-

-

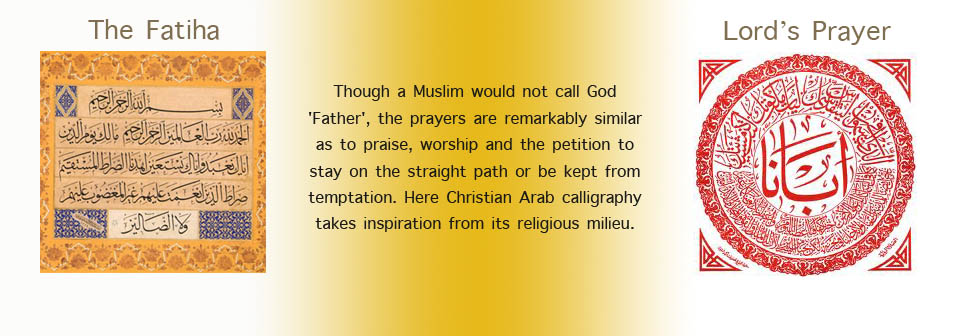

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

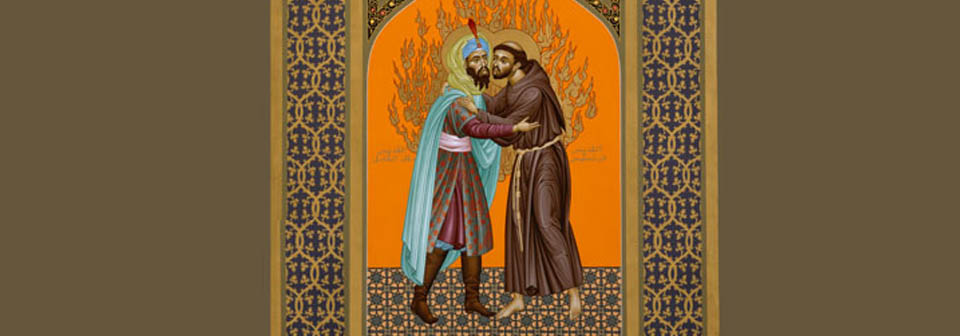

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

[This is the second blog in a Lenten series on poverty]

In the first installment on poverty I argued that from a Muslim and Christian perspective the scandalous economic inequalities we now witness in our world can only be tackled with a holistic approach: short term relief for victims of hunger and natural disasters and long term pressure on the powers-that-be, locally and internationally, to redress structural injustices. Here I use the USA as a case study, and more specifically a recent debate in the media and among top policy analysts.

One of the fallouts of the “Great Recession” is a national shouting match over rising inequality, never more eloquently portrayed than by the Occupy movement’s slogan, “we are the 99%.” But lost in the shuffle is the changing nature of poverty in America. It’s getting worse and the old clichés about poverty and race are now questioned. In fact, according to New York Times columnist and respected writer/activist on behalf of the world’s poorest, Nicholas Kristof, the white working class now risks being “locked in an underclass."

Kristof was writing about the release of Charles Murray’s book, Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010. Murray is a scholar for the staunchly conservative American Enterprise Institute and, unsurprisingly, his book was cheered on the right and booed on the left. Yet it did spark a needed debate about a sobering phenomenon.

Shockingly, I ask myself, did it take the realization that a number of whites were joining the throngs of blacks, Latinos and Native Americans already overrepresented among the fifteen percent under the poverty line to start a national conversation about poverty? Meanwhile, racist structures continue to make it more likely for people of color to be poor. How else can you explain that 70% of the US prison population is non-white? But that’s another topic.

Nevertheless, the stormy debate generated by Murray’s book highlights important issues about poverty in the US. Among the "Five Myths about White People." Murray offers in a Washington Post article published just before his book’s release, I choose to discuss three:

1. Working class whites are more religious than upper-class whites – wrong, he says, for “nearly 32 percent of upper-middle-class whites ages 30 to 49 attended church regularly, compared with 17 percent of the white working class in the same age group.”

2. White working-class men have a strong work ethic – wrong again: numbers have been growing fast for working-class men giving up on full-time work or any work at all.

3. Marriage is breaking down throughout white America. Overall, this is true, but among whites, “there is a sharp class divide on marriage.” A high school education turns out to be the watershed – he defines “working class” as those with a GED or less. He explains:

"The share of upper-middle-class whites ages 30 to 49 who are married has been steady since 1984, hovering around 84 percent. During that same period, marriage for working-class whites in the same age group has fallen from 70 percent to 48 percent . . . Marriage now constitutes a cultural fault line dividing the socioeconomic classes among white Americans."

For Murray all three are the result of liberal social welfare policies and declining moral/religious values. Admittedly, these are complex issues; yet I make two points with confidence in this blog. First, Murray’s analysis is flawed because incomplete; and second, applying Christian values (which are overwhelmingly shared by Muslims and Jews) could help bring lasting solutions to poverty in America.

Poverty – with or without “values”

I will start with Murray’s commentary on the second myth – that white men with at most a high school education have lost their strong work ethic. His figures are striking:

“In 1968, 97 percent of white males ages 30 to 49 who had at most a high school diploma were in the labor force — meaning they either had a job or were actively seeking work. By March 2008 (before the Great Recession), that number had dropped to 88 percent. That means almost one out of eight white working-class men in the prime of life is not even looking for a job.”

Murray naturally excludes post-2008 figures, because his argument is that this is a systemic problem – I will argue that too, but from a different viewpoint. For him it’s caused, on the one hand, by too many government handouts; and on the other, by declining family values. Fewer and fewer men stay married and those who are seem to care less about providing financially for their families. Solid marriages are indeed a poverty buster. I’m less impressed with the failure of government programs.

But is this an issue of values? More plausibly, loss of family values could be the result, rather than the cause, of vanishing economic opportunities, especially in view of the fact that middle and upper middle-class white males seem just as religious (and married) as before. Indeed, there is more to the picture than Murray admits. Here are some figures Princeton economist and Nobel laureate Paul Krugman offers, as he argues that most of this white underclass phenomenon can be attributed to “a drastic reduction in the work opportunities available to less-educated men”:

“Adjusted for inflation, entry-level wages of male high school graduates have fallen 23 percent since 1973. Meanwhile, employment benefits have collapsed. In 1980, 65 percent of recent high-school graduates working in the private sector had health benefits, but, by 2009, that was down to 29 percent.”

Back to Kristof, who has no trouble identifying with this problem on a personal level:

“My touchstone is my beloved hometown of Yamhill, Ore., population about 925 on a good day. We Americans think of our rural American heartland as a lovely pastoral backdrop, but these days some marginally employed white families in places like Yamhill seem to be replicating the pathologies that have devastated many African-American families over the last generation or two.

One scourge has been drug abuse. In rural America, it’s not heroin but methamphetamine; it has shattered lives in Yamhill and left many with criminal records that make it harder to find good jobs. With parents in jail, kids are raised on the fly.”

As you would imagine, this pattern wreaks havoc with families:

“Then there’s the eclipse of traditional family patterns. Among white American women with only a high school education, 44 percent of births are out of wedlock, up from 6 percent in 1970, according to Murray.”

Kristof agrees with Murray that “solid marriages have a huge beneficial impact on the lives of the poor (more so than in the lives of the middle class, who have more cushion when things go wrong).” In fact, research has shown a correlation between healthy marriages and a decrease in substance abuse and crime:

“One study of low-income delinquent young men in Boston found that one of the factors that had the greatest impact in turning them away from crime was marrying women they cared about. As Steven Pinker notes in his recent book, “The Better Angels of Our Nature”: “The idea that young men are civilized by women and marriage may seem as corny as Kansas in August, but it has become a commonplace of modern criminology.”

Having conceded this, however, he rejoins Krugman in saying that employment is crucial in the overall mix:

“Jobs are also critical as a pathway out of poverty, and Murray is correct in noting that it is troubling that growing numbers of working-class men drop out of the labor force. The proportion of men of prime working age with only a high school education who say they are ‘out of the labor force’ has quadrupled since 1968, to 12 percent.”

