-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

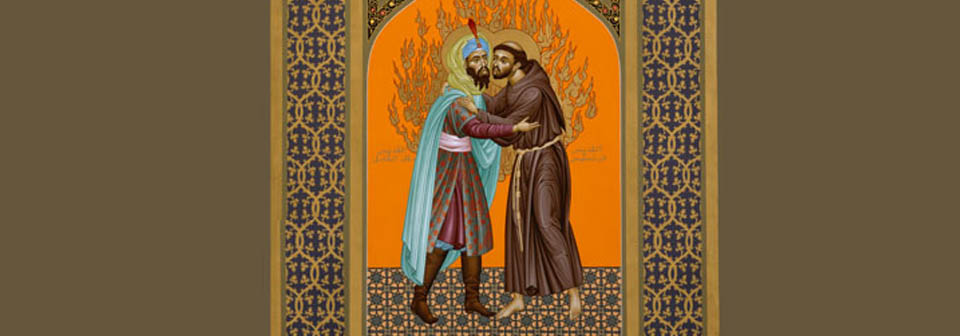

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

My purpose here is simple – to get you to listen to the 54-minute Middle East Eye interview with Oxford historian Avi Shlaim. The first part concerns Shlaim’s biography and the second, as the title suggests, captures his view as an Israeli historian of the current protests and the future of the Israeli state.

How did a Jewish boy born in 1945 to wealthy parents in Baghdad, Iraq, end up in Israel six years later? More intriguingly, how did a young Mizrahi (Arab Jew) who struggled to learn Hebrew and spent four years in a British “public school” (actually meaning “private”), come back for military service in the IDF (1964-66) and become a convinced Israeli nationalist? Perhaps that is understandable. In the interview he explains how military training became a very effective nationalist indoctrination tool. Also, by that age his Hebrew was fluent and he was better assimilated. But what is most stunning in Shlaim’s biography is that barely two years after his return to Britain for his university studies, he was seriously beginning to question the moral foundation of Israel’s policies regarding the Palestinians within its territories. “These are colonial policies,” you will hear him say.

Here are a few points I want to highlight. Hopefully this post will motivate you to actually listen to the whole interview and fill in the blanks, while getting to know this brilliant British academic (he has dual nationality) who in 2006 was elected Fellow of the British Academy.

Iraq a model of Jewish integration for 1,200 years

When a coalition of discontents overthrew the first Islamic dynasty (Umayyads) centered in Damascus around 750, they founded a new dynasty, the Abbasids, which moved to Baghdad. There in the next century, the fifth caliph, Harun al-Rashid, founded a library and center of learning called Bayt al-Hikma (“House of Wisdom”) in which Christian and Jewish scholars were prominent. After all, they had been working for centuries on Greek manuscripts and could readily initiate their Muslim colleagues into the study of thousands of volumes on philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and more. Baghdad became under him a capital of the arts and sciences, a cosmopolitan center of culture, knowledge and trade. By the tenth century, two Jewish schools competed against each other and Jews could be found at all levels of society, including political administration. This remained the same into the 20th century, as Avi Shlaim explains.

With the hardening of Arab nationalist ideology in the 1930s and 1940s and finally, the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, the Jews were suddenly persona non grata. Most of them were forced to leave in 1951 – 120,000 Arab Jews from Iraq joined another 140,000 other Arab Jews from other Arab nations to find refuge in Israel. In reality, they were more tolerated than welcomed in their new home. More on that below.

These Iraqi Mizrahis, or Arab Jews, trace their lineage back to the 6th century BCE when the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and forced many Jews into exile. This is when the prophet Jeremiah, one of the few Israelites staying behind, sent a letter to the exiles in Babylon (just miles from today’s Baghdad): “Build homes, and plan to stay. Plant gardens, and eat the food they produce. Marry and have children. Then find spouses for them and so that you may have many grandchildren. Multiply! Do not dwindle away! And work for the peace and prosperity of the city where I sent you into exile. Pray for it, for its welfare will determine your welfare” (Jeremiah 29:5-7 NLT). Well, they stayed until 1951.

Shlaim talks a great deal about identity. As an Arab Jew, he shared the language and culture of his fellow Iraqis, whether Muslims or Christians. But this only made it more difficult to adapt to a country that had just been founded by European Jews (Ashkenazi).

The shocking role played by Israeli agents in Iraq

Shlaim recounts that, after the founding of Israel, the government of Iraq (similarly in Egypt, Syria, and elsewhere) was looking for a convenient scapegoat for its defeat on the battlefield – a defeat that could only be attributed to its own failed policies. The Iraqi Jews were that perfect scapegoat and “the government pursued official policies of discrimination: Jews were fired from the government service. Restrictions were placed on the activities of the Jewish traders and Jewish bankers, and a quota was imposed on the number of Jews who could go to university.” He sees this as “the main reason for the exodus of the Jews from Iraq.”

But there is another reason as well. Five bombs went off in Jewish spaces between 1950 and 1951. In March 1950, the Iraqi government passed a law that Jewish citizens who wished to leave the country were free to do so. They had one year to register. The response was tepid, so violence was used to speed up their departure. Five bombs exploded in Jewish public spaces during that time, creating a climate of fear and uncertainty for Jews and motivating many more of them to leave. But not all of those bombs were planted by Iraqi Arabs. Shlaim had grown up aware of persistent rumors in the Mizrahi community that Israel itself had been involved in uprooting them from their land, “and they were very resentful of that.” Years later, as a historian, Shlaim “investigated this question.” He adds, “I didn’t want to just repeat conspiracy theories; I wanted to get to the bottom of the matter.”

While doing this research, he met an elderly friend of his mother, Yaakov Kirkouki, “who had been in the Zionist underground.” He told him about how they forged documents, including passports, and paid “bribes to officials to facilitate the movement of Jews from Iraq to Israel.” Kirkouki also told him that one of their members was a bright young man named Yosef Basri, a lawyer and “an ardent Zionist.” Basri and his assistant Shalom Salah Shalom “were responsible for three of the five bombs. Four people were killed by the first two bombs, which he found out from good Iraqi sources were planted by a young activist from the Istiqlal Party, the main party wanting to force the Jews out of Iraq (the only party that defended the Jews and a policy of democratic pluralism was actually the Communist Party). Four people died as a result of those two bombs, but the other three bombs only injured their victims.

Basri’s “controller” was Max Bennett, an Israeli intelligence officer based in Iran. That was a relatively safe context for Israelis because the Shah was pro-Western and Iran had “covert relations with Israel.” Bennett had given Basri the TNT for the bombs and the know-how to make them. The operation was not entirely successful, however. True, no one was killed and these explosions sowed a lot more fear within the Jewish Iraqi community. But Basri and his assistant were caught, tried (Shlaim thinks the trial was fair), convicted, given a death sentence and executed by hanging. Meanwhile, Bennett had been relocated to Cairo, where he was involved in several “terrorist attacks” in 1954. As Shlaim puts it, “Planting bombs in public places was to create bad blood between the Nasser regime and the West. So it was a false flag operation, like the false flag operations in Iraq in 1950-51.” But the last bomb went off prematurely and the entire ring was arrested, including Bennett himself, who committed suicide in prison. These events are known as the Lavon Affair (Pinhas Lavon was Israeli defense minister at the time).

What happened in Iraq and Egypt happened elsewhere as well. It was a pattern of what one expert called “cruel Zionism” “because it involved innocent Jews, decent Jews, good people, and the Zionist movement, or the intelligence officers, turned these Jews in Baghdad, and then later in Cairo, into . . . spies and terrorists against their own homeland. And these people paid the price.” These false flag operations especially turned the Egyptian population against the Jews. But this was 1954 and Nasser had succeeded in getting the British to sign a treaty by which they would withdraw their military and cease all other activities in Egypt. Israel resented this treaty, hence the false flag operations. “It was shortsighted,” says Shlaim. It failed to achieve its purpose and it created even more resentment between Egypt and Israel.

