attention of the 8th-century caliph, Harun al-Rashid, of Thousand and One Nights fame.

That caliph made a decision that was to positively impact Islamic civilization henceforth and beyond that, Western civilization as well, since the Renaissance was sparked from the creativity and knowledge Europeans had been gleaning from Muslim Spain and further east, as a result of the Crusades. Harun al-Rashid founded the House of Wisdom in Baghdad and hired Eastern Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian scholars to multiply the translation work, research and writing that had been pursued in various centers previously located in Byzantine territory, like Alexandria, Egypt, Nisibis and Edessa (both in today’s Turkey) and in Sassanian territory (Persian), like the Academy of Gundishapur.

Harun’s son al-Ma’mun put a Syriac-speaking Christian (also Nestorian) in charge of all the translation work, Hunayn Ibn Ishaq. Hunayn was already considered the “Sheikh of the translators” with over 116 works under his belt! Thousands of works in Greek, Chinese, Sanskrit, Persian and Syriac were translated into Arabic. Note too that Syriac is a language closely related to Arabic – likely one of the reasons for the prominence of Syriac Christians in this massive, unprecedented collaborative project. The other reason was their own longstanding scholarly tradition.

This of course was the beginning of “Islam’s Golden Age”: by the next century the House of Wisdom boasted the largest collection of books in the world and its scholars built astronomical observatories and expanded knowledge in philosophy, medicine, mathematics, alchemy and chemistry, among other disciplines.

Fast forward to the 19th century. It was “Maronite Christians of Lebanon and Syria [who] were the driving force behind what is known as al-Nahda, the modern renaissance of Arabic that brought about the intellectual modernization and reform of the language.”

The third reason why we should mourn the Christian exodus from this region is that these communities carry within their DNA some of the earliest distinctives of the Christian movement. Some of the most prominent Church Fathers came from North Africa, like Cyprian, Tertullian and Augustine. But they were culturally Roman. Others further east were culturally Hellenistic, writing and thinking in Greek. But the Oriental family of churches in and around Syria had its own separate culture and spirituality. Syriac Christians, alternatively called Assyrians or Chaldeans, look to St. Ephrem as their guiding light.

Ephrem (d. 373) decried the rationalism (especially the Greek philosophical tradition) so prevalent in the Western church of his day. Amar explains,

“For Ephrem, abstract philosophical language and cleverly constructed epistemologies had no place in theology. Divine truth, like life itself, required a subtler, more comprehensive language. Only poetry was sufficiently allusive to intimate the truths of God.”

Sadly, in the next century Syriac Christianity became hopelessly divided and demoralized. Amar quotes the Jesuit scholar Robert Murray who in strong language condemns the way the Western church intentionally repressed and beat down this early Christian tradition. These “cruel and destructive wounds” were inflicted upon Syriac Christians in total disregard for the wealth of spirituality these Christians could have passed on to the wider church. Fortunately, St. Ephrem’s works have been widely translated today and the tide may be turning.

What is also unique to these Christians is that they most likely developed out of the Jewish communities of the diaspora (they spoke Aramaic, after all) who, after the Temple’s destruction in 70 CE, gradually came to appreciate the church’s emphasis on prayer and faith. More than other Christian traditions, the Assyrians are deeply rooted in the Hebrew Bible.

I quoted Reza Aslan’s striking article, “The Christian Exodus,” in my first blog. Tellingly, he begins with the Nusra Front’s attack on Maaloula, one of three Syriac Christian villages of Syria. The jihadists, after several days of occupation, left the village decimated. They desecrated churches and statues, killed several villagers and abducted twelve nuns from a Greek Orthodox monastery.

One last thing I should mention about Syrian Christians: they are united in asking the West to reconsider its support of the opposition forces. Part of this comes from the obvious strategy followed by Bashar al-Assad and his father to favor the members of their own Shia-related sect, the Alawites, along with other minorities like the Christians and Druze. As a result, Christians in Syria and Iraq remained mostly loyal to their dictator. Though they’ve now had to distance themselves from the Assad regime, if only to survive, they are plainly caught between a rock and a hard place.

Here you can read about a high-level, representative delegation of Syrian Christians coming to Washington in order to lobby the White House and Congress to seek a diplomatic solution to the war and stop their support to the rebels.

Muslim voices condemning the attacks against Christians

I already have cited many of these, from King Abdullah, to Hussein Ibish, Reza Aslan and others. Now I briefly highlight two American imams who speak out of their religious convictions to denounce any infringement worldwide on religious freedom, and particularly the actions of their coreligionists in the Middle East.