So we’re piecing together the strands of a more comprehensive explanation for soaring poverty rates: family values do matter – and as a person of faith I’ll add “spiritual and moral values” – but there are systemic injustices on the macro level that are forcing more and more people under the poverty line and keeping them there. This is above all a moral issue. It’s about the shameful fact that in the richest and most powerful country of the world poverty has steadily worsened over the last few decades (for a more in-depth rebuttal of Murray’s position see Jared Bernstein’s “Charles Murray’s Coming Apart”).

Old prophets and new ones

The Old Testament prophets blasted out God’s judgment on his wayward people. The eighth-century BC prophet Amos sent from Judah to the northern Kingdom of Israel based in Samaria is one among many others calling the Israelites to repentance. With great courage he intones,

“Come back to the LORD and live! Otherwise, he will roar through Israel[a] like a fire, devouring you completely …

You twist justice, making it a bitter pill for the oppressed.

You treat the righteous like dirt …

You trample the poor, stealing their grain through taxes and unfair rent …

For I know the vast number of your sins and the depth of your rebellions.

You oppress good people by taking bribes and deprive the poor of justice in the courts” (Amos 5:6, 7, 11, 12).

God singles out the elites, who misuse their power to trample the poor and enrich themselves at their expense, and he calls them to account.

I have long been a fan of the Rev. Jim Wallis, a contemporary prophetic voice who founded Sojourners about forty years ago – both a journal and a Washington, DC-based Christian community. His 2005 book (God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It) has a chapter that speaks to the issue of poverty in America. At one point he writes,

“The truth is that hungry people are going without food stamps, poor children are going without health care, the elderly are going without medicine, and schoolchildren are going without textbooks because of war, tax cuts, and a lack of both attention and compassion from our political leaders. The deepening injustice of America’s domestic policies is increasingly impossible to justify. It’s becoming a religious issue” (p. 222).

Wallis argues for a multi-pronged attack on poverty drawing on “the insights and energies of both conservatives and liberals” (p. 226). We shouldn’t just look to government, or the market, or churches and charities; we should especially focus on learning new ideas from grassroots projects that are actually working across the country. Indeed, we have to be committed to those conservative values of personal and moral responsibility, as well as family values. But we also can’t forget those hard-working poor that simply could never pull their families out of poverty considering their meager salaries and lack of benefits. And there’s more:

“Overcoming poverty … entails better corporate and banking policies and effective government action where the market has failed to address fundamental issues of fairness and justice” (p. 228).

During the 2004 election year at Pentecost Wallis gathered Christian leaders in Washington, “evangelical and mainline, Catholic and Protestant, black, Hispanic, Asian, and white, making a common declaration across the theological and political spectrum of the church’s life.” The outcome was a “Unity Statement on Overcoming Poverty,” which in its last paragraph reads,

“We therefore covenant with each other that in this election year, we will pray together and work together for policies that can achieve these goals. We will ensure that overcoming poverty becomes a bipartisan commitment and non-partisan cause, one that links religious values with economic justice, moral behavior with political commitment. We will raise this conviction in the public dialogue, and we will seek to hold all our political leaders accountable to its achievement” (p. 240).

Another evangelical prophetic voice is that of Ron Sider, founder of Evangelicals for Social Action, and author of the 1977 classic book, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger. He has just penned a new book examining the federal deficit in parallel with the fact of growing poverty. It is aptly titled, Fixing the Moral Deficit. I have no space here to comment on it here, but I can offer a good review of the book in Sojourners.

The last contemporary “prophet” I want to highlight, is David Beckmann, a Lutheran pastor who worked for fifteen years with the World Bank, overseeing large-scale development projects, while constantly applying innovative means to reduce poverty. Then in 1991, he became president of Bread for the World, a Christian, bipartisan organization aiming to eradicate hunger in the US and around the world, including its research arm, Bread for the World Institute. “Bread” mobilizes people in the church and organizes campaigns that bring hunger and poverty to the attention of policy makers in Washington and abroad.

Laureate of the World Food Prize in 2010, Beckmann has been asked to testify in Congress eighteen times so far. Among Bread’s achievements in the last decade:

“Due in part to the persistent, bipartisan advocacy of Bread members, the U.S. government has tripled funding for effective programs to help developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Bread has also helped double funding for U.S. nutrition programs, assisting millions of families in the United States who struggle to feed their children. Recently, Bread for the World initiated a campaign to press Congress to reform U.S. foreign aid to make it more effective in reducing hunger and poverty, and another to protect and strengthen tax credits for low-income working families.”

According to their website, "14.5 percent of households struggle to put food on the table. More than one in four children is at risk of hunger." What is more, 15.1 percent of the American population lives in poverty. Bread for the World strongly believes that hunger is the only direct cause of poverty and therefore sees three main solutions for US hunger eradication:

1. Child nutritional programs: “Child nutrition programs—school lunches and breakfasts, summer feeding programs, and the Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program—are critical to ending childhood hunger. When children receive the nutrition they need, they are more likely to move out of poverty as adults.”

2. Good jobs: along with benefits that will help hard-working people to climb out of poverty.

3. Work support programs: this includes the Earned Income Tax Credit (tax breaks for the poor) and the child nutritional programs.

Poverty leads to hunger. When childcare, rent, transportation and utilities are paid, low-income families cut corners on food. Somehow a tax system that reduces the burden of the less fortunate, federal and state funded poverty alleviation programs, laws that help in various ways to ensure a living wage, and laws that facilitate entrepreneurship as well as the growth of US manufacturing – all of this and more is necessary to help America eradicate poverty and hunger. Soup kitchens, food coops, and the host of existing nongovernmental (secular or faith-based) charities are needed but can never even come close to solving a national problem that is fundamentally about structural injustice and oppression.

Values and poverty eradication

Is poverty increasing because values are eroding, as Murray claims? Yes, but those whose moral values are eroding include all of us – the poor, and to a larger extent, the other citizens who are complicit in a system that beats down the poor. Then too, the values that count when it comes to overcoming poverty are primarily compassion and love for one’s neighbor in need, and passion for justice and righteous living. And yes, strong, caring families remain the foundation of a healthy society.

Interestingly, David Beckmann also founded the Alliance to End Hunger, which includes 75 members, “corporations, non-profit groups, universities, individuals, and Christian, Jewish and Muslim religious bodies.” Indeed, these are values that all people of faith can build on together. No doubt it will take the concerted will and persistent efforts of all people of faith (and non faith) to overcome extreme poverty – starting in America.

The Hebrew Bible – or the Christian Old Testament – begins with God creating the world in six days. On the sixth, after bringing forth all the animals, God created human beings in his image, both male and female. Then in verse 28 of Genesis 1 we read:

“Then God blessed them and said, ‘Be fruitful and multiply. Fill the earth and govern it. Reign over the fish in the sea, the birds in the sky, and all the animals that scurry along the ground.’”

In this creation story God imparts to humanity the mission to “rule” over the earth and its creatures. The common word used by Christians for this is “stewardship,” meaning Adam and Eve and their descendants remain accountable to God for the way in which they manage the affairs of the earth.

In a similar way, the Qur’an teaches that Adam was placed on earth as God’s “caliph” – a word also used for the political successors of Muhammad in seventh-century Arabia. But the word connotes authority as well, as the caliphs were empowered to rule in the Prophet’s stead. But more importantly, in the context of this verse in Q. 2:30, Adam is called to be God’s steward and trustee, ruling with wisdom over the creatures under him. For only he and his kind are given “the names of all things,” an expression that commentators have tied to humankind’s ability of reason and moral discernment.

I recently wrote about the environmental dimensions of humanity’s trusteeship on earth. Here I begin a series on faith and poverty, spurred on by a Lenten program at my church focused on the poor. In a blog about Fair Trade, I explored some of the complexities of the notion of poverty, emphasizing in particular the unjust structures of global trade that hinder the economic development of the poorest countries. I’ll come back to the idea of structural injustice in another blog, but from a different angle.

