-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

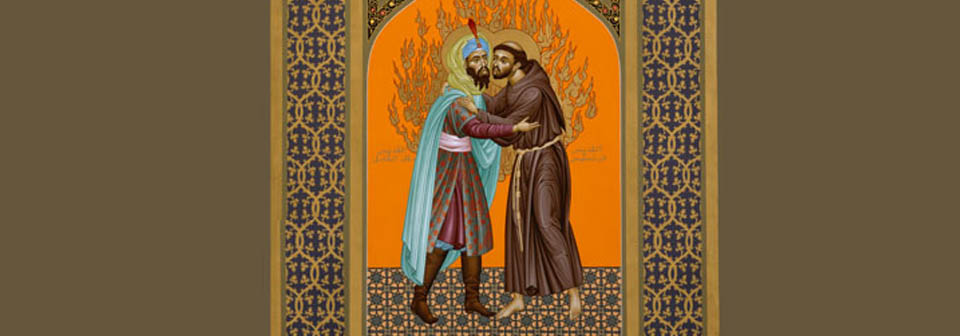

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

A law journal asked me to contribute an article on Muslim and Christian understandings of human rights, so I was thinking about recent sources. Then like most of you, I heard about the Pope’s first “apostolic exhortation” last week – mostly because Francis, as the media portrayed it, was so critical of capitalism.

So, hopeful and curious about the first document authored by the new pope, I decided to read it (about 224 pages in the official pdf version).

I was not disappointed. I found several passages in the Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”) that were helpful for my paper and, more importantly, as a Protestant Christian, I was genuinely inspired by its content and strengthened in my own faith.

But before I get into the document, let me share some of my past to help you make better sense of this blog.

My Catholic experiences in Algeria

Of my sixteen years in the Arab world I spent the first nine years in Algeria (1978-87). I served as assistant pastor for the first four years in the only English-speaking Protestant church, the Anglican Holy Trinity Church, and then five years in the French-speaking Eglise Protestante d’Algérie.

For the first eight years I lived as a single person in community with other internationals related to the church. In fact, my lifestyle was very similar to that of my Catholic friends, priests and consecrated brothers and sisters of various religious orders. We all lived simply, and I would support myself financially through occasional jobs translating or interpreting from French to English or vice versa. In community it was share and share alike and I didn’t need any regular income.

Just a five minutes’ walk from the Anglican church where I first lived was the White Fathers’ Diocesan Center – arguably the best Arabic language school in North Africa at the time. I first went through their 3-year course in the Algerian Arabic dialect and then attended classes with a Lebanese priest who taught modern standard Arabic to Algerian government cadres who had found themselves severely off-balance with the ongoing “Arabization” campaign imposed by the state. Like me (I grew up in France), their education had all been in French. In that setting, Father Mousali was amazingly adept at inculcating Arabic grammar and vocabulary using the newspaper and a love for the language at the same time.

Besides the fact that I made many friends among my Catholic colleagues along the way, two events stand out. The first was my official ordination into the ministry in 1982. I was associated with a small congregational denomination, which, amazingly, approved an ecumenical setting for the ceremony in Algiers. It lasted just under two hours at the Anglican church, with a variety of other clergy participating, including the Catholic archbishop Henri Tessier, who at one point offered a spontaneous prayer of blessing in French, English and Arabic.

Four years later, he attended my wedding, along with Cardinal Duval and a good two hundred other people, Algerian and internationals. Through our common efforts in the Bible Society and in other venues, these exceptional leaders had become true friends.

I have to say, I learned a great deal about spirituality and new depths of the Christian tradition from my Catholic friends in Algeria.

And yes, I’ve been teaching as an adjunct at a Catholic university for the past seven years – another good experience!

Pope Francis and “The Joy of the Gospel”

This document is no official pronouncement on theology or church law, like an encyclical or an apostolic constitution. It’s a pastoral letter by the pope addressed to his worldwide parish, in this case specifically exhorting Catholics to live out their faith so as to draw non-Christians to the love of Jesus that is for everyone. The Church as a whole should be focused primarily on its mission:

“I dream of a ‘missionary option’, that is, a missionary impulse capable of transforming everything, so that the Church’s customs, ways of doing things, times and schedules, language and structures can be suitably channeled for the evangelization of today’s world rather than for her self-preservation . . . As John Paul II once said to the Bishops of Oceania: ‘All renewal in the Church must have mission as its goal if it is not to fall prey to a kind of ecclesial introversion’” (p. 25).

The reformation the Church that he proposes is entirely aligned with this objective – making the Church, from its leaders down to each faithful, truly follow its Master, who lived only for others, and in particular, the poor and disenfranchised. Instead of turning inward, it must turn outward.

Like many previous such papal pronouncements, this one was occasioned by a Synod of Bishops in October 2012 on the theme, “The New Evangelization for the Transmission of the Christian Faith.” So his “exhortation” follows up on the theme of the “new evangelization.” But clearly, Pope Francis feels this theme is providential. You feel it in the passion of his writing:

“The primary reason for evangelizing is the love of Jesus which we have received, the experience of salvation which urges us to ever greater love of him. What kind of love would not feel the need to speak of the beloved, to point him out, to make him known?"

“Sometimes we lose our enthusiasm for mission because we forget that the Gospel responds to our deepest needs, since we were created for what the Gospel offers us: friendship with Jesus and love of our brothers and sisters.”

“A committed missionary knows the joy of being a spring which spills over and refreshes others. Only the person who feels happiness in seeking the good of others, in desiring their happiness, can be a missionary” (pp. 196, 198, 203).

Plainly, Francis believes Jesus is for everybody. But nowhere does he say that embracing Jesus means people become Catholics or Christians. Though of course that remains an option for those who so desire, his concept of evangelism is much broader and more comprehensive. Two concepts help bring this idea into focus. The first is the framework Jesus used for his own teaching – the Kingdom of God:

“The Gospel is about the kingdom of God (cf. Lk 4:43); it is about loving God who reigns in our world. To the extent that he reigns within us, the life of society will be a setting for universal fraternity, justice, peace and dignity. Both Christian preaching and life, then, are meant to have an impact on society” (p. 142).

In a way reminiscent of much Islamic discourse today, Pope Francis contends that religion cannot be restricted to the private sphere or be exclusively about people’s welfare in the hereafter. Rather, “the task of evangelization implies and demands the integral promotion of each human being” (p. 144). He explains:

“Consequently, no one can demand that religion should be relegated to the inner sanctum of personal life, without influence on societal and national life, without concern for the soundness of civil institutions, without a right to offer an opinion on events affecting society … And authentic faith – which is never comfortable or completely personal – always involves a deep desire to change the world, to transmit values, to leave this earth somehow better that [sic] we found it. We love this magnificent planet on which God has put us, and we love the human family which dwells here, with all its tragedies and struggles, its hopes and aspirations, its strengths and weaknesses. The earth is our common home and all of us are brothers and sisters. If indeed ‘the just ordering of society and of the state is a central responsibility of politics’, the Church ‘cannot and must not remain on the sidelines in the fight for justice’” (Benedict XVI, p. 145).

The second concept that informs his view of evangelization is that of Christ’s incarnation. God who sent his Son as a human being in order to redeem the human race continues through his Holy Spirit this work of redemption both in the lives of individuals and in societies writ large. Each human being was created in God’s own image and “is the object of God’s infinite tenderness, and he himself is present in their lives” (p. 204). For this reason God cares too about the social, economic and political structures that bind people together. But it starts with treating our neighbor as if she were Christ himself:

“God’s word teaches us that our brothers and sisters are the prolongation of the incarnation for each of us: ‘As you did it to one of these, the least of my brethren, you did it to me’ (Mt. 25:40). The way we treat others has a transcendent dimension: ‘The measure you give will be the measure you get’” (Mat. 7:2).