The shock of Arab Jews arriving in Israel

It wasn’t just the clash of cultures and language that greeted the newcomers from Iraq, Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East. Schlaim describes the attitude of the Ashkenazi elites as despising and ignorant of the Mizrahis and their cultural heritage. Upon entry into Israel, these people were sprayed with DDT, as if they were animals with deadly diseases. Then these 260,000 were put into tents with deplorable sanitary conditions and given food of poor quality. Perhaps worst of all, many of these camps were surrounded by barbed wire. Ironically, among these immigrants were teachers, lawyers, doctors and other professionals, yet the Ashkenazi transit camp managers considered them all backwards people. Of course, that’s what they thought of Arabs.

The identity issue pops up several times: they were mistreated because in some sense they were still the “Arab” enemy. Yes, they were Jews, but they were made to feel inferior to the Ashkenazis. So they were neither Iraqi nor Israeli, at least to a full extent. They were caught in between. Shlaim grew to admire all the construction and early achievements of this state being built from the ground up, but he felt like it was an Ashkenazi project he did not fully understand. He compares himself to Edward Said, the great Palestinian American literary critic and political activist, who entitled his autobiography “Out of Place.” This was exactly Shlaim’s experience. He never felt that he belonged in Israel. He could never shake his feeling of inferiority.

Shlaim’s views on Israel evolve after 1967

As mentioned in the beginning, his military service in the IDF between 1964-66 had made of him “an ardent nationalist and patriot.” But after the victory of 1967, Israel “became overtly a colonial power,” tripling its territory and building settlements in these conquered areas “in violation of international law.” This illegal activity has continued until the present time. For him personally, a sense of disenchantment came over him, but it took a few years for him to truly articulate it to himself. After much research and publishing, he came to the views he expressed in his magnum opus, The Iron Wall (2000; see the Updated and Expanded edition, 2014). It is almost 1,000 pages, but if you are interested, you might start with this excellent review, which includes a response from Avi Shlaim.

In the interview he says that he served “proudly and loyally” in the IDF when it was, as its name indicates (“Israeli Defense Force”), an army to defend its nation’s borders. But that changed after June 1967. It “became the brutal police force of a brutal colonial power.” Besides its purpose to defend Israel from any Arab belligerence, it now added a new task: “to police the occupation in the Palestinian territories.” Then he adds, “Today it’s really become a settlers’ army.” It doesn’t protect the Palestinians, but only the settlers. For instance, “When the settlers go on a rampage and there is a really disturbing, alarming escalation of settler violence against Palestinians, the army does nothing to curb them. On the contrary, it supports them.”

What does he think about the current protests in Israel? “In historical perspective, this is the most serious constitutional crisis that Israel has ever faced.” What is at stake, he explains, “is Israeli democracy and everything that goes with it, which is the rule of law, [and] the independence of the judiciary.” It’s a “frontal attack” on “the main symbol of Israeli democracy, the Supreme Court.” Yet that court is “no friend of the Palestinians” and it’s certainly not “a paragon of virtue” since it has routinely rubberstamped policies that can only be qualified as “apartheid policies” and “policies of ethnic cleansing.” Yet it retains some independence, both legally and in practice. It has at times declared a government policy illegal, forcing the executive branch to back down. This is no longer the case. The executive branch can now act with complete freedom and impunity. The protests will certainly continue and the army reservists who said they will not report for duty might well follow through. This is a dangerous time.

But what worries him most is that in Netanyahu’s present cabinet are extreme right-wing people with “an ethnonationalist agenda” that aims to achieve “Jewish supremacy.” Their true aim is “ethnic cleansing and annexation of the West Bank.” On the other side, the protesters make no mention of the Palestinians. Their only concern is “Israeli democracy and Jewish rights.” They represent the centrist parties that have no qualms about the oppression of Palestinians, though they claim to be less extreme. In fact, they support all the current settlements and Jerusalem as “the eternal, undivided capital of Israel.” Hence, as proponents of “liberal ethnonationalism,” they want to keep the status quo, which in fact is “an apartheid state.” They have no alternative to propose.

Shlaim believes in neither vision. Right-wing ethnonationalism and its liberal counterpart are equally dismissive of Palestinian rights, whether the million and a half Palestinian citizens of Israel or the 3 or 4 million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza living under military occupation since 1967. But Shlaim believes in democracy which is fundamentally about all citizens having equal rights. Here is what he wants to see: “I support one democratic state from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, with equal rights for all its citizens, regardless of religion and ethnicity.” Israel has “killed the two-state solution with its settlements.” The only solution for peace and prosperity of all is the one-state solution.

We’re now back to the story of his upbringing in Iraq. His family’s experience of coexistence within a diverse Iraqi society represents a hope that this kind of political, religious, cultural and ethnic pluralism can again be replicated in the Middle East – and this time in Israel. It may years from now, but Shlaim still hopes this will happen.

Please watch this. I also believe you will agree with me: the Middle East Eye journalist interviewing him is a young Iraqi Muslim (Mohamed Hassan). There’s another sign of hope right there.

[For more on my views of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, see my 2019 post “The Fight for Justice in Palestine”]

On September 16, 2022, the Iranian morality police arrested a 22-year-old Kurdish woman visiting relatives in Teheran likely because her hijab had slipped a bit over her head, showing some hair. Three days later, Mahsa Amini died in police custody, presumably from the beatings she received. Within days, dozens of Iranian cities in all parts of the country exploded in protests. These demonstrations continue, though much smaller now, almost five months later.

It’s hard to believe for those of us living in democratic nations – however imperfect that democracy might be – that these protesters, often women, and as young as 15, with the majority in their twenties, will still venture in the streets, or engage in public acts of defiance to voice their anger, when by now . . .

In this four-minute video in The Guardian from January 23, 2023, the journalist tells us that these executions have made protestors even more angry and even more determined to continue their fight for freedom, even if it costs them their lives. A protestor on death row put it this way, “What they’ve done, the regime with their executions, is that they’ve created this fire under the ashes.”

First, allow me to present some historical background. There’s a long genealogy of public resistance to the Iranian theocratic regime, but it flared up dramatically in this century.

The four protest movements since 2009

The first was arguably the greatest, in terms of participation. The Green Movement, named for the green sash previous President Mohammad Khatami gave to reform candidate Hossein Mousavi in the months running up to the June 12, 2009 presidential election. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was running for a second term and won, but from the start the opposition believed the vote had been fraudulent (it turns out that it was, as the UK’s Chatham House, among other studies, proved). Quoting again from the Iran Primer, “The Green Movement reached its height when up to 3 million peaceful demonstrators turned out on Tehran streets to protest official claims that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had won the 2009 presidential election in a landslide. Their simple slogan was: ‘Where is my vote?’”

But over the fall, under Hossein Mousavi’s leadership (a cleric, he had been prime minister in the 1980s), the movement “evolved from a mass group of angry voters to a nation-wide force demanding the democratic rights originally sought in the 1979 revolution, rights that were hijacked by radical clerics.” But by the beginning of 2010, the regime had cracked down so brutally, that Mousavi and his leaders had to call off any more public protest. Still, particularly among the students, protests had loudly called for Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to step down. One often heard the crowd chant, “Death to the dictator!”

An October 26, 2022 interview with respected Iranian American sociologist Asef Bayat (University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign) was first conducted in Farsi and was “widely shared in Iran – and now banned by the Tehran authorities.” New Lines Magazine republished it in English under the title, “A New Iran Has Been Born – A Global Iran.” Bayat brings up the 2009 Green Movement and notes that it “was largely a movement of the urban modern middle class, though some other discontented people also supported it.” The uprising of 2017, by contrast, was more about the poor protesting their impossible life conditions, but they remained separate groups demanding better conditions, “like unpaid workers, creditors, drought-stricken farmers and others rose up in protest simultaneously throughout the country, but each raised their own sectoral demands.”

Two years later, this wave of discontent found greater unity. The uprising of 2019 was a more cohesive movement of middle-class poor and other marginalized people from cities and the provinces protesting “economic and cost-of-living issues.” And in some cases, the tactics they used were “quite radical.”