A broad approach to eradicating poverty

Poverty is no mere academic discussion. It is achingly real, and what the World Bank calls “extreme poverty” (living below $1.25 a day) affects 1.29 billion people worldwide, which represents 22 percent of the developing world. According to the UN’s World Food Programme, hunger is the world’s top health risk and one in seven people go to bed hungry every day. If, as God made clear to Cain, we are “our brother’s keeper,” this should alarm us. After all, stewardship of creation includes caring for our fellow humans too.

My main point in this blog will be to stress that as people of faith, both Christians and Muslims, God calls us to face this issue head on from both the macro level (thinking about the poorest of the poor worldwide) and the micro level (what we can do locally). God also expects us to work simultaneously on long term solutions, tackling systemic injustices globally, nationally and even locally; and on short term poverty alleviation, that is, assisting victims of floods, earthquakes and other natural disasters.

Large relief and development organizations seek to work at both ends of this spectrum: providing urgent care for refugees, for example, but also finding ways to provide education for the children, coaching for the mothers, professional training for women and men – and all this while seeking to facilitate their transfer to a more stable and long term setting.

Though Muslims and Christians work with similar texts on the issue of creation, their traditions highlight different aspects of the “righteous society.” Still, both faiths historically have impelled their adherents to care for the poor in a holistic fashion.

An Islamic approach to poverty reduction

Just as there is no “Islamic” way to organize government (in spite of what many islamists might think), there is no one “Islamic” approach to tackle hunger in a twenty-first century nation-state. During the Cold War years, many Muslim scholars were prescribing some form of socialism. At the same time, oil-rich Gulf countries were eager to work with western nations, and apart from some of the strictures of “Islamic banking” (finding ways around the charging of interest), they developed economies that function seamlessly within the mechanics of global capitalism.

Still, giving to the poor is the heart of Islam. Muhammad was an orphan raised by his uncle and the Qur’an and hadith are full of exhortations to be kind to the widow, the orphan, the traveler in need, and the poor and oppressed in general. In addition, one out of Islam’s five pillars is zakat, the command to spend 2.5% of one’s net worth annually to help the indigent. It plays out in a variety of ways in Muslim societies and is not always applied literally, to be sure; yet there’s no denying this theme of compassion permeates Islamic spirituality and practice.

Ever since the Prophet ruled in Medina (622-632) as prophet and statesman, Muslims have believed that somehow piety had both a personal and communal – even political – dimension. So giving handouts to the poor was not sufficient. A just ruler had to make sure that the laws were fair and did not penalize the poor in any way. Likewise, the court system had to rule out injustice and corruption, so that both poor and rich could find justice.

Zakat has given rise to a multitude of private charities throughout the Muslim world, while at the same time Muslims expect a “godly” government to root out injustice and level the playing field in order for people of all social classes to earn a living with dignity. Social justice and compassion for the poor are key values in Islam – a fact that explains why many Muslims find the extreme economic inequalities within and between Muslim countries absolutely appalling.

Yet charity doesn’t stop with zakat for Muslims. The Qur’an enjoins them to give freewill offerings as well, or sadaqa – a word any student of Hebrew would recognize. In the second sura we read a thought similar to the teaching of Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount: “If you make public your free gifts, it is well. But if you conceal them and deliver them to the poor, that would be best for you, and will atone for some of your ill deeds. And God is well acquainted with all you do” (v. 271). In Jesus’ words, “don’t let your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (Mat. 6:3).

Finally, the ban on usury in the Qur’an, parallel to the one in the Law of Moses, is a structural mechanism designed to prevent the rich from exploiting the poor. Trade is an economic setup wherein investor and borrower share the risks of the venture. If the commercial deal succeeds, then both make a profit. If it fails, both share in the loss. By contrast, when a bank lends money to an entrepreneur with interest, any loss incurred will be borne solely by the borrower. As the Qur’an states,

“Those who gorge themselves on usury behave as one whom Satan has confounded with his touch. They say: ‘Buying and selling is but a kind of usury.’ But God has permitted trade and forbidden usury … God has blighted usury and blessed free giving with manifold increase. God loves not the impious lawbreaker” (Q. 2:275-276).

Ziauddin Sardar, whose book on the Qur’an I have examined in a blog recently (“God Consciousness and a Better World”), sees the recent economic meltdown in that light:

“We live in a time beset by the consequences of economic disasters. As we contemplate the results of subprime mortgages; the escalation in house prices which keeps increasing numbers of even moderately affluent people off the housing ladder; our economy fueled by an increasing debt burden on everyone; derivative trading that seeks to make money out of mis-selling to the poorest; increasing disparities between the pay of private employers and even the top management of public bodies as against the rest of the workforce; the billions paid in bonuses to those who manipulate the stock market to make money from money; there is pertinent cause for thought in this passage. Untrammeled consumerism has brought us a world of stark contrasts as well as an increasing gap between rich and poor. I see this passage as speaking directly to contemporary concerns” (Reading the Qur’an, p. 196).

A Judeo-Christian approach to poverty reduction

Many scholars believe that when Jesus at the outset of his ministry and in his hometown synagogue read from the Isaiah scroll, he was referring to the Year of Jubilee. Here’s the text from Luke 4:19-20:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

for he has anointed me to bring Good News to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim that captives will be released,

that the blind will see,

that the oppressed will be set free,

and that the time of the Lord’s favor has come.”

Besides the obvious reference to the poor as the main recipients of his ministry, as exemplified in his works of healing and exorcism, there is a wider context that only comes into focus with the last phrase, “the time of the Lord’s favor has come.” That’s the “Year of Jubilee” language.

The Jubilee came every fifty years, but it was part of a rhythm of work and rest – observing the seventh day as the Sabbath. Then, every seventh year (“Sabbath year”) all agricultural lands were to be left fallow and debts forgiven. Finally, after seven cycles of seven Sabbath years came the Year of Jubilee, during which not only were people to let the land rest; they were to forgive all debts once again and this time each property reverted to its original owner. Capital could not accumulate, nor could any kind of monopoly develop.

Leviticus 25, the major passage explaining the Jubilee, speaks of political and economic structural safeguards put into place so that wealth is fairly distributed among the people of Israel. Though it was rarely followed to the letter, this ideal of a righteous society tied to the redemption of the severely indebted and to the flourishing of the “least of these” (Mat. 25:40, 45) left its mark on both Jewish and Christian spirituality over the centuries. In fact, it was at the heart of American independence (Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell, “Let Freedom Ring!”), the Civil Rights Movement, and the Jubilee 2000 Campaign, initiated in the UK, that successfully put pressure on the World Bank and IMF to cancel the debts of the world’s poorest countries.

From the core of the Jewish, Christian and Muslim traditions, alleviating poverty is a holistic enterprise. Beyond the commands to give generously to the poor we find clear indications how we humans, as God’s trustees on earth, are called to organize our respective societies so that all members can flourish according to their own gifts and abilities. Some will naturally be richer than others; at the same time, the rich will be kept from beating down those weaker than themselves.

Examples of courageous faith-based initiatives to free people of various bonds and impediments continue to inspire, like the committed Christians who helped abolish slavery in nineteenth-century England. Today a plethora of Muslim and Christian relief and development agencies dot the globe delivering aid with compassion. What is more, people of faith are joining other more secular elements of civil society in many contexts to lobby for more justice for the poor and oppressed. That story in more detail is still to follow.

Last week I happened to see Newsweek’s cover article, “The Global War on Christians in the Muslim World,” and read it immediately. My reaction: like Ayaan Hirsi’s other writings, it is less than truthful. Most cited facts are indeed “facts.” But truth, surely, lies in a balanced telling of such life-and-death stories within their wider context. She does not.

Truth is, weaving a tale of Muslim rage with Christian victims piling up from Nigeria to Indonesia conveniently adds to the political strife of a US election year. When Democrats decry the plight of beleaguered Muslims, Republican hopefuls vie for the harshest invectives against Islamic radicalism. As it turns out, Hirsi Ali works for that great bastion of conservatism, the American Enterprise Institute.

When her bestseller “Infidel” came out in 2007, the Economist (clearly right of center) opined that for a woman who certainly “fascinates,” “the Dutch-Somali politician, who has lived under armed guard ever since a fatwa was issued against her in 2004, is a chameleon of a woman … Even the title of her new autobiography reflects her talent for reinvention." That is because it had first been published in the Netherlands as “My Freedom?” and that version was more focused on defending women’s rights. The new version is mostly about leaving behind the faith of her fathers.

OK, so just because her truth-telling record isn’t spotless and she has motives for painting Islam and Muslims in the darkest possible terms, don’t the facts speak for themselves in this case? Yes, and no. My short answer is in three parts:

… she is pointing to a real problem that Muslim leaders need to address more than they have up to now;

… the growing attacks on Christian minorities by Muslims is a much more complicated issue than she makes it out to be;

… the tone and word choice, and Newsweek’s publishing it (on the cover, no less!), are all sensational and likely to fan even more the flames of fear and rancor.

Now for the long answer.

Widen your camera’s scope!

Hirsi Ali is right about one important fact. Christians in many Muslim-majority countries today live in fear. That is a deplorable situation that indeed needs to be discussed at the highest levels – but not in these terms. I’ll come back to her “war” discourse, but let me say here that the causes are multiple and that they vary from setting to setting. Let me add too, for the record, that this is not the case everywhere.

Nigeria’s poisonous brew of postcolonial woes

She starts with Nigeria and all the dastardly attacks by Boko Haram she mentions did take place. This is a home-grown jihadi organization that recently has linked up with al-Qaeda, according to their spokesman, Abu Qaqa, in a recent interview. Indeed, their goal is nothing short of bringing the government to its knees and replacing it with one that follows “the dictates of Allah.” But Nigeria’s tensions between its Muslim north, Christian south, and minorities in either place, have roots in the distant past.

Part of the problem comes from the vast oil reserves that are all located in the southern delta of the Niger River. Compare this to Iraq, where the oil wells are either in the north with the Kurds, or south among the Shia, but none in the Sunni middle. In both countries, oil creates bitter strife and contention.

Another factor is that the dominant tribe to the north, the nomadic Fulanis, who are still spread over several nations, used to be the dominant force in the region, mounting numerous raids to the south to grow their slave population. This was not about religion, but mostly about power and economic interests. Since the south is more developed economically, many families and clans from the Muslim tribes in the north have moved south over time.

In the central city of mwo4m, for instance, where up to last year most of the sectarian violence was located, the violence is reminiscent of the tensions between farmers and cowboys in the classic musical “Oklahoma.” The Christian farmers have resented the northern intruders and have often barred them from voting. Feeling disenfranchised, the Muslims resort to violence and the cycle feeds itself. So far, the number of victims has been fairly even on both sides.

This June I go back to Nigeria for a third two-week intensive course in a large seminary in Lagos. Some of the pastors I teach about Islam, apologetics and peacebuilding are in the north. And I’m sure the stories I’ll hear this year will be worse than ever. If anything, the rapid rise of Boko Haram could not have been possible without tacit support from at least some parts of the population. Clearly, Christian minorities in the north and Muslim minorities in the south tremble at the thought of an all-out civil war. Not surprising, after the recent spate of church bombings since Christmas, the highest profile Christian leader announced that this was a declaration of war and that Christians had the right to defend themselves wherever and whenever they could.

Yet, like the protracted war in Ireland pitting Catholics against Protestants, the Muslim-Christian struggles in Nigeria are less about religion than they are a mix of postcolonial woes and real-life issues of power disparities and injustice in a context where governance has long been characterized by corruption and incompetence. Enter Boko Haram (“Western Education is forbidden”) … This jihadi-salafi ideology (see my blog on this), without a doubt, is pouring oil onto the fire. Still, none of this bears out Hirsi Ali’s allegation of “a global Muslim war on Christians.”

In fact, the maverick mufti from Qatar and the religious rock star of al-Jazeera with a devoted global following of several hundred million, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, has issued a fatwa condemning the violence on both sides and calling on the Nigerian government “to provide security and safety for all people in order to prevent strife among religious groups.” In the same statement he and the International Union of Muslim Scholars, which he heads, denounce the heinous acts of Boco Haram which are responsible for killing 150 people since Christmas 2011, "Muslims, Christians and policemen." Some Muslim leaders are speaking out; and they rightly point out that the victims are both Muslim and Christian.

Sudan’s troubled history

Hirsi Ali then moves on to Sudan. Admittedly, after the 1989 coup by which General Omar al-Bashir took over, the war with the mostly Christian south only intensified. What is more, under the strict Islamist ideology of Hasan al-Turabi, life became nearly intolerable for the Christians in the north. Easily two million people died in this 22-year war; yet skirmishes continue in border regions, despite the 2005 peace treaty and the January 2011 referendum that sealed the south’s independence. Meanwhile, another million or so people died in the brutal attacks in Darfur – once again, nomads against farmers, but all Muslims this time.

So let’s be fair: these are all common symptoms of postcolonial chaos and growing pains, especially in Africa. The mayhem is indicative of a civil war with both parties fighting. Still, responsibility lies mostly with the north – it’s for good reason that al-Bashir stands indicted for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court.

Egypt’s revolution and bumpy road ahead

Are Christians in Egypt and Iraq afraid these days? Yes, they are. But again, reasons differ. Having lived three years in Egypt in the 1990s, I can tell you that Christians have complained of discrimination and harassment from time immemorial. Sadly typical, a recent rampage against Christians in a mostly Muslim village resulted in eight Christian families expelled from the village, by decision of the local authorities. The victims were punished. In a positive development, members of parliament in Cairo stepped in to bring back five of those families. Still, a long history of prejudice and discrimination won’t go away over night.

Add to this the euphoria and chaos unleashed by the January 25 Revolution. For many Egyptian Christians, annoyance gave rise to fear. In the uncertain transition from a dictatorial government to one firmly in the grip of a military junta, which is only reluctantly ceding power to an elected parliament – whose overwhelming majority is one brand of islamism or another – any minority is going to feel vulnerable. Add to that attacks on churches with dozens killed, and even the tragic incident of the army deliberately killing peaceful Christian protesters in early October (for a larger context, see my blog on this). I never read Hirsi Ali’s figure of 200,000 Copts fleeing their homes, but I’m sure more Egyptian Christians than before are trying to emigrate.

Nevertheless, many Egyptian Christian leaders remain optimistic, figuring that while the road to democracy is bound to be treacherous, it will open up better opportunities in the long run. They have ruled out the idea of a “Christian” political party, banking on more fruitful alliances with the dominant Justice and Freedom party and its coalition partners – that do not include the ultraconservative Salafi Nour party.

Iraq, a wounded nation “pacified” by force

Iraqi Christians, by contrast, are not so upbeat. Hirsi Ali correctly notes that half of the mostly Assyrian Christians of Iraq have fled the country since the US invasion of 2003. What she leaves out of her “story telling” is that this is mostly due to the American military occupation and the violence it has spawned in Iraq. Though Sunni-Shii tensions are longstanding, Muslim-Christian ones, unlike Egypt, are not. Christians since 2003 have been perceived as somehow collaborators and thus scapegoats for the violence perpetrated by a “Christian” nation on them. Apparently, you can’t impose democracy on a nation by force – and especially one where ethnic and sectarian tensions run deep, ever embittered by the uneven distribution of oil wealth.

Pakistan and Afghanistan: a cauldron of acrimony and violence

Hirsi Ali mentions a growing number of attacks against Christians in Indonesia, and again, a lot more could be said about ethnic tensions, political grievances, and the like. She rightly calls Saudi Arabia’s handling of religious minorities “totalitarian restrictions.” But I would like to comment on Pakistan, which I see as perhaps her strongest case. Indeed, since at least the 1980s, there has been a hardening of Islamic traditional norms, and the military, in its bid to control the political elites, has only made the political opposition harden its islamist rhetoric.

Yet by far the biggest factor for Islamic radicalization in Pakistan has been the war in Afghanistan. Its government turned to Islamic symbols to counter foreign imperialism, first in supporting the CIA-backed mujahiddeen against the Soviets in the 1980s, then in their alliance with the Pashtun-led Taliban state in the 1990s. Hence, the genie was let out of the bottle, so that with the Nato-led coalition invasion of 2001, years of bitter fighting, scores of civilian casualties, and now following regular drone attacks on Pakistani soil, anti-American resentment has reached a boiling point in Pakistan. This kind of resentment only produces more venom against the already beleaguered Christian minority (about 1%).