Imam Muhammad Musri, head of the Islamic Society of Central Florida, was the man who tried to broker a deal with Qur’an-burning pastor Terry Jones. He has drawn the ire of right-wing activists and of more conservative fellow Muslims. His January 2014 piece in the Huffington Post no doubt drew more controversy in some Muslims circles: “Muslims Need to Speak Out Against Persecution.”

He starts off by telling how indignant he was in reading about a Buddhist mob in Myanmar that went around “hacking Muslim women and men with knives.” Then he read the article of a Florida rabbi in the SunSentinel who in commenting about the atrocities committed by Buddhists against the Rohingyas in that country concluded that if such “hatred could flourish in a Buddhist country, it could happen anywhere. Human frailty is universal. No religion, no nationality is exempt.” Musri agreed with that “astute and sobering” remark.

Later he had a chance to look at the Open Doors website (I referenced before) and saw a world map showing where the persecution of Christians was most severe. These were overwhelmingly Muslim-majority countries, most of them clustered in the Middle East, "which is where I was born and grew up.” He then adds,

“In fact, Syria, where I studied to be an Imam, is where the greatest number of Christian were killed last year – 1,213 of them, killed just because they were Christians.

When a people I love, from a region of the world I love, wearing the label of the religion I love, are killing Christians – whom I also love – just because they're Christians, we have a huge problem. And it should be of major concern to every Muslim.”

Imam Yahya Hendi made an even more articulate declaration on the subject. Georgetown University’s Muslim chaplain is also President of Clergy Beyond Borders. Noting how central a role Christians have played in this region for two millennia, he calls on his fellow Muslims to not only reject violence against Christians, but also actually "promote civil harmony and religious freedom in their societies."

As for the Christians in the Middle East, he urges them to “hold fast to their ancient homelands, maintain their historic presence, and not flee to the West. They must continue their witness, and permit their difficulties and suffering to be a sign of hope and peace for their fellow citizens.”

I’ll let you read his 13 principles for yourself, but I’ll quote the next paragraph, as it summarizes so well what this website is all about – reminding Muslims and Christians of their God-given mandate to manage the earth’s affairs in His name and according to His values. Indeed, our Creator has empowered us all with the solemn mission of acting as his trustees in our world. Back to Imam Hendi:

“We Muslims cannot stand silent and must present a prophetic voice of justice and unconditional love for religious minorities amongst us Christians being in the forefront. Muslims must treat others, as they like to be treated and must live the values of Islam, which calls on them to live in light of three values: politics of justice, economics of equity and covenant of community.”

Let’s pray many more come to share this sentiment; that peace and stability will come back to the region, and that Christians will keep a strong witness to God’s love for all, even in the face of brutal suffering. This is, after all, the way of the cross.

Addressing a conference on Christian Arabs he had convened in September 2013, King Abdullah of Jordan emphasized how well established Christians were in the area long before the arrival of Islam and that over thirteen centuries had now passed with almost seamless Muslim-Christian relations. Yet now Christian Arabs are in crisis.

On the same occasion, prominent Jordanian columnist, Jawad Anani, wrote that Christians were the “salt of the earth,” contributing widely to Arab society “in the field of development, nationalism, education, business, medicine, media, literature and the arts.” But sadly many were now leaving the Mideast. He lamented, “If they continue to emigrate, our losses in developing ourselves technologically, security and culture will be negatively affected.”

I hereby begin two blogs on the Christian exodus from the Mideast. In this one, I look at some of the causes and examine the issue of religious freedom. The next blog goes into more regional detail and comes back to the theme of Muslim-Christian relations.

Why the exodus?

Colin Chapman, Anglican clergyman and Islamicist who taught for many years at Beirut’s Near Eastern School of Theology gave a lecture on the past, present and future of Middle East Christians (available here). Here are some of the challenges, he said, that all Christians in the region are facing:

1. An identity crisis: “In cultures in which it is assumed that ‘Arab’ means ‘Muslim’, Christians are made to feel that they don’t belong.” Yes, they massively contributed to the 19th-century Arab literary, scholarly and cultural.

2. A ghetto mentality: Because of many legal restrictions against them and an often difficult minority status over the centuries, Christians tend to fear their Muslim neighbors and despise them.

3. A fear of Muslim radicalism: with the rise of international jihadism since the mid-1990s Christians wonder if that might not become the true face of future mideastern Islam.

4. Economic hardship: Arab Christians are generally well educated, but squeezed by a stagnant economy without job prospects for the youth.