But, argues Bayat, “this current uprising has gone even further.” He explains:

“It has brought together the urban middle class, the middle-class poor, slum dwellers and people with different ethnic identities — Kurds, Fars, Azeri Turks and Baluchis — all under the message of ‘Woman, Life, Freedom.’ Significantly, this is an uprising in which women play a central part. These features distinguish this uprising from the previous ones. It feels like a paradigm shift in Iranian subjectivities has occurred; this is reflected in the centrality of women and their dignity, which relates more broadly to human dignity. This is unprecedented. It is as though people are retrieving their ruined lives, perished youth, suppressed joy and a simple dignified existence they have been denied. This is a movement to reclaim life. People feel that a normal life has been denied to them by a regime of elderly clerical men. These men, they feel, seem so separated from the people and yet they have colonized their lives.

The current wave, sparked by Mahsa Amini’s brutal death, is the fourth since 2009. It was not just set aflame by the death of a young woman; it was and continues to be a movement inspired and led by women.

The persistent role of women

Suzanne Kianpour, “an Emmy-nominated news reporter and producer,” is only 36 but has reported from Washington, Los Angeles, Beirut and London, and most recently produced the “Women Building Peace” series for the BBC. As a “Persian and Sicilian” American who speaks and writes fluently in Farsi, she has leveraged her intercultural background and journalistic experience to cover stories in over fifty countries and interviewing some high-profile leaders, including the Iranian foreign minister (see her website). I only mention this as background to the piece she wrote for Politico magazine (Jan. 22, 2023), “The Women of Iran Are Not Backing Down.”

She starts off by recalling an incident while visiting her cousin in Tehran in 2007 while a student. She witnessed a young woman being dragged off the street into a morality police van. Then she adds,

“Fifteen years later, the morality police took it too far. In September 2022, during what seemed a typical detention over an inadequate hijab, Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish woman visiting Tehran, was arrested and beaten. She subsequently died in custody. Two female journalists broke the story. They are now in prison. The country erupted in widespread protests not seen since the Green Revolution of 2009, demanding justice for Mahsa and freedom and civil rights for all women.”

Protests have taken place over the years in Iran, “over election fraud, economic woes, civil liberties.” Yet this time feels very different, Kianpour contends: “an unprecedented revolution led by women, with support from men, encompassing a wide variety of grievances, all laid out in the heart-wrenching Persian lyrics of Shervin Hajipour’s song ‘Baraye,’ or ‘because of.’ It’s become the anthem of the revolution, striking such a nerve around the world that backlash after Hajipour’s arrest led to his release.” This song won a Grammy award, in fact the very first for Best Song for Social Change Award (watch Jill Biden present it at the Grammys).

Catherine Z. Sameh, associate professor of gender and sexuality studies at the University of California, Irvine, reminds us that the Islamic Revolution, unlike the Shah regime, noticeably benefited the rural, working class, and poor women who had been left behind. Through its comprehensive social welfare programs, literacy levels and life expectancy went up for women, as well as the number of women in Iranian universities. Women also began to have fewer children as the poverty rate was falling. However, she notes, “these improvements were exacted at a very high cost for women: a discriminatory legal structure that legitimizes patriarchal control over and violence against women and girls.”

What are some of these “discriminatory” laws”? Here are a few: a citizenship status conferred on children only through the father; custody of children more easily granted to the father; inherently patriarchal family laws related to marriage and divorce. Kianpour adds a few more: “Women are forced to cover their hair in hijab and bodies in loose clothing. They cannot dance publicly, cannot drive motorcycles and cannot travel without parental or spousal approval.” They are not admitted in sports stadiums either.

Women over the decades, at least in some circles, have often quietly resisted this oppressive system aimed at controlling their persons and bodies. But in the 2000s, they started to speak out. Sameh describes the 2006 One Million Signatures Campaign launched by women activists both inside and outside Iran. Both the Qur’an and the Iranian revolution promised equality for women but reality turned out quite differently. Hence, they presented 46 articles in Iran’s Civil Code and Penal Code that plainly discriminated against women. Going door to door, organizing both house and public meetings, they sought to build a movement of dialogue and consensus building starting at the grassroots. The signatures collected helped to show that anyone and everyone’s voice is counted.

The movement’s co-founder, Noushin Ahmadi Khorasani, explained their rationale: “The power of the civil and democratic movement of the Iranian people must come not from blood, clenched fists, bulging veins, and zealous revenge-seeking, but rather from life-affirming endurance, persistence, and thoughtfulness.” Sameh calls this “a politics informed by feminist principles and organizational practices of collectivity, dialogue, and a deep embeddedness in the ordinary lives of people.”

In fact, she argues, this “might well be the unfolding of a distinctly new kind of feminist revolution.” It’s extraordinary, really. Sameh is worth quoting here:

“In the streets, schoolyards, universities, restaurants, shops, and homes of Iran, women and girls are demanding their freedom and autonomy and, in the process, creating relationships based on mutuality, solidarity, love, and care. Unlike their predecessors, however, they are not interested in negotiating within the parameters set by a patriarchal authoritarian state. In the multiple and extraordinary acts of celebration and defiance—removing and burning hijabs, dancing in the streets, eating in restaurants without hijabs, graffitiing walls, kissing in public, creating art, singing, cutting hair, taping sanitary napkins over surveillance cameras—women and girls are occupying space with their bodies and creating a new world of political symbols, ideas, practices, and visions.”

Why the slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom?”

As quoted above, Noushin Khorasani described the One Million Signatures Campaign as women continuing the revolution very differently than the men had it in the past – “from blood, clenched fists, bulging veins, and zealous revenge-seeking.” Enough of that misapplied testosterone, she says. What is needed is an injection of “life-affirming endurance, persistence, and thoughtfulness.” Sameh had begun her essay with these words:

“The feminist uprising in Iran—sparked by the beating, arrest, and death in police custody of Mahsa (also known by Jîna) Amini, a young Kurdish Iranian woman accused of “improper hijab”—is generating previously unimagined ideas, images, and possibilities. The current movement, led by women and girls, has forced us all to rethink the glorified figure of the revolutionary as a militant, often militarized, and individual masculine subject. It also invites us to understand the complex history of women’s struggle in Iran—not as counterpoised to or lagging behind Western feminism, but rather on Iranian women’s own terms.”

Notice that Mahsa Amini’s other name is “Jina,” meaning “life.” The current revolutionary movement, as mentioned above, is about girls and women demanding their civil rights of “freedom and autonomy,” but only in a way that creates “relationships based on mutuality, solidarity, love, and care.” Recall that sociologist Asef Bayat had claimed, “This is a movement to reclaim life.” The quest for freedom is about life and human flourishing.

This reminds me of the time we lived as a family in the West Bank just outside of East Jerusalem in the 1990s. The Oslo Accords rolled in with great hope for Palestinians, but were soon dashed, as military checkpoints appeared out of thin air constraining Palestinian life even more than before. Already, it was clear that the Israelis had no intention to back down from their military occupation of Palestinian territories and that the establishment of the Palestinian Authority was only a sham, an insidious scheme to pacify a people in order to better subjugate them. Under those conditions, violence is bound to erupt. With horror, we witnessed several suicide bus bombings in Jerusalem (West Jerusalem, the Jewish side, much larger and more prosperous). At the time, we were actually part of a support group for parents of ADHD children, in which we were the only non-Jews. We saw up close the fear, anger and grief of Israelis.

We also saw women coming together from both sides, calling themselves “Woman in Black.” These Israeli and Palestinian women would stand at a busy Jerusalem intersection in West Jerusalem at noon on Fridays (Israelis are rushing to get ready for Shabbat so traffic is intense). They held up signs communicating the following message: “violence is not the way; we all mourn these senseless killings; only dialogue and mutual understanding will bring peace.” Since time immemorial, it is the men who start wars and kill. Today in many places, it is often the women who come together to seek reconciliation and peace (see my blog post about the 2019 women-led protests in Sudan).