God’s infinite care for every human being is what also animates his desire to see justice implemented on all levels of human society. Perhaps the word “solidarity” best captures this aspect of Catholic social teaching, and in particular the message that Pope Francis aims to communicate here.

Pope Francis and human solidarity

We already read this phrase above, “The earth is our common home and all of us are brothers and sisters. If indeed ‘the just ordering of society and of the state is a central responsibility of politics’, the Church ‘cannot and must not remain on the sidelines in the fight for justice.’” This theme must also be placed alongside another Catholic doctrine, the preferential option for the poor. Here is one helpful explanation of it:

“God’s heart has a special place for the poor, so much so that he himself “became poor” (2 Cor 8:9). The entire history of our redemption is marked by the presence of the poor. Salvation came to us from the ‘yes’ uttered by a lowly maiden from a small town on the fringes of a great empire. The Saviour was born in a manger, in the midst of animals, like children of poor families; he was presented at the Temple along with two turtledoves, the offering made by those who could not afford a lamb (cf. Lk 2:24; Lev 5:7); he was raised in a home of ordinary workers and worked with his own hands to earn his bread. When he began to preach the Kingdom, crowds of the dispossessed followed him, illustrating his words: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor” (Lk 4:18).

It is precisely at this juncture that you can begin to situate the pope’s thoughts on economic issues. This is where human solidarity comes into play:

“Solidarity is a spontaneous reaction by those who recognize that the social function of property and the universal destination of goods are realities which come before private property. The private ownership of goods is justified by the need to protect and increase them, so that they can better serve the common good; for this reason, solidarity must be lived as the decision to restore to the poor what belongs to them. These convictions and habits of solidarity, when they are put into practice, open the way to other structural transformations and make them possible. Changing structures without generating new convictions and attitudes will only ensure that those same structures will become, sooner or later, corrupt, oppressive and ineffectual” (pp. 149-50).

It is this divine call to solidarity that sparked this oft-quoted passage of the document:

“Just as the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ sets a clear limit in order to safeguard the value of human life, today we also have to say ‘thou shalt not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills. How can it be that it is not a news item when an elderly homeless person dies of exposure, but it is news when the stock market loses two points? This is a case of exclusion. Can we continue to stand by when food is thrown away while people are starving? This is a case of inequality” (p. 45).

This passage too was often cited in the news – loving one’s neighbor means looking at changing unjust economic structures:

“In this context, some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting” (p. 46).

Francis is clear that he’s not interested in this or that political ideology. Unsurprisingly, an article in the Economist commented on this document under this title, "Left, Right, Left, Left." The truth is, he’s a lot harder to categorize than that.

My only concern in this blog is to point out his robust message of social justice based on the inalienable human dignity of each person by virtue of creation. At the very least, you can sense this kind of compassion fueling Nicholas Kristof’s recent column. What is more, following the example of Jesus will lead us to boldly stake our solidarity with the poorest of the poor:

“It is essential to draw near to new forms of poverty and vulnerability, in which we are called to recognize the suffering Christ, even if this appears to bring us no tangible and immediate benefits. I think of the homeless, the addicted, refugees, indigenous peoples, the elderly who are increasingly isolated and abandoned, and many others” (p. 164).

Reminiscing about my Catholic friends who truly lived in solidarity with the poor in Algeria only reinforces the challenge I feel from Pope Francis’ exhortation. How can I – how can we, no matter what our religious affiliation might be – do more “to leave this world somehow better than we found it”?

I understand your puzzlement in reading my title. Why would I link the illustrious (principal) author of the US Declaration of Independence and its third president with 38-year-old Indian Muslim immigrant Eboo Patel, founder of the Interfaith Youth Core?

The answer is that Jefferson consciously paved the way for Muslims to be citizens of the country he helped to found, just as much as Catholics and Jews – a very controversial idea at the time. And Eboo Patel, hand picked by President Barack Obama to join his inaugural Advisory Council on Faith-Based Neighborhood Partnerships, is a highly effective mobilizer of young people of all faiths for community service across the US. He may also be the most eloquent advocate for religious pluralism as a fundamental American value.

Before I turn to Jefferson, let me say that this blog grew out of the third public library discussion in the series “Muslim Journeys: American Stories” sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the American Library Association. I had posted a blog on the first book we discussed, explaining more about this series in September (“The First American Muslim Celebrity” ). This time it was Eboo Patel’s book, an autobiography and the story of the Interfaith Youth Core, Acts of Faith: The Struggle for the Soul of a Generation (Beacon Press, 2007).

About “Jefferson’s Qur’an”

It so happened that one of the books our library chose to display for this series of discussions was just published, Denise A. Spellberg’s Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders. Spellberg, who teaches history and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, tells in an interview (in one of the largest pan-Arab newspapers, Al-Sharq al-Awsat, published in London) how she accidently ran into an advertisement for a play in Baltimore, Mohamet the Impostor in 1782. Intrigued by the fact that Islam seemed to be much more known and discussed in early America than she had previously thought, she also wondered whether there might not be other more favorable views about Muslims and Islam.

Two years later, she found evidence of that view, which, though limited, was being presented forcefully by some rather articulate and powerful people, including some politicians and lawyers in North Carolina. There were also founding fathers like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

A good eleven years before he wrote the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson, still in law school, purchased a 2-volume copy of the Qur’an – which resurfaced in public view, by the way, when Representative Keith Ellison swore allegiance in 2007 with his hand on this Qur’an. We know from future events that Jefferson most likely consulted this Qur’an several times in his life.

But the most likely reason for his purchase was his keen interest in the works of English philosopher of the previous century, John Locke, and a few other intellectuals of the time who believed that Muslims should, along with people of other faiths, enjoy civil rights in the Commonwealth. Here’s how Spellberg puts it in her Introduction (see this long excerpt):

“Because of these European precedents, Muslims also became a part of American debates about religion and the limits of citizenship. As they set about creating a new government in the United States, the American Founders, Protestants all, frequently referred to the adherents of Islam as they contemplated the proper scope of religious freedom and individual rights among the nation’s present and potential inhabitants. The founding generation debated whether the United States should be exclusively Protestant or a religiously plural polity. And if the latter, whether political equality—the full rights of citizenship, including access to the highest office—should extend to non-Protestants. The mention, then, of Muslims as potential citizens of the United States forced the Protestant majority to imagine the parameters of their new society beyond toleration. It obliged them to interrogate the nature of religious freedom.”

Years after he drafted the Virginia Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786) and later as president, after he had fought a war against the Muslim ruler of Tripoli, he stated that the bill intended to include Muslims. As ambassador in London (1786) and later as president, Jefferson negotiated with two Muslim ambassadors. On the second occasion, in Washington, DC, Jefferson delayed the state dinner from the afternoon to after sunset because of the Ramadan fast.

We know too that Jefferson made use of his knowledge of Islam in a letter he wrote to the two leaders of Tunis and Tripoli with whom he was at war at the time (for more on this, see my blog, "Barbary Pirates and a US Treaty"). In one of them he chose to close with a benediction, asking God to “preserve your life, and have you under the safeguard of his holy keeping.” This obvious reference to the God of monotheism, likely meant to tone down hostilities, is all the more interesting, given that Jefferson himself was more of a Unitarian and deist than a Christian.

The data Spellberg uncovers about Jefferson and his attitude to religious freedom and Muslims in particular – all of this sounds very familiar today. Jefferson was the first American president “to suffer the false charge of being a Muslim, an accusation considered the ultimate Protestant slur in the eighteenth century.” Barack Obama was the second.

It’s true that Muslims were brought into the debate about religious freedom almost as a theoretical foil, since Jefferson did not seem to know that thousands of American slaves were actually Muslims. It was more of a trope to offer full citizenship to Catholics and Jews. Still, unlike President John Adams, Jefferson did not see the checkered US relationship with the Barbary Muslim states as anything to do with religion. If anything, religion for him might be a tool for improving those relations.