Having said that, some clear-cut human rights violations are practically written in the law of the land. When religious positions harden in Muslim contexts, minorities suffer. The medieval law of apostasy, still on the books in a religious sense, comes into force and its corollary, the law of apostasy is, as Hirsi Ali writes, “routinely used by criminals and intolerant Pakistani Muslims to bully religious minorities.” And yes, two high profile politicians, including Punjab’s former governor Salman Taseer and the most influential Christian lawmaker, the Minister of Minority Affairs Shahbaz Bhatti, were both gunned down in January and March of 2011. Both had campaigned for the repeal of the blasphemy laws (for more on apostasy, see my blog).

Hirsi Ali mentions the attack on the World Vision compound in 2010, in which six people were killed and four wounded, and connects this to the blasphemy laws that make confessing one’s belief in the Trinity a crime. Indeed, this was a brazen act, and considering World Vision is extremely careful to avoid any action that even looks like proselytism, one can only conclude that even the presence of foreign Christians is intolerable to some Muslims.

What about Afghanistan? Carl Moeller, president of Open Doors USA, one of several evangelical organizations that specialize in helping persecuted Christians around the world recently wrote a piece entitled, “Will There Be a Place for Christians in Muslim-Majority ‘Arab Spring’ Countries?” Though I don’t necessarily agree with all that he writes (I would be more upbeat about Egypt, Lybia and Tunisia, for instance), I stand by his analysis of the situation in Afghanistan – though I have to wonder why it’s included (it’s obviously not an Arab country!). In 2010, the last standing church structure was bulldozed and the traditional apostasy law is routinely enforced. Afghans by law must be Muslim. He mentions a recent State Department report informing us that “Afghanistan’s media law prohibits publicizing and promoting religions other than Islam.”

Every year the Open Doors World Watch List ranks the fifty countries where Christians are most persecuted. In the 2012 version, 39 were Muslim-majority countries. North Korea has been at the top of the list for decades, but Afghanistan moved up to second place, just ahead of Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Iran and the Maldives. Pakistan was listed at number ten.

Hirsi Ali’s “War on Christians” Discourse

By now you are probably saying, “isn’t this exactly what Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote in ‘The War on Christians’”? As I answered in the beginning, “yes and no.” Many of the facts are correct, but the context is missing. With a wider angle camera focused on each of the countries mentioned here, I hope that it’s clear that there is no “war” declared by Muslims against Christians on a global scale. Hirsi Ali herself tries to downplay the title of her piece at one point. She writes,

“No, the violence isn’t centrally planned or coordinated by some international Islamist agency. In that sense the global war on Christians isn’t a traditional war at all. It is, rather, a spontaneous expression of anti-Christian animus by Muslims that transcends cultures, regions, and ethnicities.”

OK, it’s not really a “war” against Christians. So don’t say it. And don’t put it in the title. Maybe it was Newsweek that, anxious like any media outlet to boost its sales, insisted on the title. Certainly the bloodied icon on the cover was meant to add to the sensationalism and elicit emotion – should I say shock and outrage?

There is another motive in Hirsi Ali’s piece. See for yourself:

“Over the past decade, these [the OIC and CAIR] and similar groups have been remarkably successful in persuading leading public figures and journalists in the West to think of each and every example of perceived anti-Muslim discrimination as an expression of a systematic and sinister derangement called ‘Islamophobia’—a term that is meant to elicit the same moral disapproval as xenophobia or homophobia.”

So this is it: she’s setting out to counter what she perceives as a smear campaign on the part of some Muslim organizations – a campaign that has been remarkably successful. Hence, she fights back. Her objective in this article is to pit the annoying but rather “minor” discrimination that Muslims face in the West against the outright persecution and killing of hundreds of Christians every year in Muslim countries.

To make this contrast really work, she coins an equivalent word, even though she has deridingly characterized Islamophobia “as an expression of a systematic and sinister derangement … meant to elicit the same moral disapproval as xenophobia or homophobia.” Never mind, “Christophobia” will do just fine.

This is political wrangling, and it is much more than just sparring about words. In the academic disciplines of the human sciences (from literary criticism to philosophy, history, sociology and anthropology) we call this mounting an oppositional “discourse.” More than simply language, creating a discourse is to construct a series of arguments from a particular perspective (we all have one – total objectivity is impossible). But it’s more than just words and arguments. Tone is crucial too.

On the one hand, Hirsi Ali’s piece is considerably toned down, compared to writings by Robert Spencer, Brigitte Gabrielle, or Daniel Pipes. On the other hand, she deftly builds her case by piling the most egregious acts against Christians one on top of the other and then saying, “[i]t should be clear from this catalog of atrocities that anti-Christian violence is a major and underreported problem.” This, combined with a contemptuous dismissal of Muslims’ complaints about “Islamophobia,” allows her to build up to her conclusion:

“Instead of falling for overblown tales of Western Islamophobia, let’s take a real stand against the Christophobia infecting the Muslim world. Tolerance is for everyone—except the intolerant.”

Here “Christophobia” is a virulent infectious disease that must be denounced. And then the eminently reasonable word – a darling of liberals, but which conservatives cannot dismiss either – “tolerance.” Contrast her tone to that of a recent Economist article on the same topic, or, better yet, the masterful work of scholar, clergyman and longtime resident in Lebanon and Egypt, Colin Chapman ("Christians in the Middle East: Past, Present and Future").

Notice too the use of “tale”: for her, “tales of Islamophobia” are all about exaggerated storytelling to make people sorry for Muslims. But the shoe fits on her foot too: her article is about telling a tale of woes suffered by Christians in Muslim lands. Is the litany of suffering on the Christophobia side of the ledger so many times worse than that on the Islamophobia side? Yes, in the sense that many basic human rights are denied to non-Muslims in Muslim-majority contexts and that there is much loss of life. No, in the sense that the suffering is caused by many more factors than intentional persecution. Other minorities are oppressed too. Besides, Muslims suffer as well from the lack of freedom of expression and conscience. In fact, if you count numbers of casualties, Muslims are by far the greatest victims of extremist violence.

To sum up, Christians do suffer in some Muslim countries. Some of it is outright persecution. Yet most of this hardship is due to a brutal convergence of factors that affect many Muslim societies as a whole: authoritarian regimes (thanks to the “Arab Spring,” that is beginning to change); economic woes made worse by corrupt governance; a groundswell of puritanical and intolerant religiosity; and an angry reaction to western military and political interference.

Hirsi Ali’s tale of Christophobia told in this way is inflammatory. While raising an issue that deserves careful consideration on a global scale, the tone and tenor of her article will likely short-circuit needed negotiations.

[A slightly different version of this blog was posted on the Peace Catalysts site in Nov. 2011]

Haroon Moghul is the epitome of the young, charismatic and connected American Muslim leader. A PhD candidate at Columbia University, he is a sought-after speaker on the interfaith circuit (including CNN, NPR, the New Yorker and the Guardian). He’s also a popular blogger and a regular contributor to the Huffington Post and Religion Dispatches. A web bio says he lives with his wife in New York City.

Moghul’s latest piece in Religion Dispatches describes his experience as an “undercover” Muslim attending an all-night Christian prayer vigil at Detroit’s Ford Field stadium. But these weren’t just any Christians. This was a TheCall event led by New Apostolic Reformation leader Lou Engle – the man who helped launch Governor’s Rick Perry’s presidential campaign at a Christian prayer rally last August.

A rally to send prayers over the Michigan mosques “like sending special forces into Afghanistan” doesn’t just send shivers down the backs of Muslims like Moghul; it gives Christians like me the jitters. But aren't you an "evangelical" too, you might be asking?

Quick parenthesis: I don't like labels, but I’ll accept the “evangelical” one, so long as you identify me with my friends at Peace Catalysts, and with a large wing of the movement that cares deeply about living out the love, respect and compassion Jesus showed toward the poor and despised of his day. Yes, I strongly believe his cross and resurrection are the lynchpin of human history; and that’s precisely why I’m so passionate about peacemaking, social justice, preserving the planet, and interfaith dialog.