Whence Iran?

I began this post with the sheer brutality of the theocratic state’s repression of this protest movement. Kianpour notes that “[t]he Islamic Republic’s atrocities have gotten global attention and led to Iran being kicked off the UN Commission on Women.” She also quotes the “Iranian-born British actress and activist Nazanin Boniadi” who in October “met with Vice President Kamala Harris and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan at the White House to discuss how the Biden administration can help protesters with internet freedom and hold the Islamic Republic accountable for human rights abuses.” Boniadi stated:

“The most unprecedented thing we’re seeing is people are fighting back against security forces. Women are not just taking off their headscarves in protest, they’re burning them. And young kids, young girls are protesting . . . Despite the brutal crackdown, they’re showing no signs of slowing down. I think this is a historic moment, I truly believe this is the first female-led revolution of our time.”

But will it topple the clerical regime of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei? In a short interview conducted by Ali Shapiro of NPR with Columbia Senior Advisor Kian Tajbakhsh, the latter had this to say about it:

“… authoritarian systems are remarkably resilient in the face of opposition. I mean, the experts who look at authoritarian regimes point to three pillars of regime strength – a cohesive ruling elite, a highly developed, loyal coercive apparatus and the destruction of rival organizations and alternative centers of power. Looking at those three, what is very striking is how these all seem to be intact. So unfortunately, it's hard to see them crumbling in the next six months or so.”

But when Shapiro asks him whether some image or moment sticks with him from these months of protest, Tajbakhsh seems more optimistic. That young men, he answers, stand publicly with these young women is “absolutely uplifting” for him. That kind of solidarity “bodes well for the future.” He adds, “It'll be very hard for them to go back into their families and into their houses and even to their own marriages, let's say, or their partnerships, and treat women in a more traditional and discriminatory way. So I think that these protests have thrown down a gauntlet. It's a moral challenge to this regime.”

I end with James Dorsey’s analysis of a recent poll among Iranians in Iran and abroad conducted by the Netherlands-based Gamaan Institute with the help of Voice of America and London-based and Saudi funded Iran International TV. The outcome was stunning, even if the participation of Iran International might have skewed some of the results: “an overwhelming majority of the 158,000 respondents in Iran and 42,000 Diaspora Iranians in 130 other countries, rejected Iran’s Islamic regime. The poll was published days before Iran commemorates the 44th anniversary of the 1979 Islamic revolution.”

To the question, “Islamic Republic: Yes or No?,” 80.9 percent in Iran said no. Among the diaspora, the figure was 99 percent. When respondents in Iran were asked whether they supported the anti-government protests, 80 percent said yes; when asked if they would change anything, 67 percent said they would.

Within Iran, it is striking to see the level of participation. If, as Kianpour puts it, it’s fair to say that Gen Z “are the true leaders of the revolt,” many others support it. Dorsey highlights the following from that poll:

“Twenty-two per cent of those in Iran said they had joined the protests, including participating in nightly chanting against the government; 53 per cent indicated they might. Thirty-five percent had engaged in acts of civil disobedience like removing headscarves or writing slogans; 44 per cent participated in strikes, and 75 per cent were in favour of consumer boycotts. Finally, eight percent said they had committed acts of ‘civil sabotage’ while 41 per cent suggested they might.”

Eighty-five percent of respondents believed the opposition should organize, preferably around some kind of “solidarity council or a coalition of opposition forces.” Then, in terms of next steps, “[f]ifty-nine percent expected the council to establish a transitional body and a provisional government.”

But it gets a bit murky when you go into details. It turns out that the top candidate to join such a council is “Reza Shah Pahlavi, the Virginia-based son of the toppled Shah.” Though 22 percent in Iran and 25 percent outside preferred a constitutional monarchy, 28 percent inside Iran and 32 percent outside leaned toward a presidential system. Fewer preferred a parliamentary system (say, like Britain).

In the end, we cannot say that the current wave of protests will actually topple the Islamic Republic, which requires that its Supreme Leader be an ayatollah. NPR reporter Mary Louise Kelly just spent a couple of weeks in Iran and filed this report (Feb. 16, 2023). The street protests have been mostly tamped down, but students interviewed said they will start up again. One female student studying psychology said, “This kind of dissent . . . it doesn’t go away.”

But it’s worth emphasizing: this is not a revolution against Islam, like the French Revolution was against the Catholic Church (allied with the monarchy) and Christianity. Rather, it’s a revolt against the traditional, male-dominated interpretation of Islamic law that robs women of their civil and personal status rights. It is also a full-throated demand for democracy – in the way I was explaining it in the context of the UN’s Sustainable Development goal #16:

“A democratic system is one in which its institutions and the mechanisms that keep them functioning (including voting, which isn’t spelled out here) are actually considered “inclusive and responsive,” and one in which those serving in the legislatures, public service, and the judiciary, reflect the population as a whole ('by sex, age, persons with disabilities and population groups').”

Is this kind of holistic human flourishing that controversial? In many parts of the world ruled by authoritarian regimes, it seems out of reach. In Western cultures too, especially with their strong emphasis on individualism, whole segments of the population can be left behind. Clearly, this “inclusive and responsive” democracy is a challenge for all societies.

In this light, I urge people of faith in particular to get behind this kind of feminist-inspired, grassroots movement of “creating relationships based on mutuality, solidarity, love, and care.” It’s about human dignity, first and foremost. Maybe it will still take a while to get there in Iran (or in the US, for that matter), but as Kianpour concludes, these young people have sacrificed so much to call for a change. They won't stop: “This genie cannot and will not go back in the bottle.”

Afterword (3/25/23): Asef Bayat published an in-depth article in the March 2023 edition of the Journal of Democracy. His concluding paragraph nicely summarizes this 4900-word piece:

"Whatever the endgame, a lot has changed already. Things are unlikely to go back to where they were before the uprising. A paradigm shift has occurred in the Iranian subjectivity, expressed most vividly in the recognition of women as transformative actors and the 'woman question' as a strategic focus of struggle. Most Iranians now want a different kind of government. A discursive shift away from religion has been combined with a strong anticlericalism and resentment of state religion. New norms have been established on the ground and are likely to stay. The morality police, forced hijab, and sex-segregation in public might be things of the past. The once lethargic society plagued by a sense of impasse has gained a new energy. After years of anguish and despair, a kind of uncertain hope has emerged, a vague belief that things might really change for the better. Those who expect quick results will likely be dispirited. But the country seems to be on a new course. The people’s drive to live in dignity has thrown a wrench into the machine of subjugation. A new, though unknown, opening may well be on the horizon."

As you know, the G20 represents the twenty most powerful economies of the world and it meets every year. With a rotating leadership, Indonesia is the 2022 convener this month, and President Joko Widodo has insisted that President Vladimir Putin attend (he did not in the end). Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov had walked out of the G20 ministers conference in July as a result of Western nations’ fierce criticism of the Russian war in Ukraine. So far, Widodo’s entreaty to the G7 leaders to join regardless of Putin’s presence has succeeded to keep the G20 on track.

But Widodo’s objectives are even more ambitious than that. For the first time, Indonesia’s powerful Nahdatul Ulama organization (NU) – by far the world’s largest civil society Muslim organization (90 million members) – has initiated a two-day parallel religious conference called the Religion 20 Forum (R20) (Nov. 2-3) and has allowed the Saudi-run Muslim World League (MWL) the chance to co-sponsor it. There is a lot to unpack here. Let me begin with Indonesia and the NU organization.

Indonesia and the Nahdatul Ulama

Indonesia is the most populous Muslim-majority nation (231 million). The second is Pakistan (212 million); third, India (200 million); fourth, Bangladesh (154 million); fifth, Nigeria (nearly 100 million). And simply being part of the G20 makes Indonesia even more influential. Add to that an Asian culture that favors social harmony over ideology and creed, and an Islamic heritage that tolerated at least some room for its traditional mix of Hindu and native rituals and practices.