My last point has to do with today’s conservative discourse making much about Islam being foreign to American history and values. Islam was vigorously debated during the founders’ generation. I quote again from Spellberg’s Introduction:

“The cast of those who took part in the contest concerning the rights of Muslims, imagined and real, is not confined to famous political elites but includes Presbyterian and Baptist protestors against Virginia’s religious establishment; the Anglican lawyers James Iredell and Samuel Johnston in North Carolina, who argued for the rights of Muslims in their state’s constitutional ratifying convention; and John Leland, an evangelical Baptist preacher and ally of Jefferson and Madison in Virginia, who agitated in Connecticut and Massachusetts in support of Muslim equality, the Constitution, the First Amendment, and the end of established religion at the state level.”

Eboo Patel and American religious pluralism

Recall Spellberg’s quip: “The founding generation debated whether the United States should be exclusively Protestant or a religiously plural polity.” Eboo Patel exemplifies – admirably, and with great energy and charisma – this ideal of the United States as “a religiously plural society.”

His book, Acts of Faith, tells a compelling story of a young immigrant born in Mumbai, India, who grew up in the suburbs of Chicago trying hard, like every other teenager around him, to fit in. Drifting at first – he and his brother were “more focused on being goofballs than getting good grades” – his life changed when a middle school science teacher challenged him to earn his way into the Challenge science class. And he did! From then on Patel embarked on an academic path that eventually sent him to Oxford University on a Rhodes scholarship.

I’ll highlight only a few details of his life – I really do want you to read this book! – touching on two themes that impacted his life mission of stirring up interfaith youth activism.

The first is about how his successive girl friends mirrored and shaped his own religious journey. In high school it was Lisa, the bright Mormon girl with whom he would spend hours discussing highbrow literary works. Then they were off to college, Lisa to Brigham Young University and Patel to the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. Lisa, realizing that Eboo was not going to convert to Mormonism, wrote a farewell letter. Eboo, sobbing now, realizes that in fact he too had already moved on. College life was filling his lungs with fresh air, of which he wanted so much more!

That is where he meets the Jewish student Sarah. That relationship lasts much longer and generates many more shared experiences – even doing a summer road trip across the US. Sarah however, increasingly drawn to her Jewish roots, decides to do a year of study in Jerusalem, where Eboo comes for a visit. Perhaps it was inevitable, but in the end Sarah tells Eboo it’s best they part ways. Through many tears once again, Eboo tells her she’s lucky to have found a religious community to which she can wholeheartedly belong.

True, Patel’s family had raised him in the ways of Ismaili Shia Islam. Shia Muslims are only about 15% of all Muslims and maybe 10% of those (about 10 million) call themselves Ismailis, looking to the Harvard-educated and philanthropist extraordinaire Aga Khan as their spiritual leader (“Imam” in the Shia sense). As a boy Eboo’s mother taught him the special prayers that Ismailis recite once in the morning and twice in the evening. But both parents were highly successful professionals whose religion in practice was little more than being good people in society. If anything, it was his Indian grandmother who most influenced his faith, insisting from the start he marry an Ismaili (listen to his TED Talk about the female influences on his life).

Eboo Patel in college was still searching for spiritual meaning anywhere and everywhere. Even at Oxford, he fell in love with a beautiful Hindu woman. Still, he was beginning to yearn for his own path. The turning point happened when he and his Jewish friend Kevin, who until then was trying hard to be a Buddhist, meet the Dalai Lama in India, thanks to the intervention of a Chicago Catholic monk, Brother Wayne. By this time, the idea of an interfaith youth alliance for community service was beginning to take shape and the Dalai Lama embraced it immediately – especially the service aspect. But just as significantly, the Dalai Lama stressed how crucial it was, if such a project was to succeed, for them to be better grounded in their respective Jewish and Muslim identities. He urged them to hold on firmly to their own faith while saluting the best in the faith of others.

The second theme I wanted to highlight about Patel’s journey has to do with the word “service.” Perhaps even more influential than the women he loved along the way, were his own experiences in community service. His parents had involved him early on in the YMCA and Patel had immersed himself in soup kitchens and in tutoring disadvantaged children throughout high school.

Then in college he discovered the Catholic Workers houses, the movement Doris Day had launched. And even later when settling in a poor neighborhood of Chicago to teach in an alternative school for drop outs, he lived for many months at the St. Francis Catholic Worker House. A year later he was basking in the success of a weekly potluck dinner he had started and that was now drawing about a hundred young adults, all engaged in some form of community service. But most of them were very secular, and it dawned on him that the tradition of service to the less fortunate he learned from his parents as part and parcel of their Ismaili Muslim faith really did need a spiritual component.

It was thanks to a convergence of factors involving Brother Wayne and another mentor committed to interreligious dialog that Interfaith Youth Core was born. In a way, it was a happy marriage between the bohemian and generous spirit of the non-religious twenty-somethings who flocked to those potluck dinners and the growing interfaith movement that he and Kevin discovered through Brother Wayne – people sharing their religious faith with one another, but focused on common service.

Speaking of marriage, you’re probably wondering about Eboo Patel's love life. Soon after the launching of the IFYC, he finally listened to his friend Kevin’s advice and looked up this Indian-American civil rights attorney friend of his. And good thing he did. It was love at first sight! She too was from the Gujarat state of India, a Sunni Muslim who nonetheless came to appreciate (but not embrace) Eboo’s Ismaili faith. A few months before the wedding, Eboo had come full circle. His grandmother in Mumbai welcomed her grandson’s fiancée with open arms, greeting her in the Sunni way, “As-Salaamu alaykum!” Even in his own marriage, he would model pluralism.

Theological pluralism and civic religious pluralism

One of the most respected voices in promoting “a religiously plural society” in America today is Prof. Diana Eck who heads the Pluralism Project at Harvard University. Since 1991 Eck and her teams across the country have conducted research on how people of different faiths are coming together in America’s cities to make them better places. Think about it. This kind of advocacy is promoting a level of interfaith understanding of which Jefferson and his ilk could only dream. That is exciting. And many individuals and organizations are creatively and courageously moving the bar of interreligious dialog higher, despite all the hatred and bigotry that still captures much of the discourse in this country.

Eboo Patel’s intuition is unique among these voices. “Reach the youth in their teens and give them positive experiences of serving alongside teens of other faiths,” he urges. As IFYC has shown, these are life-changing experiences for them, which will only multiply as they grow older and train their own children.

There is one more aspect of Patel’s work I want to close with. In the beginning, he found it difficult trying to coax religious leaders to sent their youth to the IFYC. They were all reticent for the same reason: “our youth barely know their own faith tradition – won’t they get confused in sharing with kids of other traditions? Worse yet, won’t they be tempted to convert to other faiths?”

Patel developed the following points to explain the IFYC:

1. Young people are already immersed in their schools and neighborhoods in a religiously plural society. The challenge is: how can they maintain their own religious identity?

2. The IFYC is committed to strengthen those identities (helping them to become better Catholics, Buddhists, Muslims, etc.).

3. “The truth is, our religious traditions have competing theological truth claims, and we simply have to accept those” (p. 166). There is no use arguing, for instance, about what “salvation” is, or who is “saved.” Religions are definitely not the same.

4. The IFYC’s approach is “shared values – service learning.” Starting with the values different communities of faith hold in common, like friendship, loyalty, compassion, mercy, and hospitality, the leaders encourage kids to think about how their tradition teaches those values. And usually a story comes up.

5. To sum up, writes Patel, “the only route to collective survival really, is to identify what is common between religions but to create the space where each can articulate its distinct path to that place. I think of it as affirming particularity and achieving pluralism” (p. 167).

So in effect, there are two kinds of pluralisms. Theological pluralism is a theological view stating that differences between religions are only surface deep, but that in the end they all come out in the same place. Put differently, they are all different paths up to the same mountaintop.