I think Jim Wallis and Sojourners magazine nicely represent the growing number of evangelicals like myself who give the lie to those on the Religious Right and the secular Left who “describe evangelicals as zealous members of the ultra-conservative political base” (see his editorial in Sojourners, February 2012, or the Huffington Post article). Pigeonholing religious people – of any faith tradition – is risky business.

Meanwhile, back in Detroit, local clergy got wind of the upcoming TheCall rally. They were so upset that they set up an alternative rally of their own at the same time (see Detroit Free Press article). To Engle’s assertion that TheCall was “about turning America back to God” these Detroit church leaders retorted that he was preaching “a radical ideology that promotes hatred of gays, Mormons, Oprah Winfrey, Catholics and, increasingly, Muslims.”

The Rev. Oscar King, senior pastor of Northwest Unity Baptist Church in Detroit, also objected to TheCall’s patronizing attitude: “They're acting like we're some Third World, underdeveloped country and they're going to bring us Jesus.” Add to that a militaristic ethos that blends the spiritual with actual US foreign policy: “Leaders of the rally are calling upon Christians to target mosques across metro Detroit, comparing their efforts to the Crusades, D-Day and U.S. wars in the Muslim world.”

Actually, Haroon Moghul’s experience during the first five hours of the rally was mildly positive. First of all, no derogatory references to Muslims and no mention of gays at all. Sitting near the front, like everyone else he was swaying and dancing to the Jesus rock music, “perfectly blending in” (and likely scared not to!). Then too, he was awed by the diversity of attendants – this part “seemed to be a public relations dream come true.”

Still there was a gnawing sense that the kaleidoscope of colors and ethnicities was simply like the “united colors of Benetton” – a marketing ploy by multinationals to sell their merchandise and plug the neoliberal system that allowed them to better plunder poorer countries in the process. Or a political campaign with faces of color, “even while social mobility goes into steep decline and the middle class is eviscerated.”

I’ll come back to the political message, but at this point Moghul drops a fascinating comment. He’s uncomfortable with the music and the “worship” it represents, mostly because it’s coming from a faith tradition very foreign to him. He explains that for him as a Sunni Muslim (hinting that he has some Sufi sympathies as well) “worship” is about “the effort to establish an immediate, intimate, and contemplative connection with God”; it’s about a spirituality based on a religious law that lays out specific rituals and provides guidance in daily life.

Moghul couldn’t help it – he felt like an outsider, “because, after all, religions are not interchangeable, like different color cars of the same make and model.” Yet that was not what he found objectionable about the gathering. It was normal: he was not a Christian, and therefore could not resonate with the ambient spirituality.

Around 11 p.m., Moghul decided to take a break. He retired to an Arab restaurant, ate a meal served by a waitress in hijab, and then caught a couple of hours of sleep. Refreshed, he returned to the stadium for the 3 to 6am culmination of the vigil focusing on Muslims. This is when Moghul did start to object.

Entitled “Dearborn Awakening,” this section of the program offered prayers against the rising Islamic movement in America, of which Dearborn was its “Ground Zero.” This conspiracy discourse was taken straight from the popular speaker, US Army Lt. Gen. William Boykin, who regularly asserts that “Islam is a totalitarian way of life” and that “it should not be protected under the first amendment”; furthermore, that there should be “no mosques in America,” since “there is no greater threat to America than Islam.”. TheCall’s own rhetoric was all about “taking back the land” occupied by Islam in this country. That was troubling enough, writes Moghul, but the worst was yet to come.

That was when a former Muslim, “Kamal,” stood up to speak. Several aspects of this man’s story coalesced to convince Moghul that Kamal was a fraud: his ex-terrorist Lebanese background, his military missions at age 8, the erroneous claim that martyrs become “messiahs,” or that violent jihad is the only way to salvation. Maybe he wasn’t a fraud, muses Moghul, trying to give him the benefit of the doubt. But then all his talk about Muslims worshiping an idol, a false god, in total contrast to the loving and compassionate God of the Bible – this was an outright lie, a complete misunderstanding of the teaching of Islam.

So Moghul’s biggest problem with TheCall was about the outright lying and distortion of Islam. Here’s the heart of his article, the one great takeaway from his undercover experience that night:

“All the friendly diversity from Friday night, the warm and smiley openness, had vanished. Love and freedom were convenient catchphrases justifying the identification of nearly one-quarter of humanity with the demonic. It’s one thing to say that you’d like Muslims to convert to Christianity. Fair enough. Many Muslims want Christians to convert to Islam. It’s another thing to so brazenly misrepresent Islam. Conflicts in the past could be safely broached, but when it came to today’s war on terror, the disingenuousness and ill-spiritedness of choosing a former Muslim with the worst possible perspective on Islam revealed Engle’s agenda and its overlap with fearmongering Islamophobes.”

Here’s my own takeaway, in the spirit of Peace Catalysts’ stated values.

1. Above all, we seek to represent Muslims honestly, with credible research; but too, we do this with a bias toward love and peacemaking.

2. Moghul had no problems with Muslims and Christians wanting to share their faith – both sides just need to do outreach with respect and a heart that is open to listen to and learn from the “other.”

3. Let’s be up front about our politics. Moghul nailed it: Engle is closely allied with the current Republican caucus. He seems to be allergic to the idea of any state trying to provide a modicum of social justice. Unfortunately, this tends to go hand in hand with an aggressive foreign policy that seeks to uphold global US hegemony, militarily and otherwise. Politics do count, but neither should we be partisans. So as much as possible, let’s stick to principles and values that transcend current political divides – like the Bible and the Qur’an’s bias toward the poor and the inherent dignity of every human being, regardless of race, ethnicity, class, or religion.

4. As a Christian, I weep over the deceit (whether intended or not) of having great worship music and inspirational messages about the rainbow nature of the church worldwide coupled with an attempt to shove under the radar a program aimed at demonizing a billion and a half Muslims. That is so sad!

5. Our best retort, however, is not to demonize TheCall in return, but to multiply successful initiatives and cooperative ventures between Christians and Muslims that really do make a difference in the world, all in remaining true to our Lord Jesus.

To close, I want to thank Haroon Moghul for going to TheCall in Detroit and for writing this honest piece on his experience. I’m trying to follow Christ with all my heart, mind and strength. This piece forces me to be honest about the degree of integrity with which I do that.

[This is the 4th and last installment of the series, “Earth Warming, Faith Rising?”]

If you go back to the trailer of the “Renewal” documentary mentioned at the end of the last blog, you will hear the voice of a doctor saying that strip-mining is the equivalent of raping the land – “it’s obscene, it’s a sin.” Then he adds, “Evangelicals are starting to recognize that environmental stewardship is a deeply moral and biblical issue.”

I will get back to the issue of Evangelicals and ecology in the last part of this piece. But this is an apt summary of the themes I’ll deal with here – caring for the earth is a profoundly moral issue. And, let me add, there is a lot more to it than just global warming.

Just as Muslims hail from very diverse cultures, theological positions and spiritual orientations, so in the same way Christians occupy many different points along a wide spectrum. In this blog I’ll pick the three most influential movements in the United States and pin point some who are truly “investing in our planet,” that is, who are taking concrete steps to curb greenhouse gas emissions, to rein in different kinds of pollution that disproportionately injure the poor, and to find creative ways of bringing people into harmony with God’s good creation.

First we look at a fascinating interfaith initiative by an Episcopal priest and delightfully charismatic woman, Rev. Canon Sally Grover Bingham. Then we’ll move on to the Roman Catholic Church, then on the seismic shifts in the Evangelical community.

The Interfaith Power and Light (IPL) is a formidable machine of sociopolitical change. Already with 38 state affiliates, IPL is now helping over 14,000 US congregations across the religious landscape shrink the carbon footprint of their institutions and homes. Alongside this ecological advocacy and training, the IPL aims to leverage the passion of religious people …

1. to spark a wider movement for environmental awareness

2. to lobby for “public policies in the political arena to advance clean energy and to limit carbon pollution”

The first paragraph of its mission statement reads:

“The mission of Interfaith Power & Light is to be faithful stewards of Creation by responding to global warming through the promotion of energy conservation, energy efficiency, and renewable energy. This campaign intends to protect the earth’s ecosystems, safeguard the health of all Creation, and ensure sufficient, sustainable energy for all.”

The IPL was launched in San Francisco at the Grace Cathedral in 1998 and quickly developed as a coalition of California Episcopal churches. Then in 2000 it widened its appeal to congregations of all faith traditions, sparking a movement that “helped pass California’s landmark climate and clean energy laws.” To date, California has the most stringent vehicle fuel efficiency standards. In January 2012 the state set the goal of halving greenhouse gas emissions and growing a fleet of 1.4 million zero emission vehicles by 2025 ( see businessgreen.com). IPL is likely the most influential faith-based NGO behind these tougher standard.

Much of the credit for these successes goes to Sally Bingham, the founder and president of the Regeneration Project, which spun off the IDL campaign. Due to her stellar achievements in the environmental field, she has received numerous honors, including three honorary doctorates. According to her bio, she was “named one of the top fifteen green religious leaders by Grist magazine, was written up in O Magazine, and has been recognized as a Climate Hero by Yes! Magazine.” She sits on the boards of the Environmental Defense Fund and the Union of Concerned Scientists. Finally, she gathered twenty other religious leaders to write a book with her in 2009, Love God, Heal Earth.

You might be asking, “how Christian is this project?” It’s Christian in the sense that the founder is a member of the clergy and that faith was the inspiration behind her own tireless efforts over the last couple of decades. But IPL is also by design an interfaith project – securing the participation of the widest possible spectrum of religious communities. Environmental issues have been high on the agenda of Mainline Protestant churches for decades now, with the US Roman Catholic Church not far behind. Sally Bingham’s genius was to cast the net much more widely, seeking to spur those who hadn’t either given the ecological crisis much thought, or hadn’t done much about it yet. The IPL mission statement addresses this priority:

“Global warming is one of the biggest threats facing humanity today. The very existence of life — life that religious people are called to protect — is jeopardized by our continued dependency on fossil fuels for energy. Every major religion has a mandate to care for Creation. We were given natural resources to sustain us, but we were also given the responsibility to act as good stewards and preserve life for future generations.”

Since the 1970s a lay Catholic movement had been slowly gathering momentum in a quest to bring “an environmental ethic of stewardship” to the attention of church leaders. Then Pope John Paul II made this declaration in a 1990 message on the occasion of the World Day for Peace,

“The gradual depletion of the ozone layer and the related ‘greenhouse effect’ has now reached crisis proportions. . . . Today the ecological crisis has assumed such proportions as to be the responsibility of everyone…. When the ecological crisis is set within the broader context of the search for peace within society, we can understand better the importance of giving attention to what the earth and its atmosphere are telling us: namely, that there is an order in the universe which must be respected, and that the human person, endowed with the capability of choosing freely, has a grave responsibility to preserve this order for the well-being of future generations. I wish to repeat that the ecological crisis is a moral issue.”

This message (“Peace with God the Creator, Peace with All of Creation”) was a great boon to all the activists struggling in the shadows. It became the necessary launching pad for a reinvigorated campaign of environmental awareness and commitment in the wider Catholic communion. Then in 1993 the US Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) issued a declaration, “Renewing the Earth: An Invitation to Reflection and Action on Environment in Light of Catholic Social Teaching.” The following year, with help from the National Religious Partnership for the Environment, the USCCB established the Environmental Justice Program formed around the same time.

Meanwhile, small grants were given to those congregations and dioceses willing to implement projects on behalf of the poor threatened by environmental hazards, to reclaim dilapidated properties for green purposes, and to “advance new regulations on mercury emitted from coal-fired power plants” (catholicclimatecovenant.org).

Notice the unique contribution of Catholic social ethics to this wider faith-based coalition. The longstanding principle of the “preferential option for the poor” is clearly woven into this Catholic concern for those most devastated by the impact of industrial pollution and climate change. Hence the USCCB issued another pastoral letter in 2001, entitled, “Global Climate Change: A Plea for Dialogue, Prudence and the Common Good.” This led in 2006 to the launching of the Catholic Coalition for Climate Change, bringing under its wing a dozen national Catholic organizations desiring to integrate ecological justice into their existing programs. As one might expect, this activist network was able to implement significant change at the parish and diocesan levels too.

Then on World Peace Day, exactly twenty years after John Paul II’s landmark address on faith and environment, Pope Benedict XVI chose to build directly on his predecessor’s legacy. Take note especially of the link he draws between creation care, social justice and peace:

“If You Want to Cultivate Peace, Protect Creation…. Man’s inhumanity to man has given rise to numerous threats to peace…. Yet no less troubling are the threats arising from the neglect – if not downright misuse – of the earth and the natural goods that God has given us…. Can we remain indifferent before the problems associated with such realities as climate change … attention also needs to be paid to the world-wide problem of water and to the global water cycle system, which is of prime importance for life on earth and whose stability could be seriously jeopardized by climate change.”

[For more details on this section, see my paper “Evangelicals and Ecology”]

Evangelicals, by definition, have no centralized institutions like their Catholic brethren. The closest you come to the USCCB is the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), which claims to speak for 45,000 congregations scattered across some forty conservative Protestant denominations. The watershed document on sociopolitical involvement for this group came in 2004, “For the Health of the Nation: An Evangelical Call to Civic Responsibility."

Three brief historical remarks will help you see why I use the word “watershed”:

1. Heirs of the “fundamentalist” movement of the 1920s (think of the “Scopes Trials”), evangelicals broke off from their inward-looking, bunker-mentality conservative Protestant brethren after WWII, mostly under the leadership of Billy Graham and Harold John Ockenga and under the banner of institutions like Fuller Theological Seminary. The newer label “evangelical” in this context implied more self-confidence about one’s faith and one’s ability to both evangelize and engage the wider culture intellectually.

2. A 2000 book by sociologist Christian Smith (Christian America: What Evangelicals Really Want) provided some useful data about US conservative Protestants (29% of the total population). Smith discovered that the best way to understand this population was to use the respondents’ self-identification in his survey work. This resulted in three overlapping groups: “evangelicals” (11.2 percent); “fundamentalists” (12.8 percent); and “members of conservative Protestant denominations.”

2. The birth of the Christian Right in 1979, sparked by the parallel efforts of Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, marked the beginning of an evangelical/fundamentalist bid for political power. Yet with prominent organizations like Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council at the forefront, it was almost exclusively focused on overturning the Roe vs Wade ruling on abortion, reestablishing (Christian) prayers in public schools, and reversing the advance of gay and lesbian rights.

All along a minority view had been pushing for a wider evangelical agenda – in the words of the Sojourners’s website, an agenda of “racial and social justice,” “life and peace,” and “environmental stewardship.” Both Jim Wallis of Sojourners and Ron Sider of Evangelicals for Social Action began their parallel movements in the early 1970s.

With all this as a backdrop, it does seem that the 2004 NAE document For the Health of the Nation was pivotal. Yet, for all its advocacy of Christian involvement in bettering all aspects of American society, it was nearly silent on environmental issues:

“Evangelicals may not always agree about policy, but we realize that we have many callings and commitments in common: commitments to the protection and well-being of families and children, of the poor, the sick, the disabled, and the unborn, of the persecuted and oppressed, and of the rest of the created order. While these issues do not exhaust the concerns of good government, they provide the platform for evangelicals to engage in common action.”

Only the phrase “the rest of the created order” hinted at some ecological awareness. Clearly, some powerful leaders in the movement opposed any language that might refer to global warming. While the “Christian Right” and the wider Republican establishment still officially repudiate the notion that climate change is either happening, or – Heaven forbid – might be caused by human behavior, a growing number of Evangelicals (and especially in the twenty-somethings bracket) are certain that environmental destruction is an urgent problem right now.

Behind the scenes – also going back to the 1970s – was the work of Calvin DeWitt, environmental scientist and founder of the Evangelical Environmental Network (EEN), who in 2002 organized a church leaders conference in Oxford, UK, for the purpose of learning about the dangers of global warming by a panel of climate scientists. Four years later, this movement produced a landmark declaration, the Evangelical Climate Initiative. You can read its official statement, “Climate Change: An Evangelical Call to Action.”

Of course, contrarians too have invested a lot of money and effort to refute what they consider a distortion of science by liberals – indeed, more than a religious question, this is about politics. For an example, see the Cornwall Alliance declaration.

At the end of these four blogs on faith and ecology, which I’ve called “Earth Warming, Faith Rising?”, some words of caution are in order. Despite the heartening momentum evident in all three circles considered in this piece (Mainline Protestants, Roman Catholics, and Evangelicals), there is still much apathy when it comes to “going green” in people’s personal lives and in the institutional ways of the church. As I see it, Rev. Sally Bingham’s grassroots, interfaith approach holds the most promise for actually educating us and getting us to shrink our carbon footprints (I confess my own foot-dragging in this area!). Also, I would add the Catholic emphasis on standing up for those most affected by pollution – it’s the poor and most often people of color who are the greatest victims of toxic landfills and industrial pollution. Sadly, Evangelicals at the moment are too divided to effect real change in the wider culture.

Some readers might have gathered from the last blog that Muslims worldwide are massively involved in environmental activism. That is not the case. Apart from the wrangling that has taken place in the halls of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, where political leaders barter back and forth and argue about who is going to dole out aid to the poorest countries most devastated by climate change; and apart from Indonesia where religious leaders have begun a grassroots campaign to curtail the abuses of big-business logging, mining and oil production – most Muslim countries have had to set economic development as their top priority (see Richard Foltz’ great article on “The Globalization of Muslim Environmentalism." Nevertheless, as I tried to show, there is definitely a movement afoot to put a sustainable environment on the agenda of Muslims worldwide.

Indeed, the earth is warming, and the faith of Muslims and Christians – whose teachings overlap so dramatically on God’s call for us to care for creation – is rising to meet this challenge, however slowly. Whatever our own faith or non-faith background, let each one of us do his or her part to protect and to share equitably the bountiful resources God’s earth holds for all of us. It is, after all, a “deeply moral issue” – a biblical and qur’anic imperative.

This piece was cut out of a chapter that was contributed to the volume coming out this year, Fundamentalism: Perspectives on a Contested History (co-edited by Simon A. Wood and David Herrington Watt, University of South Carolina Press). It was going to compare Muslim and Evangelical involvement in environmentalism, but in the end the editors took out the Christian side. Here it is. Its title is "Fundamentalism Diluted: From Enclave to Globalism in Muslim Ecological Discourse." Refer back to the blog series on fundamentalism to get the context of this short piece.

[This is the 3rd installment of the series, “Earth Warming, Faith Rising?”]

“Investing” is a business term. People invest in start-up ventures that seem promising; in company stocks that are slated to rise; in a property whose market value is climbing. In each case, the investor expects to reap financial dividends.

People invest in charities too. They invest their time and skills as volunteers to tutor underprivileged children after school, or to help run a food bank. Those dividends are not financial, but still just as tangible. We do this with great satisfaction, because we are helping others develop their potential, or we’re simply alleviating human need.

I have no doubt that “investing in the planet” will reap great dividends, though many will only be counted down the road. Investing in clean energy, for instance, will decrease greenhouse gas emissions, thus slowing down global warming. Then less temperature increase will reduce the number and intensity of future weather disasters and curb the rise of sea levels – all of which disproportionately affects the poor.

That’s for climate change mitigation. Let’s add two more factors: investing in the planet also means removing all the socioeconomic and political barriers that keep the poor beaten down (social justice) and reducing conflicts and wars that create such havoc around the world (peace building).

Now you have the three core principles behind the Earth Charter. What is the “Earth Charter,” you ask?

Initiated by the United Nations around 1990, the Earth Charter Commission was run by a coalition of NGOs and activists from around the world. After much networking by email, phone conversations and conferences, the final product was rolled out in 2000. Here is the preamble:

“We stand at a critical moment in Earth's history, a time when humanity must choose its future. As the world becomes increasingly interdependent and fragile, the future at once holds great peril and great promise. To move forward we must recognize that in the midst of a magnificent diversity of cultures and life forms we are one human family and one Earth community with a common destiny. We must join together to bring forth a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace. Towards this end, it is imperative that we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations.”

This document was in part behind the paper I presented (see a more recent blog on this) at the American Academy of Religion in its 2010 annual meeting in Atlanta. What is striking in its wording is the emphasis on the interconnectedness of all humans sharing one planet, and their close ties to “the greater community of life” – another way of saying “nature,” “creation” (from a monotheistic perspective), which includes animate and inanimate beings.

This blog looks at the idea from a Muslim viewpoint and the next one does the same for Christians. I will start with the theological tenets that crop up most often as Muslims today write about the environment. That will lead into naming some of the key players in today’s “greening of Islam.”

Tawhid, Khilafa, conservation, and care for all creatures

Tawhid (literally, “the process of making things one”) first designates the unity of God. Islam is fiercely monotheistic, as is Judaism. Christians too believe in only one God, but the Bible adds that he was fully embodied in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, who preached and demonstrated the kingdom of God through the power of the Holy Spirit. One of the earliest suras of the Qur’an directly pushes back against this idea, because it interprets it literally (“sonship” is clearly figurative in the New Testament):

“Say: He is God, the One and Only God,

The Eternal, Absolute

He begetteth not, nor is He begotten

And there is none like unto Him” (Q. 112)

From the absolute oneness of God, then, flows the oneness of all creation, since every part directly connects to him, by virtue of its origin and by virtue of his constant, sustaining power. Islam means “surrender” or “submission” to God. Every organism, rock, tree, ocean and planet submits to the laws he puts in place. In that sense they are all “muslim.” From the start only humankind, once fashioned by God, received the breath of God’s Spirit:

“Behold, thy Lord said to the angels: ‘I am about to create man from clay: when I have fashioned him (in due proportion) and breathed into him of my Spirit, fall ye down in obeisance unto him.’” (38:71-2)

The angels were commanded to bow down to Adam for another reason too, as we read in Sura 2 (“The Cow”). Here the angels, upon hearing that God was about to place Adam on earth as his “caliph” (khalifa, meaning trustee, deputy, representative), were stunned. God gave them proof that this creature was totally unlike all other creatures. He is taught “the names of all things,” meaning that humanity alone is endowed with reason (i.e., with the power to create science and technology) and conscience (he alone can choose to submit to God or not). So we read,

30. Behold, thy Lord said to the angels: “I will create a vicegerent on earth” They said: “Wilt Thou place therein one who will make mischief therein and shed blood? Whilst we do celebrate Thy praises and glorify Thy holy (name)?” He said: “I know what ye know not.”

31. And He taught Adam the nature of all things; then He placed them before the angels, and said: “Tell me the nature of these if ye are right.”

32. They said: “Glory to Thee: of knowledge we have none, save what Thou hast taught us: in truth it is Thou who art perfect in knowledge and wisdom.”

33. He said: “O Adam! tell them their natures.” When he had told them, God said: “Did I not tell you that I know the secrets of heaven and earth, and I know what ye reveal and what ye conceal?”

34. And behold, We said to the angels: “Bow down to Adam:” and they bowed down: not so Iblis: he refused and was haughty: he was of those who reject Faith.

This of course is the central theme of my book, Earth, Empire and Sacred Text. The idea that God empowered the children of Adam and Eve as his trustees on earth is the bedrock of Muslim-Christian common ground. This concept first came to me while reading the works of Anglican bishop, Kenneth Cragg, arguably the most astute (certainly the most prolific!) non-Muslim interpreter of the Qur’an. For him, the Qur’an unmistakably links the gifts of reason and conscience to the calling of earth tenancy – “wisely colonizing” the earth (Q. 11:61), as he puts it. So accountable management of the earth’s resources is in itself an act of worship; and this calling to master the earth nicely parallels the earth itself being full of “God’s signs,” as the Qur’an repeats over and over. Borrowing a Christian word, he calls it the “sacramental earth.” In Cragg’s own words,