The twentieth century witnessed a revival of Islam, no doubt sparked by the harsh reality of colonialism and by other influences of global Islam at the time. Two reform movements were founded in the 1920s that are unique to Indonesia and remain very influential today. The Muhammadiyya movement borrowed many features of the Islamic modernism of 19th-century pioneered by Middle Eastern scholars and activists Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh. Their main insight is that Islamic law has to be reformed with more place given to reason. Its membership today is around 40 million.

The second organization remained until recently more traditional in its approach, while always seeking reform. Nahdatul Ulama means “Awakening (or Renaissance) of the Islamic Scholars.” Both organizations have established a network of pesantrens (residential religious schools for the youth) and universities, and continue to run multiple clinics and hospitals.

Yet in this century, NU has gradually paid more attention to the deradicalization of some of its youth and to the possible root causes of violent Islamic extremism, which has also been plaguing Indonesia. With the election of Yahya Cholil Staquf as chaiman of the NU Executive Council in 2021, NU took an even stronger stand against Islamic militancy and a bold push for democracy at every level of society. In a 2021 OpEd in the Wall Street Journal, Staquf tells of a recent speech he made at the United Nations on Islamic terrorism. He argued that the violence of al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, Boko Haram and other terror groups finds support from some traditional Islamic teachings. In particular, . . .

“. . . the doctrine, goals and strategy of these extremists can be traced to specific tenets of Islam as historically practiced. Portions of classical Islamic law mandate Islamic supremacy, encourage enmity toward non-Muslims, and require the establishment of a universal Islamic state, or caliphate. ISIS is not an aberration from history.”

Staquf went on to explain that until the end of the Ottoman caliphate in 1924 Muslim lands were ruled under the classical formulations of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), which many people wrongly conflate with Sharia. That is unfortunate, he said, because the scholars’ interpretation of the sacred texts (Qur’an and Sunna, hence Sharia, as opposed to fiqh) had created and reinforced over time a political ideology of Islamic supremacy that discriminated against religious minorities and glorified war as a way to expand political power and national borders. Fiqh, by definition, is a human interpretation and practical application of the Sharia in a particular context in a particular time. As such, it is fallible and in constant need of revision.

For instance, beyond the many rulings of fiqh that give more power to men and take away rights from women, “Classical Islamic orthodoxy stipulates death as the punishment for apostasy and makes the rights of non-Muslims contingent on a Muslim sovereign’s will, offering few protections to nonbelievers outside this highly discriminatory framework.” Then Staquf adds, “Millions of devout Muslims, including many in non-Muslim nations, regard the full implementation of these tenets as central to their faith.”

As mentioned above, this attachment to traditional Islamic jurisprudence is especially problematic when it can be used to justify violence done to non-Muslims and other Muslims. This is the core of his OpEd argument:

“The problem is that these tenets, which form the core of Islamist ideology, are inimical to peaceful coexistence in a globalized, pluralistic world. But we can’t bomb an ideology out of existence. Nearly 1 in 4 people in the world is Muslim, and many Muslims—me included—are prepared to die for our faith.

The world isn’t going to banish Islam, but it can and must banish the scourge of Islamic extremism. This will require Muslims and non-Muslims to work together, drawing on peaceful aspects of Islamic teaching to encourage respect for religious pluralism and the fundamental dignity of every human being.”

Catholics and Protestants routinely killed each other up until the 18th century, Staquf notes. But then they reformed their theology to see each other as fellow human beings and, especially, as fellow Christians. Muslims today can to the same with their theology, which like their Jewish counterparts, is closely tied to their jurisprudence. NU is doing this very thing, discarding elements of fiqh that stand in the way of pluralism, “universal love and compassion,” and adopting the Nusantara Manifesto: “a theological framework for the renewal of Islamic orthodoxy—and abolished the legal category of “infidel” within Islamic law, so that non-Muslims may enjoy full equality as fellow citizens, rather than endure systemic discrimination and live at the sufferance of a Muslim ruler.” Staquf and his colleagues also call this “Humanitarian Islam.”

The Nusantara Manifesto (2018, see above link to download the 40-page pdf document) has a version of this in its opening and concluding paragraph:

“The Nusantara Manifesto represents a significant milestone within a long-term, systematic campaign—guided by the spiritual leadership of the world’s largest Muslim organization— designed to block the political weaponization of Islam, whether by Muslims or non-Muslims, and to curtail the spread of communal hatred by fostering the emergence of a truly just and harmonious world order, founded upon respect for the equal rights and dignity of every human being.”

How could such a radical reinterpretation of Islamic theology and law be in any way compatible with the puritanical and exclusionary ideology of the Saudi state (Wahhabism)? Mind boggles . . . and yet . . .

The surprising NU outreach to the Muslim World League

This “recontextualization of Islamic theology,” on the face of it, would be anathema to the Muslim World League (MWL), which since its inception was a propaganda tool of the ultraconservative Saudi religious ideology of Wahhabism. To be sure, the Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (known as MbS), has embarked on some cosmetic reforms like allowing women to drive and attend public football matches, and the youth to experience some Western-style entertainment. He also put the moral police on a much shorter leash. But none of that amounted to religious reform. As James M. Dorsey, incisive commentator on global Muslim affairs, put it, “Instead, it amounted to long overdue social change by decree.”

This deceptive window-dressing campaign is likely why the MWL jumped on the NU’s offer to jointly chair the R20. Dorsey ponders the relative advantages both sides saw in this partnership:

“Persuading the League to endorse a genuinely moderate form of Islam would have enormous significance. It would lend the prestige of the Custodian of Islam's two holiest cities, Mecca and Medina, to Nahdlatul Ulama's effort to reform Islam. That, however, is a long shot, if not pie in the sky.

More likely, the League sees reputational benefit in its association with Nahdlatul Ulama. The League also probably hopes to co-opt the Indonesian movement to prevent it from becoming a serious competitor for hearts and minds in the Muslim world.

Neither group may succeed in fulfilling its aspirations.

Nahdlatul Ulama has a century-long history of fiercely defending its independence and charting its moderation course.

At the same time, there is little reason to believe that the League can embrace anything but what Mr. Bin Salman authorises.

If the last two months provide an indication, Mr. Bin Salman and his loyal lieutenant, League secretary general Mohammed al-Issa, can, at best, be expected to opportunistically pay lip service to Humanitarian Islam.”

Dorsey’s comment about “the last two months” was a reference to the crown prince’s hard line when it comes to stamping out all political dissent in the kingdom. In fact, it seemed MbS saw President Biden’s July 2022 visit to him in Jeddah as a green light to quash even more fiercely any sign of protest under his de facto rule. To wit, 34-year-old mother of 2 young boys, Salma al-Shehab, was working on a PhD in Leeds, UK and decided to visit her family for the holidays in Saudi Arabia in December 2020. She was then arrested and handed down a 34-year prison sentence for following overseas Saudi dissidents on Twitter and retweeting some of their tweets. Apparently, this qualifies as threatening the integrity of the state. She is still in prison, alleging “abuse and harassment.” Since then, another Saudi woman, Nourah Bint Saeed al-Qahtani, was arrested and given a 45-year sentence for “using the internet to tear [Saudi Arabia’s] social fabric.” MbS is obviously seeking to make an example of these women and sow terror among his would-be detractors.

Then just last month three members of the Howeitat tribe were put on death row for resisting an edict that forced them to leave their land to make way for the construction of Mr. bin Salman’s US$500 billion futuristic Neom megacity on the Red Sea. Civil rights, it seems, shine by their absence in Saudi Arabia.

Clearly, Dorsey’s comment about NU’s pluralism and democratic ideals rubbing off on the MWL as “pie in the sky” is understandable. Yet the crown prince knows very well that oil money will be drying up and he has sought to diversify the KSA economy. He has not pursued tourism as aggressively as his ambitious neighbor, UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, but in order to attract more business capital, both neighbors promote a “moderate Islam” that supports autocratic regimes like their own. That said, the UAE is open to at least a degree of religious pluralism in its realm, permitting, for instance, the building of churches in Abu Dhabi. Its Saudi neighbor, by contrast has never allowed such a thing.