Patel disagrees, as do I (and as does Stephen Prothero in the book I use in my Comparative Religion class, God is not One). Each religion answers different questions relative to the human condition. And when the questions are similar, the answers differ.

By contrast, civic religious pluralism is simply a formula that recognizes that in all the global cities of our day (and especially in the west), people of many faiths live side by side. In order to diffuse tensions and avoid potentially disastrous conflicts, these diverse communities must find ways to interact meaningfully and respectfully. They must be willing to listen and learn from one another, and commit to build on common values so as to work for the common good of all.

John Locke in 17th-century England and many of the 18th-century American founders already realized that civil rights – including freedom of conscience and religion – by definition must apply to all citizens, no matter what their religion. Class and race did not yet figure in their calculus, as their reliance on slavery sadly testified. Yet theirs was a conviction about human dignity that was to grow, widen and mature beyond the stain of colonialism and the barbarity of two World Wars. In fact, are still trying to work out the implications of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

Eboo Patel stands firmly in this legacy, strategically choosing to focus on the younger generation of Americans. Religious pluralism is indeed an “American” value – a profoundly civic virtue. It is also our best hope for a more peaceful and just world for all its peoples. Though we may define “God” in different ways, we are all called to be his trustees on the planet we share. May we all live up to this sacred trust, starting with the most vulnerable in our own neighborhoods.

My first blog dealt with the interpretive assumptions and methods of the Salafis (the “Neo-Traditionalists” in Adis Duderija’s book, Constructing a Religiously Ideal “Believer” and “Woman” in Islam). So who are these “progressive Muslims” who stand in such contrast to the ultraconservative Salafis?

In his Introduction, Duderija announces that for the second half of the book he will be “drawing on the works of leading progressive Muslim thinkers such as Khaled Abou El Fadl, Omid Safi, Farid Esack, Ebrahim Moosa, Kecia Ali, Amina Wadud, and others” (p. 3). All but one (Farid Esack, and maybe Amina Wadud nowadays) are academics teaching in American universities. What they do have in common, at least in terms of this label, is that they and others contributed to a sort of manifesto in 2003 – a book Omid Safi edited, entitled, Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism.

But lest you think it’s all about American Islam, Safi wrote this in an article that same year:

“Progressive Muslims are found everywhere in the global umma. When it comes to actually implementing a progressive understanding of Islam in Muslim countries, particular communities in Iran, Malaysia, and S. Africa are leading, not following the United States” (quoted in Duderija, pp. 121-2).

Duderija explains that progressive Muslims share in the general reforming trend of the “classical modernists” of the 19th century – Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Sayyid Ahmed Khan and Muhammad Abduh. They also represent a clean break from that “modern” movement. That’s why I didn’t hesitate to write that Duderija himself was writing from a “postmodern” perspective (a complex idea that my book Earth, Empire and Sacred Text – now in paperback – seeks to elucidate).

At the risk of oversimplifying, here are three areas progressive Muslims are most concerned about (realize too that this is a very diverse group of people with a whole spectrum of views on many things and who, additionally, pride themselves in that diversity!):

1. Postmodern hermeneutics: they believe language is fluid, evolving and giving rise to multiple meanings. Hence, a text doesn’t speak for itself. What is its literary genre? What are the circumstances of its production? What is known about the author? But equally, what are some of the lenses through which a particular reader or commentator has approached the text? Personality, culture, sociopolitical circumstances, academic discipline, school of thought and more – these are some of the filters that affect how the text is absorbed and understood. But it’s not only true that we have to investigate a sacred text’s historical context if we want to interpret it correctly, but also that no interpretation is final, since readers at different times bring different questions and concerns to the text. In the end, meaning is mostly constructed by the reader – like what I said about theology in the first blog. It too is always worked out in particular contexts and therefore remains a very tentative, ongoing, and hopefully humble enterprise.

2. Ethical values are paramount: without discarding or even disparaging the rich legacy of Islamic law (Shari’a in the sense of fiqh – the accumulated jurisprudence of the four Sunni schools of law and the Shi’i Ja’fari school), progressive Muslims view that body of knowledge as honorable but also time bound. Another way of putting this is to return to my first two of three lenses I offered in the previous blog. They reject ethical voluntarism (something is “good” because God commands it) in favor of ethical objectivism (good and evil are moral absolutes, i.e., they exist independently of God and humans). With regard to their theology of humanity, they believe that humanity’s divine calling as God’s earthly trustees equips and mandates them to rule over creation with justice, compassion and love. Specifically, they are to defend the rights of the poor, the discriminated against and the most vulnerable (especially women) and fight all manifestations of arrogant power (“empire”) so that all human beings are given the chance to live free, with dignity and the basic amenities of life.

This means that any past rules and injunctions of Islamic jurisprudence that do not meet these criteria need to be revised to fit humanity’s new understanding of a good society. After all, these values are clearly taught by the Qur’an and the Sunna. Human rights, therefore, democracy and the rule of law apply to all, Muslims and non-Muslims. International law is a necessary requirement of a world of nation-states and deserves to be continually submitted to debate and refinement by members of the international community.

3. A politics of liberation: Farid Esack is a veteran of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa and Omid Safi is an Iranian-American who is outspoken in his critique of both the authoritarianism of the Mullah-driven Iranian regime and the arrogance of the global American empire. Social justice not only means liberation for those economically oppressed by neoliberal capitalist policies and the selfishness and greed of the rich. It also means gender justice, which they see as a crying need in most Muslim-majority countries. Hence, a vibrant feminist discourse runs through most of their literature and animates their activism in many places.

The progressive Muslims’ “ideal believer”

Only three authors from this perspective have written about this topic, the South African Farid Esack, the Syrian Muhammad Shahrur and the late Nasr Abu Zayd who was condemned as an apostate by a Cairo Shari’a court in 1995 and finished his career in the Netherlands. For my purposes here, I’ll stick with Esack and his book, Qur’an, Liberation and Pluralism: An Islamic Perspective of Interreligious Solidarity against Oppression (Oxford: Oneworld, 1997) and Duderija’s general thread about how progressives see the issue of the religious Other.

Here is a summary of some of the points Duderija makes in this section of his book (pp. 169-77):

1. The Sunna is much more than a collection of hadiths, bearing in mind too that progressive Muslims are much more skeptical about the authenticity of most of these individual reports. So with respect to the “religiously hostile” hadiths quoted especially by the Salafis, “they contradict the concept of Sunna as based on the overall Qur’anic attitude . . . toward the religious Other as well as on the Prophet’s praxis [or “practice,” a term Esack borrowed from Christian liberation theology], which is an embodiment of that attitude” (p. 171, emphasis his).

2. The Qur’an embraces a position of inclusivism, even of pluralism, with regard to other faith traditions. Term like islam (submission to God), iman (faith in God), kufr (unbelief), ahl al-kitab (people of the book), din (debt, obligation, but later used at “religion”) and the like do not point to a particular “reified” religious identity and institutional framework (as “Islam” came to be known subsequently), but rather are dynamic and “multi-dimensional, i.e., having a number of meanings and connotations ranging from an intensely personal/spiritual to doctrinal, ideological, and sociopolitical, but all of which are inextricably intertwined.” Those meanings change over time, he adds, and “they are linked to issues of righteous deeds and conduct, i.e., to orthopraxis [“right action,” as opposed to orthodoxy, or “right doctrine”).

Some Qur’anic verses are often cited in this regard:

“To each of you We have prescribed a Law and an Open Way. If Allah had so willed He would have made you a single people but (His plan is) to test you in what He hath given you: so strive as in a race in all virtues. The goal of you all is to Allah; it is He that will show you the truth of all matters in which ye dispute” (Q. 548).

“If it had been the Lord’s Will they would all have believed all who are on earth! Wilt thou then compel mankind against their will to believe!” (Q. 10:99).