5. American foreign policy: even with the US pulling out of Afghanistan and Iraq, Arabs in general (you can add Turks and Iranians), who have suffered from arrogant and aggressive colonialist policies in the last two centuries, still see the founding of the State of Israel, the continued Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands, and current US hegemony in the region as more of the same. Christians as a result have often been seen as secretly allied to the “Christian West” and have paid a heavy price for it. But never before has violence against Mideast Christians flared up as it has in this new century – hence, the last point I add myself, building on Chapman’s third point.

6. The new wave of violence against Middle East Christians: Imam Yahya Hendi, President of Clergy Beyond Borders, quotes Azizah al-Hibri, professor of law at the University of Richmond and founder the influential Islamic feminist website Karamah (“Muslim Women Lawyers for Human Rights”) in an article that calls on Muslim leaders to stem the tide of Christians leaving the region:

“The desecration of cemeteries in Libya, the murder of clergy in Iraq and Syria, the attacks on churches in Egypt are all beyond the imaginations of civilized nations and educated spiritual region. Recently, suicide bombers targeted worshippers leaving their church in Peshawar and killed at least 60, including women and children and two Muslim policemen guarding the church. A gang of armed terrorists attacked a couple of weeks ago, the sleepy village of Ma’loulah in Syria. Several of its inhabitants were killed, its historic monasteries and churches were pillaged, and the crosses were removed.”

Plenty of other Muslim leaders and scholars are speaking out as well. I want to single out two in particular, Hussein Ibish and Reza Aslan. Ibish was born in Beirut, earned a PhD in comparative literature at the University of Massachusetts and taught Islamics at the American University of Beirut. Today he is best known in his country as a prolific writer and journalist, though he is also a Senior Fellow at the American Task Force on Palestine and based in Washington, D.C. Already in April 2013 he published an article entitled, “Fate of Christians will define Arab Future.” The incident which sparked the piece was an islamist attack on a funeral service in the Coptic Cathedral in Cairo which killed two people and injured ninety. This kind of attack, he writes, sends shivers down his spine:

“As Egypt goes, so goes the Middle East. If the Coptic community of Egypt is thus abused, disparaged, and attacked, what kind of societies are emerging in the Arab world? The regional implications are chilling.

Pluralism will be unattainable if long-standing and traditionally well-regarded Christian communities cannot be respected. Forget about skeptics, agnostics, or atheists. Never mind smaller religious groups like Yezidis, Alawites, Baha'is, and Druze. If ancient, large Christian communities find the Arab world fundamentally inhospitable, Muslims will turn on each other just as readily.”

Of course, this was written before August 14th of the same year, when the Egyptian military government forcibly dispersed the two Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Cairo sit-ins and massacred close to a thousand islamists. That very day, as is documented in a Human Rights Watch video, coordinated attacks by armed men burned and looted dozens of churches, schools and monasteries, with no intervention by the police to stop them before or after. This went one for over a week – which sends a chilling signal to Christians that even the state wants them out, or so it seems.

Liam Stack reported for the New York Times that according to the Maspero Youth Union (Coptic Christian) six Christians were killed, at least 38 churches were destroyed and 23 others were attacked. He added, “An activist with the group, Beshoy Tamry, primarily blamed Islamist leaders for ‘charging their followers with hate’ and trying to destabilize the country by attacking its weakest citizens. The government, though, was hardly blameless, he said.”

So if the prime reason for the dramatic uptick in violence since the 2011 uprisings is political instability, increased state repression and the backlash of islamist violence, the consequence of large numbers of Christians leaving cannot bode well for democracy in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. As Ibish concludes,

“The bottom line is this: if the Arab world, and the broader Middle East, cannot accommodate Christians and other minorities, it won't be worth living in for anybody. And if the region emerges from a period of ethnic and sectarian conflict – of mountanish inhumanity when minorities are hounded out of areas in which they have lived for generations and been an integral part of the culture – those societies will one day look back on it as an unprecedented calamity.”

Iranian-American scholar of religion and bestselling author Reza Aslan recently rankled American evangelicals with his book, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth -- mostly because, like many scholars, he doesn’t take the New Testament gospels as historical accounts. That would have been uninteresting hadn’t he been Muslim and the fact that his portrait of Jesus’ God was Jewish (his followers later called him “God”) and, by the same token, Muslim as well. Most of you will remember that his interview on Fox News was deemed by many as “the most embarrassing interview” of the decade.

What is noteworthy too is that Aslan published in Foreign Affairs a piece in September 2013 with the title, "The Christian Exodus: The Disastrous Campaign to Rid the Middle East of Christians."

Here Aslan describes the August attacks in Egypt as “pogroms,” and the Syrian town of Maaloula, where Christians still speak Aramaic, as a “ghost town” after its being ransacked and destroyed by the jihadist group al-Nusra Front. The Arab Spring, he writes, “may have been the proximate cause of some of the worst violence, but its roots run much deeper . . . What we are witnessing is nothing less than a regional religious cleansing that will soon prove to be a historic disaster for Christians and Muslims alike.”

We’ll explore that scenario in the next blog, but let me end here with a reflection on the global rise of religious violence and the importance of religious freedom for all.

Religious persecution with Christianity at the top

The Huffington Post reports on a recent Pew Foundation study that documents a steady rise of religious violence worldwide. That violence is defined both by intra-religious as well as inter-religious violence. For instance, the intensifying sectarian recrimination between Sunnis and Shias in the ME factors into these figures. Hence we read,

“Social hostility such as attacks on minority faiths or pressure to conform to certain norms was strong in one-third of the 198 countries and territories surveyed in 2012, especially in the Middle East and North Africa, it said on Tuesday.”

Within the general rubric of religious violence, however, the percentage of attacks on religious minorities has noticeably increased – from 27% in 2007, to 38% in 2011, to 47% in 2012. This violence increased everywhere except in the Americas. It most strongly grew in the MENA region. And while Hindu, Buddhist and folk religions (among indigenous peoples) had seen no increase, all the following groups saw a rise in number of attacks against them – in order of highest incidence, Christians, Muslims, Jews, and “Other” which includes Sikhs, Bah’ais and atheists. Countries with the highest “social hostility” were, again in order, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Somalia and Israel.

Furthermore, the percentage of countries imposing religious restrictions on their populations had grown from 29% in 2007 to 47% in 2012. The most severely restricting are mostly very populous as well – in order: China, Indonesia, Russia, and Egypt. But that’s not the whole story, as you will see below.

Yet among the varieties of religious violence, many voices are now separating out the ominous phenomenon of Christian persecution. The megachurch pastor from Nashville, Tennessee, Robert J. Morgan, contributed an article to the Huffington Post recently entitled, “The World’s War on Christianity”. In it he quotes senior Vatican correspondent for the National Catholic Report, John L. Allen, Jr., as saying in his new book, The Global War on Christians (read historian Philip Jenkins’ review) that the rising tide of anti-Christian violence world wide is “the most dramatic religion story of the early 21st century.”

Britain’s first Minister of Faith, the Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, who is also a Pakistani immigrant with both Sunnis and Shias in her family, came to Washington in November 2013 to speak about this very thing – the global persecution of Christians. Speaking at Georgetown University, the Baroness declared that the Christian population was "hemorrhaging," and this "in the very lands that birthed this faith."

Prince Charles delivered an impassioned speech at an interfaith event before Christmas in 2013, expressing how “deeply troubled” he was by the persecution of Christians in the Middle East. Prince Ghazi of Jordan, whom I have singled out before as a dedicated dialog partner, was also present.

That said, the MENA region is not the most egregious in this regard. Morgan, again quoting from Allen’s book, gives us two shocking examples:

“North Korea remains the most evil nation on earth due to the oppression of its people, especially Christians. According to accounts, 80 people were machine-gunned the other day in a stadium in front of 10,000 people. The crime for some of the victims was owning a Bible. Reports from North Korea have told of Christians being pulverized by steamrollers. Hundreds of thousands of believers north of the Thirty-Eight Parallel have simply vanished. At this very moment, there are over 50,000 Christians suffering in concentration camps in Korea.

Turning elsewhere, Christians in India are trying to resist discriminatory laws promoted by Hindu extremists. In the Indian state of Orissa, as many as 500 Christians were hacked to death some time ago, with thousands more injured or left homeless. As many as 350 churches were destroyed.”

The most quoted study on the topic is that published yearly by Open Doors, a Christian organization devoted to supporting the persecuted church. Mostly because of 1,213 documented killings of Christians in Syria, the number of Christian martyrs worldwide doubled from 2012 to 2013. A Reuters article had the following comment on the Open Doors report:

“Nine of the 10 countries listed as dangerous for Christians are Muslim-majority states, many of them torn by conflicts with radical Islamists. Saudi Arabia is an exception but ranked sixth because of its total ban on practicing faiths other than Islam.”

In the list of killings, Syria was followed by Nigeria with 612 cases last year after 791 in 2012. Pakistan was third with 88, up from 15 in 2012. Egypt ranked fourth with 83 deaths after 19 the previous year.”

Why Religious Freedom is good for all

In 1948 forty-eight countries signed the landmark Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 18 reads,

“Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

As we’ve seen here, a lot of social turmoil and violence worldwide would be avoided if this document were applied everywhere. Sadly, that is not the case, and in the MENA region in particular.

President Obama at this year’s presidential prayer breakfast, which gathers people from all faiths from all over for a week of discussions, networking and prayers. He opened his remarks with a word on his own personal faith journey going back to his days of community service in Chicago. His following words drew him naturally into the mainstream of American presidents who, since Jimmy Carter, saw themselves as “born again” Christians:

“And I’m grateful not only because I was broke and the church fed me, but because it led to everything else. It led me to embrace Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior. It led me to Michelle -- the love of my life -- and it blessed us with two extraordinary daughters. It led me to public service. And the longer I serve, especially in moments of trial or doubt, the more thankful I am of God’s guiding hand.”

Then he put on his hat as president of perhaps the most multireligious nation on earth, in a way that would have made Thomas Jefferson proud (see my blog on that). Religious freedom strikes at the root of all religious traditions and strengthens the democratic fiber of all nations:

“Our faith teaches us that in the face of suffering, we can’t stand idly by and that we must be that Good Samaritan. In Isaiah, we’re told ‘to do right. Seek justice. Defend the oppressed.’ The Torah commands: ‘Know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt.’ The Koran instructs: ‘Stand out firmly for justice.’ So history shows that nations that uphold the rights of their people – including the freedom of religion – are ultimately more just and more peaceful and more successful. Nations that do not uphold these rights sow the bitter seeds of instability and violence and extremism. So freedom of religion matters to our national security.” (Applause.)

We started with King Abdullah and ended with the American president. They, along with other people of faith mentioned here, give me hope that the exodus of Christians from their place of origin will be stemmed. It’s already been a “hemorrhage,” as Baroness Warsi put it – 850,000 from Iraq alone since 2003, according to the UN High Commission for Refugees. Still, with the situation varying from country to country as I hope to show in the second half, there are encouraging signs that Muslims and Christians are working together on turning the tide.

In the previous blog reviewing Leila Ahmed’s book The Quiet Revolution we covered the role of colonialism in the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and how these islamists succeeded in reversing a two-generations trend of women unveiling. Only this time, the veil (hijab) adopted by university students in the 1970s and 1980s (and then by women generally) was different in appearance and bearer of multiple meanings.

By the way: “islamism” is the term for political Islam, a distinctly modern phenomenon, started by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt (1928), but then merging in time with a general resurgence of religiosity beginning in the 1970s all over the world and within many religious traditions (see my blog on fundamentalism). In my publications I’ve always written it with a lower case “i,” to mark it off as a political ideology much more than a simply religious one.

After a brief examination of the sociological work done on this reveiling phenomenon, I’ll turn to the wider impact of this movement and its particular impact on Muslims in the United States after the attacks of 2001.

“Why did you take up hijab and Islamic dress?”

Egypt was the first Muslim country where this style of female attire appeared in the 1970s on university campuses, where easily half the population was female. More and more men were growing beards and wearing a variety of looser clothes, like long shirts or the tunic-like flowing djellabas. But they weren’t nearly as noticeable as their female counterparts who were donning newly styled head coverings and a variety of looser clothes that only showed a woman’s hands and face. This was the origin of today’s “Islamic dress” (zia islami), a multi-billion dollar industry flaunted in shops from Marrakesh to Kuala Lumpur and eagerly traded on the Internet.

This was also the time when feminist studies were appearing in American universities. It wasn’t long before researchers came to do their fieldwork in Egypt. Among these, Arlene E. Macleod arrived in 1983 and Sherifa Zuhur in 1988, just as Macleod was finishing her project. By then sixty-nine of her interviewees had begun to wear hijab, and all of them as adults. This change was both a recent and “dramatic” one in their lives – a conversion of sorts.

To illustrate how fast the social scene was changing in these years, Ahmed proposes to contrast the two studies focusing both on veiled and unveiled women.

Macleod first asked women why they thought some women were starting to wear hijab. These are some of the representative answers:

- There was a “general sense that people in their culture were turning back to a more authentic and culturally true way of life”

- In the past people were “thoughtless and misled” but now came to see they had been wrong

- “In the past people didn’t understand that these values are so important, but now everyone has come to see that they are good and strong. So we know we have to act like Muslim women, that is important.”

- One woman now covered said, “Before I didn’t know what I was wearing is wrong, but now I realize and know, thanks be to God.”

- Representing many other women, one put it this way, “We Muslim women dress in a modest way, not like Western women, who wear anything . . . Muslim women are careful about their reputation, Egypt is not like America! In America women are far too free in their behavior!” (119-120)

Still, many of the women were puzzled and not a little worried about these new trends. Sixty percent of the women interviewed admitted they didn’t know why things were changing. Fifty-six percent even opined that it was simply a matter of fashion. I love this answer:

“I don’t know why fashions change in this way, no-one knows why, one day everyone wears dresses and even pants. I even wore a bathing suit when I went to the beach . . . then suddenly we are all wearing this on our hair!” (120)

Over her five years of research, Macleod found no correlation between “increased religious observance” and wearing hijab. To begin with, the lower middle class community that she was studying was religiously observant. In fact, “nearly everyone prayed on Fridays” – though the women mostly prayed at home. One reason that women began to adopt the veil at this stage was because it facilitated their moving around unhindered in public.

Though Macleod admits that this reveiling trend was simultaneously occurring with a general resurgence of “fundamentalist Islam,” she insisted there was no simple correlation between the two phenomena. She also found that it was a women’s “voluntary movement,” “initiated and perpetrated by women.”

Still, there’s more to say, she concedes toward the end of her five-year project. She was noticing that with time men were increasingly putting pressure on their women (daughters and wives) to wear hijab and dress “Islamically.” Religious leaders were proclaiming it from the mosque. Women were feeling the pressure from their peers as well, but throughout this period women always believed that in the end it was their individual choice to wear hijab or not.

This is the context with which Sherifa Zuhur’s study begins. Mosques and Islamic schools had been multiplying in the 1980s and the government, not to be outdone by its islamist opposition, hired many of these recent graduates to beef up existing religious programs in its public schools. By the end of that decade as well, all the top leadership of the professional organizations were islamists, notably among the engineering, law and medical associations.

Zuhur interviewed women who were unveiled and compared their attitudes with believers in “the new Islamic woman” on the issue of women’s rights. Surprisingly perhaps, there were no differences on this matter. Even the most conservative of respondents agreed with the others, that “women should be given equal opportunities with men, and equality under the law so long as principles of the sharia were upheld” (127).

The veiled women strongly believed that unveiled women were disobeying God’s revealed will on the matter and “they saw their own adoption of the hijab to be a sign of their social and moral awakening.” Zuhur found that these women were particularly impressed by the islamist emphasis on “cultural authenticity, nationalism, and the pursuit of ‘adala, or social justice” (127).

What is clear is that a shift had taken place since Macleod’s study: now veiled women didn’t mention practical reasons for adopting the veil, but focused entirely on religious requirements and even activism in the islamist cause. While both sets of women seemed just as religiously observant, they practiced their religion in noticeably different ways. The veiled women were more focused on the “outward” and “visible” practices of their tradition, while the unveiled ones prided themselves in living out the essence (jawhar, or inner reality) of their faith. Even those who might not fast during Ramadan would answer that Islam is about good deeds and much more about how you treat other people than anything you wear or following any public ritual.

The new wave of Islamism was the key behind the changes, notes Ahmed. The Muslim Brotherhood had from the very beginning tried to educate the masses to leave aside their traditional practice of Islam and instead adopt “the engaged, activist ways of Islamism along with all its attendant requirements, rituals, and prescriptions, including veiling” (130).

These were some of the salient features of the new ways of “being Muslim” in the Egypt of the late 1980s and early 1990s that Zuhur picked up in her study. I mentioned Carrie Wickham’s research in the last blog and how it narrowed its focus to the islamists who were energetically winning converts here and everywhere. No doubt there were plenty of sociopolitical factors aiding them in this pursuit – Mubarak’s repressive regime being on top of that list.

I turn now to the United States where this movement was actually given a boost by the anti-Muslim backlash after 9/11.

The veil’s resurgence in post-9/11 United States

Right from the start, both the authorities and the American Muslim community were braced for an anti-Muslim backlash. Two men were shot and killed on September 16, 2001, because they “looked” Muslim (one in fact was a Sikh gas station owner in Mesa, Arizona). President Bush visited the mosque at the Islamic Center of Washington, D.C., remarking publicly that the “face of terror is not the true face of Islam” and that “Islam is peace” (200).

Yet in the following months and years hundreds of attacks on Muslims took place and dozens of mosques were vandalized. Several thousand Muslims were arrested under the suspicion of terrorism, with many of them kept for months without charge. A whole cottage industry of hate discourse directed against Muslims developed too – which I described in a blog as “McCarthyism returns in the 2010s.”

At the same time, thousands of Americans bought Qur’ans and poured into mosques to hear imams tell about Islam. Ahmed tells of a secular Jewish woman attending one of these open houses. Totally turned off by the very concept of monotheism, this lady nonetheless wanted to express her solidarity with a group so wrongly targeted for discrimination and hate.

“Such as scene was unimaginable in any Muslim-majority country,” exclaims Ahmed. “Nor could it have unfolded in this particular way in Europe.” Ahmed felt she was living “a new moment in history.” Many Americans and their Muslim counterparts were now entering a privileged window of time when dialogue and mutual understanding might prevail.

Meanwhile, journalists were reporting that some Muslim women had stopped wearing the veil (several Muslim jurists had given them permission to do so – this was a case of “necessity”!) and that others, not particularly observant before, had been jolted into a conversion experience of sorts and were now wearing hijab and/or Islamic dress.

Why? Reasons varied, but perhaps the common link was pride – one way despised groups often fight back. Also, recall that one of the justifications for the invasion of Afghanistan was to save Muslim women from the oppressive practices of the Taliban that were beating them down. First Lady Laura Bush stated that this was a war “for the rights and dignity of women.” Many American Muslims found that reasoning preposterous: as “collateral damage” in Afghanistan and Iraq their country was killing thousands of women and children, all in the name of name of women’s rights!

That sounded a lot like the old colonial mentality we documented in the last blog. No one wants to be told by a dominant culture that your own is inferior and that you need to adopt foreign values. So this kind of reasoning is reflected in the following responses to “why did you adopt hijab?” But it’s not just pride, as you will see. For many the veil takes on unmistakable political meanings as well:

- For one woman, “putting on the scarf coincided with her spiritual awakening as a devout Muslim, but it was also a reaction to what she perceived to be a growing fear among Muslims in this country” (207).

- For another, she “had taken up the hijab after 9/11 precisely as a way of ‘negating’ the widespread stereotypes about the hijab and Muslims.” She now felt ‘liberated,’ adds Ahmed, “presumably by wearing hijab, from having to passively acquiesce in the face of negative stereotyping” (208).

- Another woman comments, “I felt this is my culture and my heritage. This is something I have to represent. I have changed so much after 9/11, and I think a lot of Muslim women who felt we were being called terrorists really found ourselves researching our own religion and wanting to wear hijab” (208).

- One of the most common answers was “to support the Palestinian cause” – something Ahmed herself discovered in her own interviews with young women in 2002-2003.

- One of those Ahmed interviewed answered this way, “I don’t believe the Qur’an requires it. For me, wearing it is a way of affirming my community and identity, a way of saying that even as I enjoy the comforts we take for granted here and that people of Palestine totally lack, I will not forget the struggle for justice” (211).

Then paradoxically – Ahmed admits that growing up in Egypt when she did this kind of answer was extremely puzzling for her at first – many women wore the veil as a sign of protest against gender biases in their society. Hijab, as a call to justice, included not only protesting the discrimination of minorities but also the suffering and injustice they face as women. For many who wear this post-1970s Islamic dress, walking dressed this way in public is saying to those around them, particularly men, “I chose to wear this because I believe it’s right. Respect me if you respect yourself.”

Leila Ahmed’s takeway

You can find several interesting subtexts in Ahmed’s book, but I’ll focus on her central thesis. After the “unveiling” movement in Egypt from the early 1900s to the 1960s, which was strongly influenced by Western colonial powers, the “reveiling” wave starting in the 1970s was both an anti-Western statement and a practice initiated and defined by the Muslim Brotherhood. Islamism’s ascendency at just that time provided a new way of being “Muslim,” particularly as a woman.

Yet the phenomenon of the zia islami, which has now spread to Muslim communities across the globe, is in no way controlled by islamist leaders and their organizations. Even in the US in the 1970s and 1980s it was Muslim Brotherhood members, or at least MB sympathizers, who founded the Muslim Student Association (MSA) on university campuses and eventually the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA). But since then, these and other Muslim American organizations have evolved into much more inclusive and diverse bodies. Women who choose Islamic dress, therefore, do so for a number of reasons.

The same holds true elsewhere – and nowhere more so than Egypt, where an MB president just one year into his tenure found himself barraged by millions of protesters countrywide, with nearly all the women in these protests wearing hijab. Of course, Ahmed could not have known this since her book was published in 2011. But her thesis still applies here: religion and culture, historical events and evolving sociopolitical realities prove often tough to disentangle.

What we can say is that the hijab and the zia islami from the 1970s on were a brand new phenomenon in Egypt. True, the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamic organizations from the 1930s to the 1950s had used the veil as “an emblem of resistance to colonialism and of affirmation of indigenous values.”

But with the Islamic resurgence in the 1970s “the hijab’s meanings began to break loose from their older, historically bound moorings.” In her own words,

“Today all of these meanings, old and new, are simultaneously freely in circulation in our societies, depending on which community the wearer or observer belongs to. Certainly for some it is still a powerful sign of the Otherness of Muslims . . . a sign of the oppression of women. For many of the hijab’s wearers, on the other hand – who do not live in societies where the veil is required by law – the hijab does not, as their statements typically indicate, have this meaning. For its wearers, in societies where women are free to choose whether to wear it, the hijab can have any of the variety of meanings reviewed in these pages – and indeed, many, many more” (212).

If nothing else (and besides the wonderful historical overview Ahmed provides), this book is a timely reminder that “l’habit ne fait pas le moine” – that, according to the French proverb I grew up with, “the robe doesn’t make the monk.” Or, don’t judge another person on the basis of what she’s wearing.

Like other cultural artifacts, the hijab appeared in a specific cultural and historical context and its meaning evolved as those conditions changed. Part of that context was the modern value of individual agency, and particularly for women. So let us not generalize as to why Muslim women choose to cover their bodies they way they do. A bit of humility and respect, after all, will go a long way to create more meaningful dialog between our various communities of faith.

This is the last blog (1 of 2) on one of the books discussed in our public library within the “Muslim Journeys: American Stories” series: Leila Ahmed’s A Quiet Revolution: The Veil’s Resurgence, from the Middle East to America.

First it was the Christian and Jewish women of Egypt and the Levant who cast aside their traditional head coverings in the early 1900s. A decade later, sparked by Qasim Amin’s controversial book, The Liberation of Woman (1899), Muslim women were beginning to unveil, starting with the upper classes. This was a movement that continued to gain strength, so much so that our author, growing up in Egypt in the 1940s and 1950s, rarely saw any women donning the veil in any form.

Ahmed’s “quiet revolution” is about a groundswell of religiosity accompanied by new “Islamic dress” (al-zay al-Islami) for the women, which took over Egypt in the 1980s while spreading throughout the Muslim world, including to post-9/11 America.

A winner of the 2012 Grawmeyer Award in Religion, A Quiet Revolution, is a stimulating read. Ahmed, Harvard Divinity School’s first professor in women’s studies in religion, taps into her own personal memories, into her own knowledge of the religious dynamics of her home country, into her years of diligent study of women and Islam, and finally into the wealth of sociological research about the reappearance of the veil in Muslim societies.

I first dig into the colonial background to this issue, then into Ahmed’s thesis about the connection between the veil and Islamism, then in the next blog into her observations of Muslim American flagship organizations, primarily the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA).

The Colonial Legacy

Ahmed’s point of departure is Oxford historian Albert Hourani’s 1956 article in the UNESCO Courier entitled, “The Vanishing Veil a Challenge to the Old Order.” Besides chronicling the gradual but irrepressible unveiling movement in Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, largely sparked by Qasim Amin’s book, Hourani unwittingly reveals the attitudes of the region’s intellectuals of his time. As education was offered to both men and women, the latter were less and less willing to submit to the traditional norms of veiling and seclusion. He adds, “In all except the most backward regions polygamy has practically disappeared and the veil is rapidly going” (20).

Hourani tips his hands especially in the following statement: it is “only in the Arab world’s ‘most backward regions’ [my emphasis] . . . and especially ‘in the countries of the Arabian peninsula – Saudi Arabia and Yemen,’ that the ‘old order’ – and along with it such practices as veiling and polygamy – still ‘persist unaltered.’”

Egypt and the Levant in the 1950s were a different world. “Today, in our postmodern era,” notes Ahmed, “it would be almost unthinkable that an Oxford academic would casually use such terms as ‘advanced’ or ‘backward’ to describe cultural practices.” Yet in the mid-twentieth century such sentiments were shared and taken for granted by the ruling classes both in the West and in the Middle East. Unsurprisingly, “Hourani’s narrative is grounded in a worldview that assumed that the way forward for Arab societies lay in following the path of progress forged by the West.” The colonial project, though mostly over politically in 1956, was still in full swing culturally as the modern/Western myth of progress had been internalized by the elites and many others as well.