A quick side bar on the UAE is warranted here, because despite sharing with the KSA a mission to defend autocratic governance on Islamic terms, it competes with its neighbor for economic, political and religious soft power in the Arabian Gulf and in global capitals. But it’s a game the Emiratis appear to be winning so far.

Dorsey posted a recent piece on the UAE’s top religious cleric, Abdullah Bin Bayyah, whose global influence could be seen in the 2016 Marrakesh conference in Morocco, where over 250 Muslim religious leaders, scholars and even some heads of state spoke out against the persecution of Christians and Yazidis under ISIS. The Marrakesh Declaration was notable for its ringing endorsement of religious freedom. But as Dorsey rightly points out, democracy is not on the table for Mr. Bin Bayyah:

“In Mr. Bin Bayyah's mind, autocracy, uninhibited by religious jurists who do not know their proper place, is best positioned to ensure societal peace. Mr. Bin Bayyah remained silent when his Emirati paymasters rendered his theory obsolete with military interventions in Libya and Yemen. The interventions fueled civil wars while political and financial support for anti-government protests in Egypt that overthrew the country’s first and only democratically elected president in 2013 produced a brutal dictatorship.”

NU versus MWL: justice as rights versus traditional fiqh

Quoting from Yahya Cholil Staquf’s OpEd above gave you the impression that his main objective was dismantling the scourge of Islamic-related extremism and violence. But he also demonstrated that this ideology was fed in part by the traditional worldview of Islamic jurisprudence (the world being divided between the Abode of Islam and the Abode of War; hence, by military means—by using the “lesser jihad”—we can expand the borders of Islam until, God willing, it encompasses the whole world). Therefore, a bold and clear-eyed revamping of classical Islamic fiqh is in order. It includes not only eliminating any tacit support for military action in order to advance God’s cause, but also a number of issues that until now justify the discrimination against women’s rights, religious minority rights, and bolster autocratic regimes that suppress the rights of citizens to choose political leaders to represent them. In other words, the KSA and the UAE’s bid to spread their top-down, monarchical form of “moderate” Islam, with an ulama class subservient to the ruler’s every wish, will not succeed if the NU has its way.

So how did the inaugural R20 proceed? According to the British Religion Media Centre’s report, over 300 religious leaders came from around the world. Shaykh Abdullah Bin Bayyah was one of several keynote speakers, but the article features MWL secretary-general Muhammad bin Abdul Karim al-Issa right from the start, indicating that he is also a Saudi politician, “widely regarded as moderate, challenging extremism and promoting peace, dialogue and respect.”

Words are cheap, as they say, but in an interview with the Religion Media Centre Dr. al-Issa offered a judicious remark about the passing of the baton to India, next year’s host of the G20 and now the R20. As many conflicts today have roots in religious identity, he noted, “conflict resolution and peace building must involve society’s moral and faith leadership.” Since the Hindu nationalist organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was prominently represented in this conference, Shaykh al-Issa, while affirming clearly India’s right to select its own delegates for next year’s forum, he also cautioned that “it is better to communicate than create a void where misunderstandings accumulated.” Keep in mind that RSS people are the ones primarily responsible for attacks on Muslims, destructions of their homes and shops by bulldozers, with these tensions spreading into the Indian diaspora in the West. Here I can see the MWL playing a constructive peace building role.

But when it comes to democratic ideals grounded in the human rights of all human beings as stipulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its subsequent covenants, I am afraid that statements made by the likes of al-Issa and Bin Bayyah are more about gaining soft power and cleaning up their reputations. NU’s Humanitarian Islam, by contrast, has embarked on a courageous plan to reform traditional Islamic jurisprudence. That is not what these men have signed up for.

Still, after all this reading and pondering about the very first R20 and its launching by NU with the support of Indonesia’s president Joko Widodo (who spoke at the R20), I come away encouraged that this momentum will likely produce change in the long run. One reason is the clarity of the goals established from the onset by NU. The Final Communiqué (available in this article) bears this out. The final goal says it all: “foster the emergence of a truly just and harmonious world order, founded upon respect for the equal rights and dignity of every human being.” As I wrote in my book on justice and love, justice is about rights and it leads to a society in which everyone finds their place and are able to flourish – yes, and able to have a political voice.

Second, the most prominent speakers listed by the MLW on its news website. In order they are (notice NU comes after MLW):

Pope Francis also addressed the assembly in a recorded statement. Bin Bayyah appears (with typo), but in his connection to an NGO he helped to found. There are no Orthodox Christian leaders, but we find the Vatican represented along with the Iraqi Chaldean Catholic Church, the top Anglican leader in Africa, the leader of the World Evangelical Alliance representing 600 million followers globally, and finally, a Shinto, a Hindu and a Latin American Jewish professor. Many others were there also. See in particular this short video promoting the participation of the Mormon leader. It will give you a better feel for the pageantry of such occasions. [See also this 45-second Instagram montage of the handover ceremony to India]

But one thing is for sure. We should all applaud any initiative that seeks to make religion a solution to our world’s many problems, while condemning the many ways it has contributed to violence and oppression. We are in the debt of Indonesia’s Humanitarian Islam.

On October 8, 2022, I presented a paper at the annual meeting of the Evangelical Missiological Society. It was a joint session with the International Society for Frontier Missiology and the paper’s title is, “Caring about Global Governance for the sake of Human Flourishing.” This was an opportunity for me to put on paper some of the material I have been working on for my book on Christian mission and human flourishing. I had already posted a two-part blog post related to this topic (“The New Economy and the SDGs”), but this was the opportunity to ground this project more specifically in mission theology.

In particular, this paper highlights some of the interviews I have been conducting with Christians actually involved in some aspect of global governance. Following John Kirton of the University of Toronto, I have defined global governance as including the plurilateral summit institutions (PSIs like the G7/G8, G20, BRICS); the many United Nations summits on specific subjects, but especially the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Summit on Climate Change, both in 2015; intergovernmental and multilateral agencies like the World Bank and regional ones like the EU, the African Union, etc.; and finally, NGOs, both in the business and development communities, and more broadly, civil society. All are stakeholders trying in one way or another to eradicate poverty and build a more peaceful and just world.

Yale University Press has finally released this translation I made of Tunisian Islamic scholar, activist and politician, Rached Ghannouchi's classic work, Public Freedoms in the Islamic State.

I rarely get so absorbed by a book I’m reading. But I could hardly put down Ronald F. Inglehart’s 2021 book (Religion’s Sudden Decline: What’s Causing it, and What Comes Next?). An emeritus professor of political science at the University of Michigan, Inglehart is the “Founding President of the World Values Survey Association, which since 1981 has repeatedly surveyed representative national samples of the publics of 108 countries containing over 90 percent of the world's population” (from the Amazon page). This means he has been doing this kind of research with a couple hundred of other international social scientists for 40 years and has closely followed the evolution of people’s values and ethical norms around the globe. He died last year and this memorial page notes that according to Google Scholar he is the most quoted political scientist.

Inglehart’s findings surprised me – I’ve long known that people from all the major religions got more “religious” starting in the 1970s. In fact, I delved into that phenomenon using the sociology of religion in 2011, asking, “Is ‘Fundamentalism’ Still Relevant?” I stand by that still today.

But the general resurgence of religion last century began to reverse itself in the new millennium. The key year is 2007. In his first book on this topic, co-authored with Harvard University’s Pippa Norris (Secular and Sacred: Religion and Politics Worldwide), he hadn’t seen this dramatic change yet (first edition, 2004, second in 2011). What they did find is that for the 49 countries “for which substantial time series data was then available . . . more than two-thirds of [these] countries . . . showed rising religiosity in response to the question ‘How important is God in your life?’” (14).

[Allow me to insert a brief parenthesis here. Noted Baylor University historian of religion Philip Jenkins offered some thoughts about Inglehart’s book on his blog (Anxious Bench/Patheos) in May 2021. It’s a book “that I have been devouring,” he wrote. Just a year before, Jenkins had published a book offering very similar conclusions, Fertility and Faith, but from a different angle:

“High-fertility societies, like most of contemporary Africa, tend to be fervent and devout. The lower a population’s fertility rates, the greater the tendency for people to detach from organized or institutional religion. Thus, fertility rates supply an effective gauge of secularization trends.”

Jenkins is also struck by the similarity of their findings: “In the US context, we both highlighted 2007 as the critical transition point. The gargantuan economic crash of that time is an obvious culprit.” I end here the parenthesis, but in highlighting again how significant this convergence of views is from two scholars coming from different perspectives and disciplines.]

Now back to Inglehart. He and Pippa had found that among 49 countries two-thirds had become more religious from 1981 to 2007. That said, respondents in most high-income countries exhibited a decline in religious belief and practice, while those that exhibited the most growth in religiosity were six former communist countries (13 out of 15 of those nations showed at least some growth).

Now writing in 2021, Inglehart explains his surprising new findings:

“The results show that dramatic changes have occurred since 2007 in the same countries analyzed earlier. In sharp contrast with earlier findings, which showed the dominant trend to be rising religiosity, the data since 2007 shows an overwhelming trend toward declining religiosity. The public of virtually every high-income country shifted toward lower levels of religiosity, and many other countries also became less religious. The contrast between ex-communist countries and the rest of the world was weakening, but still the eight countries showing the largest shifts toward increasing religiosity from 1981 to 2020 were ex-communist countries” (14, emphasis his).

The year 2007 also proved a watershed for the United States and its hitherto status as the only high-income country to be significantly religious. In fact, the US “once constituted the crucial case supporting the claim that modernization need not bring secularization.” Advocates of the “religious market secularization theory” could point to a very diverse and competitive religious landscape – the one factor which for them explains religious vitality. But that now seems irrelevant: “The U.S. still has plenty of diversity, but it recently has been on the same secularizing trajectory as other high-income countries; indeed, since 2007 it has been secularizing at a more rapid pace than any other country for which data is available” (83). My title above (using “precipitous” instead of Inglehart’s “sudden”) applies particularly to the United States.

Here are some of the indicators (emphasis mine):

Why does Inglehart (and Norris – this book builds on the same theory as his co-authored book) believe this is happening?

Inglehart’s “evolutionary modernization theory”

Inglehart is a social scientist, and as such, he is careful to note that the presence of contextual factors also help to explain why a nation (or block of nations) waxes or wanes in its religiosity – including historical, political, religious and social factors. One example he gives is the much faster growth of capitalism in northern Europe compared to its southern Catholic counterpart in the three centuries after the Reformation. Partially looking at Max Weber’s work on the Protestant ethic, Inglehart surmises that Martin Luther’s emphasis on individual Bible reading, and thereby literacy and scientific study, were determinative in providing Protestant nations with a “remarkable economic dynamism.” By 1940, “people in Protestant countries were on average 40 percent richer than the people of Catholic countries” (22).

Yet his main point here is that even with a sharp drop of religious belief and practice, religious ethical norms can still remain dominant within particular populations. This seems to be at least a part of the success of “the Nordic countries”: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland (he adds The Netherlands and Switzerland in most charts and calls this bloc “Protestant Europe”). These nations rate consistently highest as a group according to many indicators, such as life expectancy, years of schooling, GDP per capita, and life satisfaction. But it’s more complicated than that, he explains:

“The Nordic countries seem to be at the cutting edge of cultural change, and their distinctive character seems to reflect a synthesis between the Protestant ethic and the welfare state. As Chapter 2 demonstrated, Protestantism left an enduring imprint on the people who were shaped by it. But the Social Democratic welfare state that emerged in the Nordic countries in the 20th century modified this heritage by providing universal health coverage; high levels of state support for education, extensive welfare spending, child care, and pensions; and an ethos of social solidarity” (107-8).

He then adds, “These countries are also characterized by rapidly declining religiosity.” This brings up his central argument, which connects to Philip Jenkins’ linking of fertility and religious fervency. Two cultural shifts were underway in the 20th century, but converged early in the 21-century to form a “tipping point” – meaning that this cultural change changed directions and accelerated dramatically:

For an arresting case study, see this short piece by Philip Jenkins in The Christian Century: “How Quebec went from one of the most religious societies to one of the least.” In the 1950s, 90 percent of the population attended Mass. Today that percentage hovers around 4 percent. Inglehart would likely agree with Jenkins on some of the reasons the latter puts forward for this momentous shift: the confluence of cultural and political factors that were part of Quebec’s “Quiet Revolution” seeking independence from Canada, higher levels of education, and the spread of new media. But too, there was a shift by which the state “took over many of the functions claimed by the church.” People were more prosperous and open to new ideas, and the Catholic Church now seemed backwards and irrelevant to most, particularly its pro-nativity norms.

Inglehart’s research found that the social norms of wealthier countries in general are starkly different from what they were in 1945. This is especially noticeable with regard to fertility rates, which “have moved from the high of the baby boom era to falling below the replacement level in most developed countries.” He has this to say about the changing social norms:

“The World Values Survey and the European Values Survey have monitored norms concerning sexual behavior and gender equality in successive waves of surveys from 1981 to 2020. Although deep-seated norms limiting women’s roles and stigmatizing homosexuality have persisted from biblical times to the present, these surveys now show rapid changes from one wave to the next in developed countries, with growing acceptance of gender equality and of gays and lesbians and a rapid decline of religiosity” (47).

The evolutionary nature of Inglehart’s theory also ventures into theology. He avers that among traditional hunter-gatherers around the world, it is rare to find a belief in a creator God, but rather the belief that “local spirits inhabit and animate trees, rivers and mountains” – in other words, animism. This is actually misleading, because among many indigenous populations, from North America to Africa to the Aborigines of Australia, the belief in a high creator god is quite common, but he tends to be distant and therefore people turn to intermediaries, from lesser deities, to spirits of various sorts, and to ancestors. But be that as it may, his point that agrarian societies, which are dependent on rain and sun for abundant crops, also prayed to god(s) for protection from plagues of locusts and disease, is more plausible. So is this paragraph leading into more widespread ethical norms today:

“Changing concepts of God have continued to evolve since biblical times, from a fierce tribal God who required human sacrifice and demanded genocide against outsiders, to a benevolent God whose laws applied to everyone. Prevailing moral norms have changed gradually throughout history, but in recent decades the pace of change has accelerated. The decline of xenophobia, sexism, and homophobia is part of a long-term trend away from tribal norms that excluded most of humanity, toward universal moral norms in which formerly excluded groups, such as foreigners, women, and gays, have human rights” (48).

I’m certain Jews, Christians and Muslims, particularly those on the conservative end of the spectrum, would want to push back against such a generalization. But it would be equally difficult to argue with the facts supported by such rigorous and comprehensive (both in terms of longitudinal and geographical) research. These World Values Surveys from 1981 to the present provide Inglehart with nine “hypotheses to be tested” – and having read the book, I believe they stand up rather nicely (pp. 51-2):

The interesting variance amidst the general trend

Inglehart presents a series of graphs seeking to map the evolution of various countries along two axes (see the latest version above). As you can see, the horizontal axis goes from “survival” to “self-expression,” or from the pro-nativity norms on the left to the individual-choice norms on the right. The vertical axis moves up from “traditional values” to “secular values” on top. This is similar to the impact of the Enlightenment on Christian Europe starting in the 18th century.

What is fascinating here is that countries, by and large, fall into regional or religious groupings. I mentioned “Protestant Europe” (Nordic countries plus The Netherlands and Switzerland) and how as a group they have served as trend-setters since the late 1980s to the present: their standard of living and their top scores on the World Happiness Report (see this year’s). This score is based on “comprehensive Gallup polling data from 149 countries for the past three years,” and takes into account six categories: “gross domestic product per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make your own life choices, generosity of the general population, and perceptions of internal and external corruption levels.” Generosity here includes acceptance of foreigners and minorities, but this might not last. Inglehart’s ninth chapter, “At What Point Does Even Sweden Get a Xenophobic Party?”, begins with a look at the political backlash caused by Angela Merkel who in 2015 opened the doors of Germany to almost a million refugees, most of whom being Syrian Muslims.