[The immediate context is the permission to fight in self-defense] “Did not Allah check one set of people by means of another there would surely have been pulled down monasteries, churches, synagogues and mosques in which the name of Allah is commemorated in abundant measure?” (Q. 49:13; see also 22:40).

“Those who believe (in the Qur’an) and those who follow the Jewish (Scriptures) and the Christians and the Sabians and who believe in Allah and the last day and work righteousness shall have their reward with their Lord; on them shall be no fear nor shall they grieve” (Q. 2:62; 5:69; 22:17).

3. Faith in God is tied to good works, and especially the mandate to bring about social justice. This is one of the main points of Esack’s book based on his own experience of nonviolent struggle against the evil apartheid regime in the 1980s alongside people of other faiths, and in particular Christians steeped in liberation theology (its origins go back to Marxist-inspired Catholic groups in Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s; it then attracted many Protestant theologians in South Africa and elsewhere).

This connection is clearly drawn in the last verse quoted above, yet it can be seen consistently taught throughout the Qur’an, as in the Bible, of course (consider Jesus’ teaching that a tree is known by its fruits and James’ emphasis on the idea that faith without works is dead). In this respect Duderija quotes from Khaled Abou El Fadl’s hard-hitting book, The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists. Abou El Fadl, who is also the editor for the series of books in which Duderija’s was published, draws a stark contrast between the “Puritans” (or extremists, of Salafis of all types) and the “moderates":

Moderates argue that not only does the Qur’an endorse [the] principle of diversity, but it also presents human beings with a formidable challenge, and that is to know each other [Qur’an 49:13]. In the Qur’anic framework, diversity is not an ailment or evil. Diversity is part of the purpose of creation, and it reaffirms the richness of [the] divine. The stated goal of getting to know one another places an obligation upon Muslims to cooperate and work towards specified goals with Muslims and non-Muslims alike” (quoted in Duderija, p. 177).

The progressive Muslims’ “ideal woman”

On this this topic the literature is vast indeed. Yet apart from some differences in emphasis and methodology, these feminist writings agree on the essentials. As Duderija puts it, the views of the Neo-Traditionalist Salafis (NTS) are “sociologically contingent and tainted.” He continues,

“Thus, they reject the classical view of the inherently active female sexuality and the concept of the female body being innately morally corrupting . . . They also consider the NTS conceptual linking of women to the notion of causing social chaos (fitna) is based on flawed assumptions concerning the nature of female (and by implication male) sexuality.”

The misogynistic hadiths often quoted by NTS writers are “considered essentially as remnants of the patriarchal nature of the interpretive communities in the past.” In the words of Indian scholar Muhamad Ashraf, “Progressive Muslims have long argued that it is not religion but the patriarchal interpretation and implementation of the Quran that have kept women oppressed” (p. 178).

Specifically, these are some of the hermeneutical strategies this school uses to “construct” an egalitarian theology of gender (a very partial list):

1. Keeping the historical context in mind, while separating the contingent from the universal: take this verse that tells the believing women to cover themselves with a jilbab (large, loose cloth like a cloak):

“O Prophet! Tell thy wives and thy daughters and the women of the believers to draw their cloaks close round them (when they go abroad). That will be better, so that they may be recognised and not annoyed. Allah is ever Forgiving, Merciful” (Q. 33:59).

Asma Barlas, in her book, Believing Women in Islam: Unreading Patriarchal Interpretations of the Qur’an, shows that the cultural context in 7th-century Arabia was that of slavery:

“[In] mandating the jilbab, then, the Qur’an explicitly connects it to a slave-owning society in which sexual abuse by non-Muslim men was normative, and its purpose was to distinguish free, believing women from slaves, who were presumed by jahili men to be non-believers and thus fair game. Only in a slave-owning jahili society, then, does the jilbab signify sexual non-availability, and only then if jahili men were willing to invest in such a meaning” (quoted in Duderija, p. 180).

So the command to wear a body-covering veil was not meant for women at all times and places. Khaled Abou El Fadl agrees with the slave woman/free woman distinction but also comments on Q. 24:30 (“let women cover their bosoms with their head cloths”). He argues that that the khimar (like a large scarf) worn around the neck was often thrown back leaving the head and chest exposed. In fact, women in Mecca and Medina at that time, he adds, often had their chest partly or wholly exposed, even if their heads were covered. Also the phrase “and to display of their adornment only that which is apparent” points to the prevailing societal custom, a category in fact within Islamic jurisprudence. In that context, it was often to include current practices as perfectly acceptable, except that with the passage of time these conventions became sacrosanct and unchangeable.

2. Focus on the equality verses: if you decide that verses cannot be taken out of context and that the context includes the whole of the sacred text, then you can take a further step by stating that those verses that exemplify the overarching ethical values of the Qur’an are the only ones meant to be universally applicable. I’ve written elsewhere about the popular movement in Islamic law today that is focused on the “purposes of the Shari’a” (maqasid al-shari’a). Those are first and foremost the wellbeing (maslaha) of humans in this world and the next; but then also all the values of justice, equality (including gender equality and justice), compassion and love (especially in the context of marriage). So the following texts become the standards by which all other verses are classified (given here in M. A. S. Abdel Halim’s Oxford World’s Classics translation):

“Another of His signs is that He created spouses from among yourselves for you to live with in tranquility: He ordained love and kindness between you. There truly are signs in this for those who reflect” (Q. 30:21).

“It is He who created you all from one soul, and from it made its mate so that he might find comfort in her” (Q. 7:189).

“People, We created you all from a single man and a single woman, and made you into races and tribes so that you should get to know one another. In God’s eyes, the most honoured of you are the ones most mindful of Him: God is all-knowing, all aware” (Q. 49:13).

“To whoever, male or female, does good deeds and has faith, We shall give a good life and reward them according to the best of their actions” (Q. 16:97).

Hadiths:

“Women are but sisters (or twin halves) of men.”

“The best of you are those who behave best to their wives.”

“The more civil and kind a Muslim is to his wife, the more perfect in faith he is.”

These and other verses, argue progressive Muslims, repudiate the wrongheaded assumptions of the classical jurists (and many transmitters of hadiths before them), according to which women are “essentially sexual rather than social beings,” and therefore inferior by nature to men. As in other cultures of the ancient near east – all strongly patriarchal – gender inequality was assumed to be part of the natural order of human existence. For all these peoples a “woman’s biology determined her destiny” and marriage contracts included elements common to slave-owner relationships (“in essence, a woman’s reproductive rights are exchanged for her maintenance,” p. 183).

Duderija cites a publication by an Indonesian progressive think tank, Fahmina (Hadith and Gender Justice: Understanding the Prophetic Traditions, by F. Qodir – unfortunately I couldn’t find any trace of it online). This provides an example of how a growing number of Muslims worldwide are rethinking the traditional Islamic legal norms relative to marriage:

The Qur’an has outlined several principles that guarantee the achievement of successful marriage. One of these requires that a husband-wife relationship ought to be joint or two-way relationship in which one side is equal to the other. In such as [sic] even and equal relationship, one side acts as a companion who completes the other, with no superiority or inferiority issues involved. The picture of such a harmonious and parallel relationship of husband and wife is portrayed in an extremely beautiful poetic language by the Qur’an as in “your wives are a garment for you and you are a garment for them (Al-Baqarah, 2:187).

3. Concept of the text’s moral trajectory: if you look at qur’anic injunctions regarding women in the context of its time, you will notice a divine design going far beyond that particular socio-historical context. The principles of equality, justice and love are enunciated in the text and the specific guidelines that are given clearly correct some of the worst practices of the time – for instance by forbidding female infanticide, by guaranteeing female property rights, and so on. But one shouldn’t stop there. God couldn’t drastically change those cultural practices in one blow. He’s a gracious pedagogue who knows that change among humans can only be best achieved in a progressive manner. So he gives each new generation the responsibility to transform the social order more and more in conformity with the ideals revealed in the sacred text. In Abou El Fadl’s words,

The thorough and fair-minded researcher would observe that behind every single Qur’anic revelation regarding women was an effort to protect the women from exploitative situations and from situations in which they are treated inequitably. In studying the Qur’an it becomes clear that the Qur’an is educating Muslims how to make incremental but lasting improvements in the condition of women that can only be described as progressive for their time and place” (quoted on p. 184).

I’ll stop here, hoping that if this is a topic you find interesting, you will do more reading on your own – starting with Duderija’s book! Here's an excellent summary on Islamic feminism by one top scholar, Margot Badran. Also, I have dealt with the issue of religion and patriarchy from a wider angle in three blogs, showing that gender issues are a challenge to people of all faiths today. Finally, in “resources,” I went into much greater depth exploring the theology of the most controversial of Muslim feminists, Amina Wadud.

More than anything, however, my hope is that in taking our lesson from Duderij’a’s important book, you have grasped how crucial hermeneutics are in reading sacred texts and thus in shaping one’s theological orientations. Indeed, hermeneutics go a long ways in explaining why Salafis and progressives seem to be living in different worlds.

This is the first of two blogs based on my review of Adis Duderija’s book, Constructing a Religiously Ideal “Believer” and “Woman” in Islam: Neo-Traditional Salafi and Progressive Muslims’ Methods of Interpretation (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

Duderija picked two Islamic movements that are polar opposites. OK, so the jihadis are more extreme than the Salafis, but only because of their recourse to violence as the means to establish God’s reign on earth. Nevertheless, their way of reading and interpreting the Qur’an and Sunna are very similar. Just keep in mind that as within any religious movement there are multiple factions and nuances (see my blog about Salafis).

On the other end, you can find many “secular Muslims,” that is, non-practicing but still tied to the cultural trappings of their Muslim upbringing, and handfuls of free-thinking Muslims who work hard at keeping their “heretical” views under the radar, who are more liberal than “progressive Muslims,” the topic of the next blog.

So in the middle you have this hodge-podge of “mainstream Muslims,” a term impossible to define unless you point to a particular country and a particular socioeconomic context. That said, one good indication of what majorities of Muslims think on a variety of issues comes from the 2008 book based on a very extensive Gallup Poll in over 35 different Muslim nations (Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think, John Esposito and Dalia Mogahed, eds., Gallup Press).

Duderija’s postmodern methodology

For Duderija and many other progressive Muslims, “late modern” or postmodern theories of hermeneutics (how texts are read and interpreted) give us the best tools to study religion and the people that subscribe to them. In this vein, “theology” (how we construe God to be and how humans are supposed to relate to him, her or it, if you’re Buddhist) is “constructed” by “communities of interpretation.”

By the way, this was very much the perspective I used in my book, Earth, Empire and Sacred Text. Here’s how I defined theology in the Introduction:

“an ever-growing and evolving reflection—in the light of sacred texts and in interaction with a specific religious tradition—that leads people to better articulate their relationship to God, provides answers to the ultimate questions of human existence, and gives shape to a life-style in the world as community that best reflects that understanding. As such, theology must always be constructed within a particular socio-political, historical and cultural situation.”

In light of this, Duderija is looking at two very different schools of thought among Muslims and trying to dig up the theological and philosophical assumptions that make them interpret the sacred texts so differently. To simplify a bit – hopefully even to clarify his position, I hear him making three interconnecting points. As I put it in my review, Duderija uses three different lenses to highlight these two schools’ interpretive assumptions:

1) A theology of humanity, and in particular, what it means for humans to be God’s representatives or trustees on earth. Are they empowered by God with a moral compass enabling them to discern a righteous path based on the ethical imperatives of the texts amid the changing conditions of human societies? Or are they morally disabled, needing therefore to apply literally the teaching of the hadiths (like the early ahl al-hadith movement), or the body of rules laid out by the jurists of the classical period (Islam of the madhahib, or the various schools of Islamic law)?

2) A philosophical position on the status of the good: first, an ontological statement – is an act good in and of itself (ethical objectivism), or is it good only because God commands it (ethical voluntarism)? Then an epistemological statement, connecting to the first lens: can humans access that knowledge in the first case? In the second case, by definition, this knowledge cannot be attained apart from revelation.

3) A philosophical position on the status of language and meaning production: all premodern (and even modern) views proffer a positivistic view of language. Its external signs, from philology to syntax to grammar, represent an absolute and immutable signifier that, if carefully adhered to, yields for every reader of every place and time the same meaning. Starting with the 19th-century Romantic thinkers and the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher language became identified with the human being in history. In other words, a significant gap appeared between historical events and the language used to depict them – a gap, I would add, which grew wider with the work of 20th-century philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, and even more so with postmodern theorists like Michel Foucault, Stanley Fish, Richard Rorty and Edward Said.

What’s behind the Salafi method of interpretation?

For the sake of space, I’ll address this question in bullet form. A useful complement to this, and particularly the Salafi view of history and their own evolution over time, see my blog, “Whence the Salafis?”

1) The Salafi version of “true Islam” is rooted in their particular Sunni vision of early Islam. In fact, this is not only true of Sunnis versus Shia, but also of groups like progressive Muslims. This is so because the Prophet Muhammad ruled only ten years in Medina (622-32) and the four Companions who succeeded him in Medina (the so-called “Rightly Guided Caliphs”) were all assassinated, except for the first one, Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s father-in-law, who died two years after Muhammad himself. There was a great deal of turmoil in the first sixty or so years of the early Muslim community and the way one chooses to tell the story hugely impacts one’s theological orientation.

The Salafis derive their name from the Arabic “al-salaf al-salih” (the righteous forbears), who naturally include all the Prophet’s Companions (as a title it’s always capitalized), some from the next two generations and a select few scholars over the ages, almost all of them harking from the Hanbali school of Islamic law (Saudi Arabia being the only country where it’s the official ideology in tandem with its 18th-century revivalist version, Wahhabism).

All these salaf are “righteous” – for one specific reason: they are the people who collected reports about what the Prophet said and did (hadith) and, as many of you know, the two sacred texts of Islam are the Qur’an and the Sunna (the Prophet’s righteous model that all believers are called to emulate as much as possible in their own lives). For the Salafis, the Sunna IS the body of hadiths that have been sifted and authenticated in the six main collections (with three others often referred to as well) and they are the direct heirs of the early movement to collect these hadiths in all corners of the Islamic empire in its first two centuries. These pious individuals are collectively called ahl al-hadith (“the people of hadith”).

2) They are primarily focused on the hadiths (in their view Sunna), secondarily on the Qur’an. For them any hadith in the official, semi-canonical collections clarifies, amplifies and settles the meaning of the Qur’an – not the other way around.

3) For them, the meaning of these texts is both clear (to any reader in whatever age or context) and attached to the letter itself. No need for any theory of interpretation, they say. Just do what the text says. This is theological literalism or textualism. It’s the position that most rules out any role for human reason. Humans don’t know right from wrong, even though they think they do. They need revelation, which God has made available in great detail for questions of daily life.

In philosophy, as mentioned above, it’s called “ethical voluntarism”: an act is good only because it is commanded by God. Being kind to one’s neighbor is only good because either you find it commanded in the Qur’an or in the body of hadiths. Of course, this is an extreme position, and in fact Islamic law as it developed in its various schools in the classical period (10th-13th centuries CE), was more flexible than that. And that’s the point: the Salafis condemn the jurists of the schools (ahl al-madhdhahib, “people of the schools of law”) for using too much human reasoning in their development of the law. Tools such as qiyas (analogical reasoning) or considerations of maslaha (public good) are actually tools of the devil. They draw you away from what God and his Prophet commanded.