Another discernible cluster regroups the “English-speaking” countries of Britain, the US, New Zealand and Australia, and in the latest version of the map (2017-2020), they are just below “Protestant Europe” (not as far on the secular-rational values end), and the US is behind its counterparts in terms of self-expression values. What is striking also, is that the “Confucian” cluster (China, Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong) are around the middle of the map but on top (high secular-rational values), with Japan farthest along the self-expression axis. These nations, explains Inglehart, have in common a Confucian-infused culture which was mostly secular to begin with, so while they have become less religious, they have relatively always been so.

As you might guess, Muslim countries are by far the most religious. The World Values Survey has enough data over ten years for ten of them. They “show the highest absolute levels of religiosity of any major cultural group … But they are not becoming more religious” (85). Another factor setting them apart is that “age-linked differences are very small in Muslim-majority countries.” Younger people are only slightly less religious than their elders. This provides strong support for his hypothesis 7: “In societies where religion remains strong, little or no change in pro-fertility norms will take place.” But let me add that though the average birthrate in Muslim nations is the highest (2.9 per woman – replacement rate is 2.1), it is “down from 4.3 in 1990–1995.”

I would also inject that future polling and research will show that religiosity is waning in many Muslim countries. The example of Turkey for which we have research is not unique.

Finally, as “the publics of most ex-communist countries [now labeled “Orthodox Europe”]j showed steeply rising support for religion from 1981 to 2007 and (although this then slowed down) are still considerably more religious than they were in 1981.” In conformity with hypothesis 8 above, “a majority of the ex-communist publics show rising support for pro-fertility norms over the long term." Russia has been particularly vocal about stigmatizing gays, for instance.

What is the take-away?

This impressively researched and crafted book documents in granular detail the global shift in values over the last few decades. Inglehart’s analysis of the causes truly provides an illuminating explanation for what we witness today. But is it the last word on the matter? No book can claim this. Inglehart throughout acknowledges that there are other factors at play and he quotes other scholars on this. But his contention is that growing security, the erosion of pro-nativity religious norms, and the pull of individual-choice or self-expression values are the primary causes for the precipitous drop in religiosity in most countries since 2007.

Certainly in the US, he avers, factors contributing to secularization must also include the religious right’s “embrace of xenophobic authoritarian politicians,” the scandal of the Roman Catholic Church’s failure to deal with its child abuse problem, and for millennials and Gen-Z’ers, the failure of most religious establishments to recognize the validity of people’s choices in their acceptance or even adoption of other religions, their sexual orientation, their use of abortion, and drugs.

Nevertheless, I finished this book and said to myself, “well, the story of religion in America isn’t finished, and especially that of Christianity.” American history and the figures behind Christianity’s breathtaking growth in the 19th and 20th centuries tell us there is more to religion than this. One of the textbooks I use for my Comparative Religion course is Boston University’s Stephen Prothero’s God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Run the World – and Why Their Differences Matter. A New Times bestselling author, Prothero has nothing to prove religiously. After belonging for over a year to a Christian group as a college student (InterVarsity Christian Fellowship), he left Christianity and religion behind because his questions were not getting answered. So, as he puts in this interview, he made it his profession to keep asking those questions.

I love Prothero’s chapter on Christianity. He calls the 19th century “the Evangelical century.” Building on historian David Bebbington’s four marks of evangelicalism (biblicism, crucicentrism or centrality of the cross, conversionism, and social activism). He then explains:

“In the early nineteenth century these characteristics coalesced into a movement. Thanks to great revivals in England and the United States, and to the heroic missionary efforts of Methodist circuit riders and Baptist farmer-preachers, Anglo-America was rapidly missionized, and evangelicalism became the dominant religious impulse in the Protestant world …

In the nineteenth century, Christianity made a similar advance among English speakers, expanding even more rapidly than it had in the first Christian centuries. In 1800, less than one-quarter of the world’s population was Christian. By 1900, that figure had jumped to more than one third (34 percent). The most extraordinary growth came in North America, which saw the total number of Christians jump tenfold between 1815 and 1915. In the process, the portion of Christians among the overall U.S. population expanded from about 25 percent to about 40 percent. In Canada, the advance of Christianity was even more dramatic – from roughly one-fifth of the overall population to roughly one-half” (84-85).

Meanwhile, that evangelical missionary fervor produced an explosion of church growth in Africa. Prothero puts it this way, “There is no way that Christianity can keep up the growth it posted in Africa in the twentieth century – from 9 million souls in 1900 to 355 in 2000 – but thanks to a combination of that old-time revivalism and old-fashioned population growth, Africa and Latin America alike should bypass Europe by 2025 in terms of professing Christians” (96). He adds that the percentage of Christians in South Korea went from 1 percent to 41 percent in that same period.

Here from the Encyclopedia Britannica is a short summary of the great religious revivals in America in the 18th and 19th centuries. If I take off my religious studies scholar’s hat and speak like the Christian that I am, I say that this is more than just cultural and socio-historical dynamics at play. I believe this is God sovereignly stirring up these populations at that time and calling people to himself. It has happened again and again in many different places around the world. From the 1906 Azusa St. revival in Los Angeles, the Pentecostal movement fanned out and exploded. Today there are more than 600 million Pentecostals (who usually also identify as “evangelicals”) in the world. That’s why Prothero calls last century “the Pentecostal century.” Why then, and why here and not there? Only God knows. But this could happen again in 21st-century USA, and it is happening elsewhere as I write.

Religion’s Sudden Decline is a great read, and I recommend it heartily. I would just caution the reader that there is always more to the story. And for people of faith, there is more going on here than that which meets the eye of a social scientist.

In the first half of this post, the economist delegated by the US to last year’s G7 meeting in Cornwall, Felicia Wong, told us that she and her colleagues from the other 6 nations have noticed a shift in economic thinking. Call it the Washington Consensus of the 1980s giving way to the Cornwall Consensus. Neoliberalism with its mantra of free trade, privatization and deregulation (business interests first) was judged and found wanting. The coronavirus pandemic had exposed the futility of a model that led to obscene inequality and healthcare systems that were woefully inadequate for such emergencies, and the American one clearly more so than other advanced economies.

How do humans flourish? The international consensus on this question today is summarized in the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and as I tried to show, most of them cannot be reached without sustained, smartly targeted government investment. That is also what the “new economics” are saying. In order to achieve greater sustainable development on a global scale, we must prioritize common social goods above all. And they are all connected. Individual healthcare cannot be seen as detached from “environmental protections, affordable housing, living wages, and good public schools.” Science journalist Olivia Campbell quoted Sandro Galea, the dean of public health at Boston University, in her piece commenting on President Trump’s 2017 budget which called for reducing social welfare program funding by $272 billion:

“For the past 35 years, the U.S. has fallen further behind in health. This coincides with the Reagan policies of greater disinvestment in public good. We are now continuing along these lines — that’s what worries me.”

Trump’s healthcare policies followed the same reasoning that led to President Reagan’s drastic cuts to the programs initiated by President Johnson in the 1960s in order to create the “Great Society”: Medicare, Medicaid, substantial improvements to welfare, the National Endowment for the Arts, the national Endowment for the humanities, consumer protection measures, and a long list of environmental measures, including the Clean Air Act (1963), the Wilderness Act (1964), and the Endangered Species Act (1966).

How did Reagan’s far-reaching cuts to these social programs affect Americans, asks Campbell?

“A million children lost reduced-price school lunches, 600,000 people lost Medicaid, and a million lost food stamps. Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) could only serve a third of those eligible. WIC provides low-income pregnant women and children with formula and healthy food staples. Nearly 500,000 lost eligibility for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (a less-stringent precursor to TANF). This caused a two-percent increase in the total poverty rate, and the number of children in poverty rose nearly three percent.”