4) Theirs is an ahistorical reading of the texts. By this I mean that the detailed admonitions and advice given by God in the Qur’an and the Prophet during his 22-year ministry (the hadiths) was not just addressed to a 7th-century Arab Bedouin audience but to people of all times. There is no contextualization of the message whatsoever here, and no distinction between the letter and the spirit of the law.

There are many other points I could make, but I just want you to get the main idea. My last two sections are the most interesting (though you need the first two to make sense of the whole), as they give you two fascinating case studies – what the Salafis teach about salvation and women.

The Salafi “ideal believer”

Whereas the qur’anic data can seem to point either to pluralism (sincere Christians and Jews will go to heaven) or to exclusivism (only Muslims – and the “right” kind – are saved), the hadiths are almost totally on the exclusivist side of the spectrum. So instead of seeing the qur’anic passages which are especially harsh on the Jews as a reflection of the very real political tensions between the Muslims and the Jewish community when Medina was at war with Mecca, any and every verse applies to the Jews at all times.

Let me give you three examples of hadiths on this topic:

“Narrated Abu Hurayra: ‘Suhayl ibn Abu Salih said: “I went out with my father to Syria. The people passed by the cloisters in which there were Christians and began to salute them.” My father said: ‘Do not give the salutation first, for Abu Hurayra reported the Apostle of Allah (peace be upon him) as saying: Do not salute them (Jews and Christians) first, and when you meet them on the road, force them to go to the narrowest part of it’” (Abu Dawud collection, 5186).

“Narrated ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Umar: ‘Allah’s Apostle said, ‘You [i.e., Muslims] will fight with the Jews till some of them will hide behind stones. The stones will (betray them) saying, O ‘Abd Allah [i.e., slave of Allah]! There is a Jew hiding behind me; so kill him’” (Bukhari collection, 4.176).

“Narrated Abu Hurayra: ‘The Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him) observed, “By Him in Whose hand is the life of Muhammad, he who amongst the community of Jews or Christians hears about me, but does not affirm his belief in that with which I have been sent and dies in this state (of disbelief), he shall be but one of the denizens of Hell-Fire”” (Muslim collection, 284).

As it turns out, this mistrust and even hostility toward members of other faiths also stems from a particular Salafi doctrine called al-wala’ wa-l-bara’ (loyalty and severance). In a nutshell, it involves surrounding oneself with “true” believers and shunning all unnecessary contact with those outside. A contemporary Salafi writer, Qahtani, puts it this way:

“When Allah granted love and brotherhood, alliance and solidarity to the believers He also forbade them totally from to [sic] allying themselves with disbelievers of whatever hue, be they Jews or Christians, atheists or polytheists” (Duderija, p. 92-93).

From a sociological perspective this “enclave mentality” is typical in many religious communities of various faiths in our age of globalization – “it’s us the true believers against a hostile world.” For more detail on this see my blog on fundamentalism.

The Salafi “ideal woman”

Duderija indicates three important assumptions both Salafis and classical Muslim jurists brought with them in pondering this question. It’s important therefore to note that most of the following is common to the traditional writings of the jurists in their various schools as well as to the more puritanical Salafis today. These assumptions fall in three areas:

1. The nature of female (and male) sexuality: males and females are essentially different and their differences revolve around their sexuality. Male superiority over the female is both ontological and sociomoral – the man is more intelligent than his female counterpart, and more capable of leadership and wise ethical judgment. But the assumption with the most consequences for Muslim societies is sexual in nature: the female body is morally corrupting for men who find women impossible to resist. Here is Duderija interacting with the work of Moroccan sociologist Fatima Mernissi (she will reappear in the next blog):

“On the basis of classical Muslim literature she argues that Muslim civilization, unlike the modern Western one, developed an active concept of female sexuality regulating female sexual instinct by ‘external precautionary safeguards’ such as veiling, seclusion, gender segregation, and constant surveillance. What underpins this view is the ‘implicit theory’ based on the notion of the woman’s kayd power, that is, the power to deceive and defeat men, not by force but by cunning and intrigue. This theory considers the nature of woman’s aggression to be sexual, ‘endowing [the Muslim woman] with a fatal attraction which erodes the male’s will to resist her and reduces him to a passive acquiescent role.’ As such women are a threat to a healthy social order (or ummah), which, as we shall subsequently see, is conceptualized as being entirely male” (Duderija, pp. 101-102).

The following two hadiths stress the danger that women pose to society:

“Abd Allah b. Masood narrated that the Prophet said, ‘[The whole of] the women are ‘awra [first meaning is “deficiency” and second meaning applicable here is “female genitals” – a good example of how language reflects culture] and so if she goes out, the devil makes her the source of seduction.’”

“Abd Allah b. ‘Umar narrated that the Prophet said, ‘I have not left in my people a fitnah [meaning ranges from temptation, enchantment and infatuation to intrigue, sedition, and civil war] more harmful to men than women.’”

It is this category of hadiths that gives fuel to Salafi scholars to place all manner of restrictions on women. Shaykh Ibn Baz (1910-99) was an influential Saudi jurist and Saudi Arabia’s Grand Mufti for the last six years of his life. He was also a self-declared Salafi. Just to explain: all of the Saudi jurists, and especially those with some kind of official function, follow the Hanbali school of Islamic law, the most rigorous and literalistic of the four Sunni schools of law. These jurists are also Wahhabi, that is, giving allegiance to the puritanical movement of reform initiated by Muhammad b. Abd al-Wahhab (d. 1792), which has now become the kingdom’s official ideology (Wahhabism). But some Wahhabi clerics have also identified with the wider (and much more recent) movement called Salafism, which can tend to be even more puritanical and exacting in its rules than Wahhabism.

Ibn Baz leans on these kinds of hadith to say that women may not drive cars; that they may not sit privately with any man; not work with any men; not receive any visits from a man not in their family and not travel anywhere without a male-guardian. Concludes Duderija, “Thus, religiously ideal female Muslim identity, as we will argue subsequently, would be constructed along the lines of their complete ‘invisibility’ in the public domain of males” (p. 105).

2. Women and the public sphere: as mentioned in the last sentence, classical Islamic law and certainly Salafis today impose a number of rules and regulations limiting women’s social participation, including the religious obligation of hijab (headscarf, but also requiring a modest, form-covering shawl over the rest of the body), niqab (some kind of veil covering the face; in typical Salafi fashion women are totally covered in black, including gloves), segregation of the sexes and seclusion of women in particular.

On that last point, here are two hadiths to support that view:

“Narrated by Abd Allah b. ‘Umar that the Prophet said, ‘The prayer of a woman in her room is better than her prayer in her house and her prayer in a dark closet is better than her prayer in her room.’”

Narrated by Abu Bakrah, the Prophet is reported to have said, ‘Those who entrust their [sociopolitical] affairs to a woman will never know prosperity.”

Here I have to interject: in the picture on top of this page you have a Salafi couple, but you know for sure this picture could not possibly have been taken in the Muslim world, and certainly not in the Arabian Gulf countries. There couples would never have any physical contact in public (even holding hands); the man would likely be walking ahead of his wife; there would never be any display of affection in a public place. This is Europe, and in light of the article, I would guess Germany. Read these two women’s stories – how they were transformed from club hopping socialites with a string of male relationships to becoming deeply satisfied (from what they say) Salafi wives, by way of a born-again like experience.

3. Marriage and spousal rights: “the premodern Islamic jurisprudence developed a system of sharply differentiated, interdependent, gender-based spousal rights and obligations” (p. 103). Duderija leans on a book by Kecia Ali, Associate Professor of Religion at Boston University (a progressive Muslim), to say that “marriage, in essence, was a type of ownership (milk) based upon a contract between the parties giving rise to mutually dependent gender-based rights and obligations.” The key word here is “ownership” – the context, let’s not forget is a patriarchal society with sharp social stratification built on slavery. Here is a longer quote that is mostly taken from Ali’s book, Sexual Ethics and Islam: Feminist Reflections on Qur’an, Hadith and Jurisprudence:

“At the core of this contract was a transaction whereby a wife’s sexual availability was exchanged for her right to be financially supported and maintained by her husband. Furthermore, she states that ‘at its most basic, the [classical] jurists shared a view of marriage that considered it to transfer to the husband, in exchange for the payment of dower, a type of ownership (milk) over his wife, and more particularly over her sexual organ (farj, bud’).’ Based on this concept of marriage, women’s constant obligation to be sexually available to her husband resulted in granting to her husband a total control over his wife’s mobility so much so that it could prevent her from going to the mosque, family, visiting her parents, or even from attending the funeral of her immediate family, including her parents and children. This view of marriage, in addition to other laws pertaining to divorce and child custody, and the strictly associated gender differentiated marital rights and obligations, resulted in the creation of a hierarchical, authoritarian marital relationship and the creation of a classical Islamic tradition based on male epistemic privilege” (p. 103).

Now that you see those three areas of assumptions clearly spelled out, you can imagine where that mindset focused on a literal application of hadiths might lead Salafi clerics. Whereas Muslim countries, particularly in the postcolonial period, have made great strides to mitigate the worst of this legal framework so as to promote the participation of women in all sectors of society (recall that six Muslim-majority countries have had female heads of state), there has also been a growing tide of conservative religiosity in Muslim circles as happened among other faith traditions since the 1970s. This of course – combined with all the instability and wars in the Middle East and Central Asia, and especially the impact of Saudi petro-dollars used to spread the Wahhabi gospel to all continents – has been fertile ground for the growth and spread of Salafi-like doctrines and practices.

How do progressive Muslims counter this textualist and unabashedly patriarchal reading of the Qur’an and Sunna? That will be the topic of my next blog.

Still, I can’t close on this rather somber and depressing picture of men and women. Just a week ago, a young Saudi comic, shortly back from his university studies in the USA, decided to register his own satirical protest against the Saudi ban on women driving in a song that went absolutely viral on the internet.

Just two things you need to know: Wahhabis forbid musical instruments and one Wahhabi/Salafi shaykh gave a fatwa saying that driving could make women infertile. Read too this short commentary in a British paper; then watch it again and laugh! When the youth rise up with such creativity, humor, and insight, you know that change is in the air!

70 percent of Jews agree with 92 percent of Muslims that American Muslims have no sympathy for the jihadists – that was one of the findings from a 2011 Gallup Poll report called, “American Muslims: Faith, Freedom and the Future.” What is more, large majorities of American Jews and Muslims (roughly both six million) agree on the necessity of finding a two-state solution to the Mideast crisis.

That unexpected common ground between the two communities of faith was one of three rather surprising conclusions of that poll. In this second half I would like to discuss some of the challenges the US Muslim community faces in the coming years. Three challenges came out in the course of the previous blog:

a) The Muslim population is much younger than that of other faiths in America. A related challenge as second and third generations come of age is how the religious establishment – in its many different currents – can find ways to keep them religiously educated and spiritually involved.

A Philadelphia paper ran an AP article about a 31-year-old imam, Mustafa Umar, who works specifically with the younger generation at the Islamic Institute of Orange County in Southern California. He is especially well equipped for that task, as he’s a native Californian savvy in the use of social media and a trained Islamic scholar in Europe, the Middle East and India.

When you consider that the great majority of imams in the USA are foreign-born, you begin to wonder how these mosques will be able to retain any hold on the children of these immigrants who grow up in a very free and secular society.

Philip Clayton, provost at Claremont Lincoln University (the first interreligious seminary in the US) now has a program to train Islamic leaders. Clayton puts this challenge pointedly: Mosques that remain insular, focus on ethnic identity, and don't engage with the realities of being Muslim in America won't survive, he said. And the more engaged imams and mosques become, the less likely confused youth are to turn to radicalized forms of Islam, the way the Boston marathon bombing suspects did.

b) On average the Muslim population is poorer than their religious counterparts. This flies in the face of what the famous imam of the Manhattan mosque, dubbed Park 51, Feisal Abdul Rauf, wrote in a 2011 article entitled "Five Myths About Muslims in America." One of the myths he seeks to debunk is that “Muslims are ethnically, culturally and politically monolithic.” That, we know from the recent Gallup poll could not be farther from the truth.

But then he adds that "Muslims are an indispensable part of the U.S. economy. Sixty-six percent of American Muslim households earn more than $50,000 per year — more than the average U.S. household.” Earlier he had been quoting from a 2007 Pew Poll. In any case, what is clear from the more recent poll is that there is a quite a gap in incomes between some of the more recent South-Asian immigrants and some of the other Muslim communities – the difference between the urban poor and the suburban middle and upper-middle class.

Omid Safi, who I introduce in greater detail later, lists this as the very first challenge of the Muslim community in the US:

“The first is overcoming the divide between immigrant and African American communities. It remains to be seen how much unity can be forged between the immigrant Muslim population in America and the African American Muslim population. There are profound class divisions between the two, which often dictate communal, social, and political participation.”

c) Finally, the 2011 Gallup Poll revealed a latent distrust among Muslim Americans of the organization meant to represent them. A 2006 special report by the US Institute of Peace on “The Diversity of Muslims in the United States” (find it here) offers a great list of American Muslim organizations in three categories – religious and interfaith, civic and political, legal organizations. In the Gallup Poll the front runner was clearly the (civic and political) Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), followed by the (religious) Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), and then the (civic and political) Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC).

By the way, CAIR must be doing something right . . . Its Philadelphia chapter (one of 20 nationally) is led by a Jew!

I will now be listing three more challenges as seen through the eyes three Muslim American leaders.

1. For Muslims, and especially the more recent immigrants, to invest in the American political structures. The Iranian-American scholar Omid Safi, Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, contributed as co-editor and writer to the 5-volume Voices of Islam. In the fifth volume (Voices of Change) he has an essay entitled, “I and Thou in a Fluid World: Beyond ‘Islam versus the West.’” This is the second challenge he puts forth, particularly for the Muslim immigrants:

“Many came to this country for the same reasons that other immigrants have: the pursuit of a better life, the promise of freedom, and so on. Yet at least the first generation of immigrants have often looked back toward their origin as their real ‘‘home’’ and have not fully invested monetarily and emotionally in American political and civic structures. Many immigrant Muslims have led lives of political neutrality and passivity, seeing their primary mission as that of providing for their families. There are, however, signs that this political lethargy is beginning to change in the charged post-9/11 environment, particularly among the second-generation immigrant Muslims.”

I will come back to Omid Safi in a subsequent blog, as he’s a leading voice in "progressive Islam." I used a Friday sermon he gave at a Duke Friday Prayers service in on online course on Islam recently with great effect. You can see why Muslim students, at least the not-too-conservative ones, love to listen to him. My Christian students too found him refreshing and at some level were able to relate to his theme of “what would Muhammad do?”

2. Continue the work of empowering women. Feisal Abdul Rauf is the imam of the famous al-Farah mosque in Manhattan which after 28 years moved to its Park51 location near Ground Zero. More than that, Abdul Rauf and his wife Daisy Khan are high profile leaders in interfaith dialog in the US and many other parts of the world. They lead two influential organizations, the Cordoba Initiative and the American Society for Muslim advancement (ASMA). Khan herself also founded Women’s Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality (WISE) and constantly travels, speaking and organizing Muslim women conferences.

A frequent contributor to the Washington Post and other media outlets, Abdul Rauf posted a piece in 2011 that directly relates to our topic, "Five Myths about Muslims in America." The third myth he chose to debunk was that “American Muslims oppress women.” Now keep in mind that such an article is, by definition, apologetic. He is attempting to rebut a common accusation about Muslims in general. So his first paragraph highlights America’s female movers and shakers: