-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

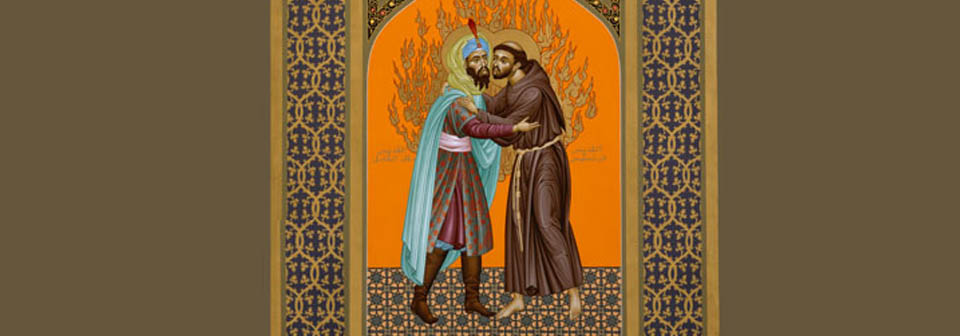

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

This review by Martin Awaana Wullobayi, a Ghanaian scholar who teaches and writes at The Pontifical Institute for Arabic and Islamic Studies (PISAI), was published in their journal in 2021: Islamochristiana 47. I take heart that an African scholar welcomes this work so enthusiastically. I hope with him that at a time when “hate speeches which divide and deprive humanity of all kinds of friendship and peace, the research topics discussed in Johnston’s book will be useful for reinforcing peaceful positive world view of coexistence between Muslims and Christians.”

[Over lunch in Washington in November 2021 I promised Mustafa Akyol that I would write a review of the book he wrote during the pandemic, which was published by the think tank where he works, the Cato Institute. I finally did write it, and it was published last month in the widely read Pakistani news outlet Global Village Space. As you will see, it dovetails nicely with what I am aiming for in my blog. I hope you will buy a copy of this excellent (and short) book. Read it and pass it around!]

I just finished reading Mustafa Akyol’s latest book, Why, As a Muslim, I Defend Liberty, for the second time, and that is when this peacebuilding component struck me. But first, as an Islamicist and Christian theologian, I deeply appreciate his articulate defense of individual human rights and his advocacy for a polity in which rulers are accountable to the people, who themselves are empowered to freely express their religious and political views, and thereby contribute to a diverse, rich and dynamic society where all contribute to the common good. He rightly calls this a “liberal” political order, which also includes “a system of free markets, limited governments, and charitable civil society” (117).

So first allow me to comment on his demonstration that Islamic theology and law, if rightly understood, lead to such a view, and then I want to show that the tone and tenure of his last two chapters make this an admirable work of peacebuilding between Muslims and a general Western public, whether secular people, Christians, Jews or people of other faiths.

Classical Islam and modern liberalism

It is significant that Akyol turns to 19th-century British philosopher John Stuart Mill for his definition of liberty. People should not be forced by the state or any other authority to adopt beliefs or behaviors against their own will. The only exception is when someone causes harm to others. That is because, along with other Enlightenment thinkers, Mill believed in the inherent dignity of the human person and therefore spoke of people’s “rights.” This Enlightenment conviction gave rise to the values enshrined in the American Declaration of Independence and its Constitution, for example. Civil rights and freedom of religion are central to the “classical liberalism” of European states, among many others, including the United States of America.

That is the point: this liberal order arose in Europe in the 18th century, but when we think of “classical Islam,” we are referring to the period during which Muslim theologians and jurists hammered out the central doctrines of their faith and established the main Sunni and Shi’i schools of jurisprudence – roughly between the third and sixth centuries of Islam (ninth to twelfth century CE). As Akyol points out, this is also at a time when Islamic imperial power was at its zenith. “Religious practice,” therefore, was fused “with state power” (36).

Though classical Islam was in some ways ahead of what we call “the West” today (most notably by establishing rules of war and securing at least some rights for minorities), it was still a child of the medieval period. The Qur’an banned coercion in religion (Q. 2:256), but state coercion was the norm everywhere, so that “the Christian Byzantines and the Zoroastrian Sassanids … all imposed their official religion, with laws that criminalized apostasy, often with the death penalty. That was also the norm in Islamic jurisprudence, but it’s a bit more complicated than that. The apostasy law is not found in the Qur’an.

Since the Qur’an has so little legal content, Muslim jurists turned to Prophet Muhammad’s example. Early on, his words and deeds had been passed down and transmitted orally, but already in the second century of Islam, as they were beginning to be transcribed, it was clear that some of these hadiths (short quotes of the Prophet and short stories of what he did) had been fabricated to bolster one faction over another in the many debates that had arisen. So, for example, in several of the recognized collections of the third century, one finds the hadith that stipulates the death penalty for anyone leaving Islam. To this day, this command stands in all five of the remaining schools of Islamic jurisprudence.

Medieval societies were not just oppressive; they were also patriarchal and openly demeaning for women. This is the main theme running through Akyol’s Chapter 2, “Why We Need to Rethink the Sharia.” The Quranic penalty for sex outside of marriage (zina) is 100 lashes (though you can find the death penalty in the Hadith). But one verse states that in order to be prosecuted, this crime has to be witnessed by four people. We know from its context that this verse was revealed to protect women from false accusations of zina, but the wording does not specify the person’s gender. Still, in some Muslim countries courts routinely use this verse to protect rapists and prosecute their victims. Traditional Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) consistently applied it to men, not women – a blatant injustice.

That is why most Muslim jurists today distinguish between Sharia and fiqh – that is, between the clear teachings of the Quran and the well-attested hadiths – which have divine authority – and the jurisprudence of Islam’s legal schools, which by definition has much human input and is, therefore, fallible. One area where this discrepancy shows is that fiqh confused crimes and sin. The Quran forbids a number of acts, like drinking wine, eating pork, gambling, lying, practicing usury, dressing immodestly, among others, but reserved punishment for these acts in the Hereafter. The Hadith, by contrast, assigned corporal punishment for those committing some of these sins – thereby turning them into crimes prosecuted by the state. Clearly the jurists’ fiqh was confusing two very different categories of acts that were kept separate in God’s Sharia. One reason for this confusion is the blending of religion with the state.

The authoritarian religious state

In the story of the Sultan who had just conquered Constantinople (now named Istanbul) in 1453 and who got so angry with his architect for building a mosque lower than the Hagia Sophia that he had his hands cut off, Akyol remarks that this only illustrates “the misery of the medieval world, where people’s precarious lives were at the arbitrary hands of capricious rulers” (42). Yet the story is not over. The architect sues the ruler, and the judge, upon hearing both sides in court, rules that the Sultan is guilty and must compensate the poor architect by paying ten silver coins a day out of his own salary for the rest of his life. Apocryphal or not, this story purports to show that God’s law is above all citizens, including their ruler.

Considering the authoritarian nature of so many Muslim-majority nations today, Akyol argues that the main takeaway from the Sharia, at least in its traditional interpretation, should be the rule of law, which must also include “the separation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches” of government. The reforms initiated by the New Ottomans in the 19th century were designed to do just this, but they knew that the Islamic jurists would not allow this, so they enacted a series of secular laws to sideline their opposition. Unfortunately, the constitutional regime of 1876 only lasted fourteen months. The new sultan, Abdulhamid II, suspended it and it wasn’t until 1909 that a “Second Constitutional Period” began, only to be scuttled by World War I.

Akyol rightly reasons that even though religion can easily become an instrument of political oppression (witness how religious rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran both excel in this domain), an emphasis on the Sharia’s intentions, or objectives, can turn religion into an instrument of liberation. Notably in Islamic Spain of the 14th century with the jurist Abu Ishaq al-Shatibi and running through the writings of the late Tunisian scholar Ibn Ashur, a minority tradition of Islamic legal theory has now become mainstream. The Sharia’s “overarching aim” is to promote human wellbeing by protecting five rights in particular: religion, life, property, intellect, and lineage. Ibn Ashur added liberty.

I had the privilege of translating from the Arabic original a twentieth century classic on this theme: the Tunisian politician Rached Ghannouchi’s The Public Freedoms of the Islamic State, mostly written while in prison in the 1980s (forthcoming, Yale University Press). Co-founder of the Islamist party Ennahda (or al-Nahda, “Renaissance”) and, until the current president’s coup in July 2021, speaker of Tunisia’s parliament, Ghannouchi uses these same arguments to demonstrate that a genuine “Islamic” government is one which is democratic by virtue of guaranteeing the separation of powers and the rotation of parties in power by means of free and fair elections. In fact, at the Tenth Congress of Ennahda in 2016 he was reelected president and said in his opening speech that Tunisia no longer needed an “Islamic” party. He also saluted Tunisia’s civil society “Quartet” that was awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize.

For Ghannouchi, therefore, Ennahda is no longer an Islamist party; rather, it’s a party among others, some of which are secular, but one that is intentionally imbued with Islamic values, the central one being liberty, or the fight against all forms of despotism. Though the nation that gave us the “Arab Spring” owes much to Ghannouchi’s consistent leadership, it still teeters on the edge of despotism at the moment. Nonetheless, Tunisia stands as a model of a nation that managed for a decade to balance religious and secular forces and seek freedom for all.

Akyol’s commendable peacebuilding skills

Mustafa Akyol wrote this book with three audiences in mind. First, of course, is his publisher and employer, the Cato Institute. Both the theme of liberty and the way he weaves it in and out of his chapters demonstrate his loyalty to the libertarian cause and the certain freedom he enjoys in marking it with his own stamp.

Plainly, his second audience is his Muslim correligionists – who, a billion and a half strong, display a wide spectrum of views and practices, to be sure. Akyol deploys some of the arguments he has made before, and most notably in his substantial work, Reopening Muslim Minds. Yet he offers new ones too, and especially new anecdotes and new sources along the way. By highlighting Islam’s achievements of the past – like the Prophet’s Medinan Constitution, laws to protect minorities, giant leaps forward in the arts and sciences by Muslims working together with Jews and Christians in ninth-century Baghdad and beyond, to name a few – he is able to draw his readers into discovering some of the reasons for the decline in later centuries, of which all Muslims are painfully aware.

Akyol’s third audience may be the most important to him: non-Muslims in the West and elsewhere. As we should all acknowledge, Islamophobia is the only prejudice that seems fair game in the American and European public square these days. Blame it on politics, if you will, it nevertheless has roots that go back long before – likely to the early Muslim conquests, then the Christian Crusades over two centuries, and more recently to the Islamic-inspired terrorism of the Middle East and Central Asia. A 2015 poll indicated that 61 percent of Americans had unfavorable views of Islam (much more than for any other faith) and a September 2021 article from the Pew Research Center revealed that “Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to say they believe that Islam encourages violence more than other religions.”

This is where Akyol’s peacebuilding efforts and skills shine through the most. Throughout the book his tone is balanced and honest, and nowhere more so than in his last two chapters. In Chapter 7, for instance (“Islam’s Lost Heritage of Economic Liberty”), he quotes extensively from two Western scholars who give the Islamic civilization credit for sowing the seeds of capitalism in the West. At one point he quotes Gene W. Heck in his 2006 book, Charlemagne, Muhammad, and the Arab Roots of Capitalism: “the Arab Muslims . . . provided much of the economic stimulus, as well as the multiplicity of commercial instruments that helped pull Europe up from the Dark Ages’ stifling grip” (104). He also shows that the central institution of medieval Islam, its religious endowments (waqf, pl. awqaf), because they were private fortunes untaxed by the state and so numerous that they financed untold charitable causes, “such as hospitals, soup kitchens, orphanages, mosques, schools, libraries, or monuments” (108).

By contrast, he has little admiration for “Islamic socialism” spearheaded by Egypt’s Gamal Abd Al-Nasser in the 1960s and “Islamic banks” that took off in the late 1980s, many of which turned into shameful pyramid schemes. The other shame, borrowing the words of Iraqi intellectual Ali Allawi, is that despite the presence of a “Muslim super wealthy class,” “There are no major research foundations, universities, hospitals or educational trusts that are funded by large charitable foundations. The scale and scope of the philanthropic work of the modern West – especially the US’s – is inconceivable amongst the Muslim rich” (118).

In my own experience, it is Akyol’s last chapter (“Is Liberty a Western Conspiracy?”) that is most effective in getting both sides to rethink their assumptions and hopefully begin to listen to each other. Why? This is because the suspicion of many Muslim conservatives that Western promotion of their liberal order is a tactic to better subjugate them allows him to make a historical incursion into 19th-century Western colonialism. And here Akyol does not mince his words. Napoleon, who in 1798 invaded Egypt, told its people that he had come to “rescue” them “from the hands of the oppressors” (123). Thirty years later, the French invaded Algeria inaugurating a 132-year rule, marked by "appalling—say, uncivilized—brutality" (122).

Yet many Muslims seem not to know that a whole cadre of Muslim intellectuals (“the first Muslim liberals”) weaponized these concepts of freedom and rights to fight for their independence. These liberals like the Egyptian Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti (d. 1822), Rifa’a al-Tahtawi (d. 1873), the New Ottoman thinker, Namik Kemal (d. 1888), and the Tunisian statesman Khayr al-Din (d. 1890) and the Indian Syed Ahmad Khan (d. 1898) – all of these raised the banner of freedom and human rights in the name of Islam and their national identity. Sadly, with the fall of the Ottoman Empire after WWI and the dissolution of the Islamic caliphate, the mood among Muslim leaders and thinkers turned to conspiracy theories. The American invasion of Iraq in 2003 “with no real justification” and the consistent support of Arab dictators has not helped the cause of freedom either.

Yet Akyol, ever desirous of speaking truth in a balanced way, immediately notes that Muslims cannot simply blame foreign powers for their authoritarian regimes. The responsibility lies with them in the end. Turkey in the 1990s, for example, was ruled by “authoritarian secularists” who “demonized the liberals [who were defending women demanding the right to wear a hijab to the university] as Western puppets, CIA agents, European Union mouthpieces, and payees of German foundations, which all supposedly had nefarious schemes against Turkey.” Meanwhile, “conservative Muslims respected those liberals, gave them a voice, and even began considering their views” (140). Fast forward to the 2010s, when these Muslim conservatives had been in power for a decade: “they also turned authoritarian – quite rapidly and unabashedly – and turned against these same liberals who were criticizing them. After all, they proclaimed, “liberals [are] the pawns of a heinous Western conspiracy against our embattled country – and its righteous, glorious, unquestionable leader” (140).

The same dynamic can be observed in Iran and elsewhere. Sadly, “liberalism” is the ideology of the enemy for many Muslims today. Yet liberalism is not a lifestyle, avers Akyol. It’s a “political philosophy” that defends both “freedom of religion” and “freedom from religion.” It is simply “a framework that allows different religions, metaphysical worldviews, or lifestyles to coexist, without oppressing each other, and follow their own ways, in peace and dignity, and free of the yoke of all kinds of thugs and tyrants” (143). Ghannouchi would agree, and in fact, this is the sentiment you can see expressed throughout my own blog.

In the end, Akyol – very adroitly, I would add – is using this book as a tool to bring many sides closer together – staunch Muslim conservatives and Muslim liberals; Muslims and their neighbors in Western nations; and even non-Muslim Americans who strongly disagree among themselves about how to evaluate the growing presence and influence of Muslims in their nation. I hope this book circulates widely. Truth-telling is so important to healing our divides. And balanced truth-telling, like it is here, has even more of a chance to be heard and acted on. This is peacebuilding at its best.

The Apostle Paul, a diaspora Jew from Tarsus (today’s Turkey), was also a Roman citizen. Perhaps that is partially why he writes to the church in Corinth, Greece, “Everyone must submit to governing authorities. For all authority comes from God, and those in positions of authority have been placed there by God” (Rom. 13:1). Jesus too, when faced with a loaded question about paying taxes to Rome (Jews in Palestine were under Roman occupation), famously answered, “Give to Caesar what belongs to Caesar, and to God what belongs to God” (Mark 12:17). The apostle John, now an old man and an exile on the Island of Patmos, identifies Rome as Babylon, the quintessential evil city, because it persecutes God’s people and it has “made all the nations of the world drink the wine of her passionate immorality” (Rev. 14:8 NLT).

So human government is at the same time 1) a necessary consequence of our human calling to manage God’s creation – all aspects, including fellow humans – justly and compassionately (Gen. 1; Psalm 8); and 2) a power structure that is easily subverted into becoming a cruel instrument of oppression. That second aspect is likely behind Paul’s exhortation to Timothy, his protégé:

“I urge you, first of all, to pray for all people. Ask God to help them; intercede on their behalf, and give thanks for them. 2 Pray this way for kings and all who are in authority so that we can live peaceful and quiet lives marked by godliness and dignity” (I Tim. 2:1-2, NLT).

Government must do its part

In this second half of my essay on Heather McGee’s book, The Sum of Us All, I will argue that the United States of America will never fulfill its founding pledge to provide liberty and justice for all unless its government redresses the longstanding injustices that have kept its poor from thriving, the most disadvantaged of whom are people of color. Heather McGee explains the role of government this way:

“A functioning society rests on a web of mutuality, a willingness among all involved to share enough with one another to accomplish what no one person can do alone . . . I can’t create my own electric grid, school system, internet, or healthcare system – and the most efficient way to ensure that those things are created and available to all on a fair and open basis is to fund and provide them publicly . . . For most of the twentieth century, leaders of both parties agreed on the wisdom of those investments, from Democratic president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-era jobs programs to Republican president Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System to Republican Richard Nixon’s Supplemental Security Income for the elderly and people with disabilities” (21).

Yet as we saw in the first half of this post, "For most of our history, the beneficiaries of America’s free public investments were whites only." A few examples:

Plainly, the net effect of all this government investment in its people under the New Deal was “to ensure a large, secure, and white middle class” (22). Yet with the advent of desegregation and the Civil Rights laws, white people faced the prospect of sharing those benefits with their Black co-citizens. With such a long history of privilege, white Americans had grown accustomed to these advantages, and so much so that ‘the elevated status’ these now conferred upon them seemed 'natural and almost innate.’” McGee explains,

“White society had repeatedly denied people of color economic benefits on the premise that they were inferior; those unequal benefits then reified the hierarchy, making whites actually economically superior. What would it mean to white people, both materially and psychologically, if the supposedly inferior people received the same treatment from the government? The period since integration has tested many whites’ commitment to the public, in ways big and small” (22-23).

One easy way to measure this white resentment is to follow the social science studies documenting the racist backlash in the wake of President Barack Obama’s election. Brown University political scientist Michael Tesler studied the connection between race and American attitudes toward the 2010 Affordable Care Act: “He concluded that whites with higher levels of racial resentment and more anti-Black stereotypes grew more opposed to healthcare reform after it became associated with President Obama” (52-53). Another study by Eric Knowles, Brian Lowery, and Rebecca Schaumberg at Stanford University found that the data “support the notions that racial prejudice is one factor driving opposition to Obama and his policies” (53). This is not surprising since people like Rush Limbaugh were calling the ACA “a civil rights bill … this is reparations, whatever you want to call it.”

Yet the people suffering the most from this resistance to the ACA were rural white people. McGhee points to the closure of 120 rural hospitals in the last ten years – and all of them in states that refused to expand Medicaid, as the ACA was calling for. The state leading in hospital closures is Texas (26 so far). At the beginning of the pandemic she talked to Don McBeath, who “does government relations for a Texas network of rural hospitals called TORCH” and asked him why the hospital system was in crisis mode. One big factor, he answered, is that “Texas has probably one of the narrowest Medicaid coverage programs in the country” (54). It turns out, a person making only $4,000 a year is still too rich to qualify for Medicaid! With so few people insured, it’s the state that has to pay all those unpaid medical bills. No wonder the system is failing and people are dying for lack of adequate care.

It’s the same story in other southern states like Georgia, Florida, Alabama and Mississippi. But that’s not how the Affordable Care Act was designed:

“When the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, it expanded qualification for Medicaid to 138 percent of the poverty level for all adults (about $30,000 for a family of three in 2020) and equalized eligibility rules across all states. But in 2012, a Supreme Court majority invoked states’ rights to strike down the Medicaid expansion and make it optional. Within the year, the lines were drawn in an all-too-familiar way: almost all the states of the former Confederacy refused to expand Medicaid, while most other states did. Without Medicaid expansion, people of color in those states struggle more – they are the ones most likely to be denied health benefits on the job – but white people are still the largest share of the 4.4 million working Americans who would have Medicaid if the law had been left intact. So, a states’ rights legal theory most often touted to defend segregation struck at the heart of the first Black president’s healthcare protections for working-class people of all races” (56).

The ironic fact is that Texas, with its majority of people of color (40% Latinx, 13% Black, 5% Asian) is represented by a state legislature with a two-thirds majority of whites and a three-quarters majority of males. Governor Greg Abbott intends to keep his GOP majority by means of crude voter suppression. In September 2021 he signed a bill with seven changes that make it harder for many to vote. And most of those will be people of color.

Voter suppression is also a theme McGee highlights in her book. Though it was a regular practice in southern states since the end of the Civil War, it wasn’t until the election of America’s first Black president that this movement, spearheaded and bankrolled by a group of right-wing billionaires, spread to all the swing states.

“These same billionaires funded the lawsuit, Shelby County v. Holder, to bring a challenge to the Voting Rights Act’s most powerful provision. Decided by a 5-4 majority at the beginning of President Obama’s second term, Shelby County v. Holder lifted the federal government’s protection from citizens and states and counties with long records of discriminatory voting procedures. Immediately across the country, Republican legislatures felt free to restrict voting rights … Between the 2013 Shelby decision and the 2018 election, twenty-three states raised new barriers to voting. Although about 11 percent of the population (disproportionately low-income people, seniors, and people of color) do not have access to photo IDs, by 2020, six states still demanded them in order for people to vote, and an additional twenty-six states made voting much easier if you had an ID” (149).

The Solidarity Dividend

Stanford economist Gavin Wright’s 2013 book, Sharing the Prize: The Economics of the Civil Rights Revolution in the American South, documents how “after the Voting Rights Act . . . southern . . . gubernatorial campaigns increasingly featured themes of economic development and education” (159). That is, they realized they couldn’t just get reelected via racist dog whistling. Increased numbers of ballots also meant that more poor folk had a chance to influence the powerful. This was a win for all the poor, Black and white, but it was mostly due to the Black leadership that all benefited from “investments in public infrastructure, including hospitals, roads, schools, and libraries that had been starved when one-party rule allowed only the southern aristocracy to set the rules” (159).

When democracy is unfettered and widened, allowing all citizens equal access to the polls and other means of political involvement, everyone wins. McGhee’s last chapter, “The Solidarity Dividend,” is the pièce de resistance, the whole point of the book. It begins with a long story of the transformation of Lewiston, Maine, from a booming and prosperous cotton mill city in the late 1800s to the dilapidated and economically depressed city it was until recently. It’s also the second largest city in a state “with the whitest and oldest population in the country,” one of the ten states ranking highest in opioid deaths. The governor, Paul LePage, “campaigned and governed on rhetoric about illegal immigrants on welfare and drug-dealing people of color” (255). He also “vetoed Medicaid expansion for the working class five times and delivered large tax cuts for the wealthy” (256). But that is not the end of the story, and certainly not for Lewiston.

McGhee spent several days walking the streets and talking to people, including the city’s deputy administrator and urban planner, Phil Nadeau, on the job there since the early 2000s. Manufacturing in Lewiston started losing in the 1970s, first to the American South where labor was cheaper, then in the 1980s to China and Southeast Asia. Young people were leaving with no one left to work the service jobs in town. As the population dwindled, Lewiston couldn’t attract new employers.

Then a miracle of sorts happened. In the early 1990s, the government gave a green light for thousands of Somali refugees to be resettled in the US. First, they were sent to the suburbs of Atlanta, Minneapolis, then to Portland, Maine, then to Lewiston. Many other African refugees came too – from Djibouti, Chad, Sudan and the Congo. With a sparkle in his eye, Nadeau told McGhee that these “new Mainers” were renting apartments that had long been empty and “filling storefronts on Lisbon Street that were vacant for a long time. They’re contributing to the economy” (258). Yes, it helped that there was “good regional planning and maintenance of the historic assets,” but a bipartisan think tank estimated that these recent African immigrants “contributed $194 million in state and local taxes in 2018” (259).

Phil Nadeau plans to retire soon and travel around the country to share his story “about how immigration can be a win-win for locals.” He was beaming, she writes. And just behind him, on the wall, was the portrait of a victorious Muhammad Ali looking down on Sonny Liston, whom he had just knocked out in Lewiston’s youth hockey rink in 1965. It was his career-defining fight. It was also when he made public his new Muslim name. Who would have guessed that so many Muslim immigrants would come to settle this city years later?

But Lewiston is far from alone in accepting refugees who then reverse the fortunes of the towns and cities that welcome them. McGhee notes, “for the past twenty years, Latinx, African, and Asian immigrants have been repopulating small towns across America” (259). The first place she mentions is 45 minutes from us, Kennett Square, PA. Arguably the mushroom capital of America, this sleepy town is now half Latinx, and these new immigrants have revitalized this traditional business (my wife’s grandfather co-owned a mushroom company in the vicinity).

This is happening across the country. One study of 2,600 rural towns since 1990 found that two-thirds of them lost population. But among those that gained population, “one in five owes the entirety of its growth to immigration” (260). By 2010, “people of color made up nearly 83 percent of the growth in rural population in America.” Though many of these longtime residents are surely tempted to feel threatened by the newcomers, “the growth and prosperity the new people bring give the lie to the zero-sum model.” As the local newspaper editor of Storm Lake, Iowa, wrote in 2018, if the local residents don’t put behind them their prejudice and work with the newly arrived to rebuild their hometowns, “there will be nobody left to turn out the lights by 2050. . . Asians and Africans and Latinos are our lifeline” (260).

But it’s not all about a growing economy. It’s also about new friendships budding and community being built. The first workers to come to Lewiston were French Canadians. One the stories that sticks with me (I did grow up in France), is that of Cécile Thornton (b. 1955) whose parents spoke French to her as a child. But like the second generation of many immigrants, she lost it over the years. While many others were offering ESL courses to help the immigrants learn English, Cécile, now retired and feeling alone because her whole family had migrated to other states, decided to visit the Franco Center downtown Lewiston to resurrect her French. But she only found a room full of elderly white people like herself who had given up trying to speak French.

But that visit was fruitful in another way. When she complained that she wasn’t going to learn any French there, one man told her, “You should go to the French Club at Hillview.” Hillview, she knew, was a “subsidized housing project.” Undeterred, she soon showed up at that French Club. To her shock, she was the only white person there. On that first visit, she hit it off with Edho who had recently come with his family from Congo. Greetings and small talk turned into the longest French conversation she had had since her childhood. She kept coming, and when she noticed that some of her new African friends were starting classes at the community college, she convinced them to attend the Franco Center, now a more convenient location for them. The result was a joy to behold: the two groups were now becoming friends – “the elderly white Mainers with halting vocabularies learning from new Black Mainers who spoke fluently” (262).

This life-changing experience gave Cécile a new lease on life. She now volunteers with asylum seekers, helping them navigate the social services and connecting them to other resources and people along the way.

Perhaps the most striking story is that of how Bruce Noddin and ZamZam became friends. Bruce, married with two kids, had owned a successful sports equipment store but then fell into drug and alcohol addiction and nearly lost everything, including his life. With his wife’s help and a good recovery program, he started to participate in a jail ministry. One day in the parking lot he met this lady who was bringing some hot food to the Muslim inmates to break their Ramadan fast. They started a conversation; she introduced herself as Zamzam and said he should “join the Maine People’s Alliance, a 32,000-member-strong grassroots group advocating for policies like Medicaid expansion, a minimum wage increase, paid sick leave, and support for home care” (263).

One thing led to another, and Bruce made a lot of new Muslim friends from Somalia and Djibouti. But he took initiative using his leadership skills, and he is today the main organizer of the yearly Community Unity Barbecue that draws hundreds of Lewiston residents. In speaking with McGhee, he expressed his deep gratitude for the turn his life had taken:

“The vision for me for this city, it’s [that we will] embrace our past, embrace our ethnicity . . . and then embrace the people that are here now that are just like those people who came here a hundred plus years ago. They’re exactly like that. But actually, they’re worse off. They didn’t always have a job. They were escaping atrocities in their country. They were escaping possibly dying or seeing their children die. And they need[ed] to work. There should be a massive amount of empathy from that next two, three, four generations down from those people that went through the same stuff as these people are going through, and saying, ‘We’re going to embrace you. You’re going to help us make this city great again’” (264).

McGhee then recounts how Ben Chin, the director of Maine People’s Alliance, helped to build a winning multiracial coalition which has begun to change the face of Maine politics. Ben, a millennial whose grandfather had emigrated from China and who himself had come to Lewiston for college and stayed, was also an Episcopalian lay minister. His community organizing over time paid off. Starting with the 2017 local elections, the Alliance won “a string of victories that begun to refill the pool of public services in Maine – and justify Ben’s faith.” McGhee explains: “Maine became the first state in the nation to expand Medicaid by ballot initiative over the governor’s repeated refusal” (269).

There was indeed a lot of race-baiting during that campaign, but Ben was adamant: what got them to the finish line was the multiracial coalition, “a broad-base of working-class people . . . not the muckety-mucks.” And for the first time, it was the immigrant-led political action committees that made the difference, including the “Somali taxi drivers who used their infrastructure of radios and vehicles to get elderly, homebound immigrant and poor Mainers to the polls safely” (269).

That is the “Solidarity Dividend,” she exclaims. The next year, these activists made possible the election of many new politicians who then “passed reforms to address the opioid epidemic and guarantee a generous paid-time-off for Maine workers.”

A transformational blueprint: TRHT

I want to end with a movement that was McGhee’s mother’s brain child (Dr. Gail Christopher). Her idea soon gained traction and in 2017 fourteen committees across the country adopted it as their project. The blueprint was called Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation (TRHT). By 2018, twenty-four universities had TRHT centers. Then came the George Floyd protests of 2020. In her words,

“Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA) introduced a resolution urging the establishment of a U.S. TRHT Commission. The TRHT framework was developed in 2016 with input of over 175 experts convened by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. The experts learned from the forty truth-and-reconciliation processes across the globe that had helped societies process traumas – from South Africa to Chile to Sri Lanka – but they explicitly left the word reconciliation out of the name for the U.S. effort. ‘To reconcile,’ notes the TRHT materials, ‘connotes restoration of friendly relations – “reuniting” or “bringing together again after conflict,” [whereas] the U.S. needs transformation. The nation was conceived . . . on this belief in racial hierarch’” (282).

In Dallas, it was Jerry Hawkins, a middle-aged Black man, who took up the TRHT challenge. At first, it was a stretch for him to even consider this, because a Black veteran had just killed five Dallas police officers and two civilians. But that too was why community leaders were urging Hawkins to take the job. Of the many suggestions offered in the TRHT manual, two of them immediately stuck out to him as urgent. Hawkins explains it to McGhee:

“One was a community racial history . . . this historical analysis of policy and place, of race, and the people from Indigenous times to present. And second was this community visioning process . . . this was of convening [a] multiracial, multifaceted group of people together, to come up with a shared community vision of how to end this hierarchy of human value?” (284)

Over three years, Hawkins and his committee dug deeply into the history of the Dallas area and interviewed hundreds of people from all walks of life. They published a report. As McGhee puts it, “In the opening pages, bold orange words bleed to the edges of a two-page spread: DALLAS IS ON STOLEN LAND. And a few pages later, again: DALLAS WAS BUILT WITH STOLEN LABOR.” She then adds, “Jerry called stolen land and stolen labor the first two public policies in Dallas” (284).

Whereas some cities in America boast multiple organizations working on racial equity, this is the only one in this conservative stronghold of Dallas. Yet it has brought about some spectacular breakthroughs in the hearts of many civic leaders already. Both the city and the Dallas school district boast offices of racial equity. Attitudes have begun to change.

Parting words

I began this second part of this essay on McGhee’s book by citing the Apostle Paul’s admonition to Timothy to “pray for all people,” and especially “for kings and all who are in authority.” Why? So that we could “live peaceful and quiet lives marked by godliness and dignity.” The TRHT manual is right. When it comes to racial healing in America, it’s transformation we need. People of faith would add the word “repentance.” Just as white leaders (and Black ones too) confessed their crimes under the Apartheid regime in South Africa, so healing and true peace could take root. In the U.S. today, we need many more local TRHT initiatives, and we need a national one as well. Join me in praying for that!

Then, perhaps, we could find bipartisan ways to pass laws to “fill the pool” and together – whites, blacks, browns, people of all faiths and no faith, or “the sum of us all” – rebuild the physical, social, and economic infrastructure this nation needs so desperately. Government, hand in hand with business and civil society (including churches, mosques, synagogues, etc.), could help build a society “marked by godliness and dignity,” a beloved community “with liberty and justice for all.”

The three Abrahamic traditions picture a Creator God who will judge individuals and nations with perfect justice. After all, He masters all the facts of each case, and He knows the secrets of every human heart. In my last post, I pointed out the positive achievements of J. William Fulbright in sending out thousands of young Americans to create goodwill around the world, as well as his racist attitude in supporting racial segregation at home.

We read in the Qur’an, “Whoever does good does it for himself and whoever does evil does it against himself: your Lord is never unjust to His creatures” (Q. 41:46). In other words, a good God has written justice into the fabric of His universe. In the vernacular, you reap what you sow. The original saying is in Paul’s letter to the Galatians:

7 Don’t be misled—you cannot mock the justice of God. You will always harvest what you plant. 8 Those who live only to satisfy their own sinful nature will harvest decay and death from that sinful nature. But those who live to please the Spirit will harvest everlasting life from the Spirit. 9 So let’s not get tired of doing what is good. At just the right time we will reap a harvest of blessing if we don’t give up. (Galatians 6:7-9, NLT)

Plainly, my country has a lot to atone for, from the near genocide of its native population to over three centuries of chattel slavery, from the Jim Crow laws and the terror of public lynchings to the red-lining and other laws designed to oppress and dispossess African Americans. But then came the civil rights era and more recently the thousands of whites flooding the streets in 2020 to protest racial injustice and call for an end to systemic racism. Repentance begins with taking stock of the evils we’ve committed. Then we decide to move in the opposite direction. I am hopeful we can change for the better … together.

This is the first of a two-part blog post on a book that came out this year, and none too soon. Heather McGhee, an African American woman (BA in American studies at Yale, JD from UC Berkeley) who has specialized in economic and social policy; additionally, she has “drafted legislation, testified before Congress, and contributed regularly to news shows including NBC’s Meet the Press.” She was president of Demos, a think tank focused on the issue of inequality and “now chairs the board of Color of Change, the nation’s largest online racial justice organization” (from the book jacket).

The book title is straightforward: The Sum of Us All: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. There are no numbered footnotes but a running documentation based on a few short phrases on each page found in the Notes section (100 pages in all!). This is followed up by two full pages of interviews, with full names followed by month and year, and so the book is peppered with the stories of the people McGhee met during her three years of traveling for this project. This is a page turner, but the research that went into it is colossal (because of her many connections, it was a collaborative venture from the start, with grants from several foundations).

A three-year USA road trip

Heather McGhee began her work at Demos in the early 2000s researching household debt. But she discovered it wasn’t just credit card debt that was ensnaring Black and Latinx families in greater proportion to white ones; by then too, disproportionately minority households were being saddled with bankruptcies and foreclosures because of a new type of mortgage loans ominously draining the equity from their homes. These became infamous during the Great Recession: subprime loans that were “sold to investment banks who bundled them and sold shares in them to investors, creating mortgage-backed securities” (92).

At first, it was only poorer communities of color who were canvassed for this type of “refinancing scheme” (first-time owners were in the minority). These investments soon became very profitable for Wall Street firms, while at the same time the loan sharks had no vested interest in helping the homeowners manage to repay them. As she puts it, “The homeowner’s loss could be the investor’s gain.” But because these arrangements worked so well for the financial firms, the mortgage people spread their “unfair and risky practices” to the wider market, and it was white households – in greater numbers – that now fell victim to this predatory lending.

Demos had launched an ambitious study in 2003 on household debt, the most comprehensive ever done on the topic. It garnered them “newspaper editorials, meetings with banks, congressional hearings, and legislation to limit credit card rates and fees” (xiii). But two years later, Congress passed a bankruptcy bill that favored the credit industry and hammered vulnerable household owners even more than before. McGhee took note: research will only go so far in Washington. So when years later Donald Trump entered the White House, she decided to do something radical: step down as president and spend three years touring the country to find out why what she had been taught about economics did not explain the data.

Yes, she was told, race and inequality are related, but in a linear fashion: “structural racism accelerates inequality for communities of color” (xii). But again and again, since the ascendancy of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, white Americans dependably voted for politicians who would shrink taxes for the wealthy while cutting back government spending on education, healthcare, and infrastructure – all goods their lives depended on. And now they voted in droves for “a man whose agenda promised to wreak economic, social, and environmental havoc on them along with everyone else” (xvii)! It didn’t make any sense.

Her first clue came from a series of psychology studies:

Psychologists Maureen Craig and Jennifer Richeson presented white Americans with news articles about people of color becoming the majority of the population by 2042. The study authors then asked their subjects ‘to indicate their agreement with the idea that increases in racial minorities’ status will reduce white Americans’ status.’ The people who agreed most strongly that demographic change threatened whites’ status were most susceptible to shift their policy views because of it, even on ‘race-neutral policies’ like raising the minimum wage and expanding healthcare – even drilling in the Arctic. The authors concluded that ‘making the changing national racial demographics salient led white Americans (regardless of political affiliation) to endorse conservative policy positions more strongly’” (xviii).

She then realized that this idea of racial groups in competition with one another, and whites in particular feeling threatened by the progress non-whites could potentially make, was exactly the propaganda they had been fed over the last few decades by conservative media: beware, because there are “makers and takers,” “taxpayers and freeloaders,” and the liberals lavish “handouts” on those too lazy to work, be they people of color or immigrants forcing their way in. But this racism is a self-defeating trap for the whites just as much as everyone else. This zero-sum paradigm is really a lie peddled by the wealthy one percent who know that fanning the flames of racism gives them the cover they need to exploit the masses – “hoping to keep people with much in common from making common cause with one another” (xxii).

An idea rooted in our history

That zero-sum idea goes all the way back to our history of chattel slavery. The story of the United States cannot be told “without the central character of race” (7). Racial taxonomies of the 17th century aimed not just at differentiating various groups of humans, but at assigning relative worth to each of them. The resulting hierarchy – with Europeans on top – gave the master race “moral permission to exploit and enslave.” [A 2019 article in Quaternary Science Reviews argues that the death of 56 million indigenous people in the Americas after the arrival of the Europeans resulted in the increase of carbon in the atmosphere!] From the beginning, the US economy was built “on literally taking land and labor from racialized others to enrich white colonizers and slaveholders.” The corollary only reinforced the status quo: “that liberation or justice for people of color would necessarily require taking something away from white people” (7).

Slavery enriched both South and North. Slaveowners benefited from both free land and free labor. Think about it:

Under slavery’s formative capitalist logic, an enslaved man or woman was both a worker and an appreciating asset. Recounts economic historian Caitlin Rosenthal, “Thomas Jefferson described the appreciation of slaves as a ‘silent profit’ of between 5 and 10 percent annually, and he advised friends to invest accordingly” (8).

The ongoing costs incurred by the slaveowner were minimal, and he even had an incentive to use sexual violence to increase the number of his slaves. But the benefit accrued to Northerners as well. Northern insurance companies (including some still in business today, like New York Life and Aetna) profited from policies that insured the life of slaves. Such life insurance policies would pay back owners three quarters of a slave’s market value upon death. The fortunes of many other northern corporations were tied up with slavery, which “legally persisted in the North until 1846.” Slavery was feeding all parts of the US economy.

Another way race drilled the zero-sum mentality into the white psyche was in the way it defined who was an American and who was not. Most of the Europeans emigrating to the colonies in the early period were poor and certainly not “free” – overwhelmingly, they came from the servant class. But after several mixed racial rebellions in the late 1600s, colonial governments began to enact new laws that reveal “a deliberate effort to legislate a new hierarchy between poor whites and the ‘basically uncivil, unchristian, and above all, unwhite Native and African laborers’” (10). Here, the zero-sum reality begins to sink in: only whites are given the right to own property and slaves lost that right. One law even stipulated that the proceeds from the sale of a slave’s property would be given to “the poor of the parish,” who were, of course, white.

Hence, at the dawn of the eighteenth century, whites could experience a form of freedom they never dreamed of having in the old country – but it came at the cost of Black subjugation. As McGhee puts it,

“Eternal slavery provided a new caste that even the poorest white-skinned person could hover above and define himself against. . . . You can imagine how, whether or not you owned slaves yourself, you might willingly buy into a zero-sum model to gain the sense of freedom that rises with the subordination of others” (11).

Racism drained the pool

That is the title of McGhee’s second chapter. The public swimming pool is a prime example of white Americans choosing to deny themselves a public good they’re were very much enjoying, but the fact that Black Americans were using it was enough of a reason to shut it down and fill it with concrete. From the late 1940s on, this happened all over America. Sometimes, rather than share the municipal pool with African American children, city councils leased the pool for a song to a private, whites-only association, as happened in Warren, Ohio, and Montgomery, West Virginia. Montgomery, Alabama, had a sprawling public park with a zoo, community center, and the largest pool of the area, as well as a dozen other parks in the city. But when a federal court ruled that monopolizing it for whites was unconstitutional, the city council dissolved the entire park system. That was the rule almost everywhere.

“Draining the pool” is an apt, if sad, metaphor for the way American racism drained public spending for a variety of public goods over the next decades. That it hurt more whites than people of color did not seem to factor into white voting patterns. This is what she learned all over the country from talking to people of all walks of life over three years: anti-government animus was tied to that zero-sum worldview that equates progress for people of color with loss of status and wealth for whites (by the way, Black respondents never saw it that way).

What has that done for us as a nation? Though we are the wealthiest nation on earth, our per capita government spending “is near the bottom of the list of industrial countries, below Latvia and Estonia.” She explains, “Our roads, bridges, and water systems get a D+ from the American Society of Civil Engineers. With the exception of about forty years from the New Deal to the 1970s, the United States has had a weaker commitment to public goods, and to the public good, than every country that possess anywhere near our wealth” (17). We’ve been “draining our pool” for a good while now.

Historians and other social scientists have pinpointed exactly when white voters pulled their support for an activist government – one that, according to 65 percent of white people in 1956, “ought to guarantee a job to anyone who wanted one and to provide a minimum standard of living in the country.” Yet between 1960 when that figure was up to 70 percent and 1964 when it crashed to 35 percent, something momentous must have happened. And it did.

“In August 1963, white Americans tuned in to the March on Washington (which was for ‘Jobs and Freedom’). They saw the nation’s capital overtaken by a group of mostly Black activists demanding not just an end to discrimination, but some of the same economic ideas that had been overwhelmingly popular with whites: a jobs guarantee for all workers and a higher minimum wage” (29).

Race was clearly an issue, but not that old form of “biological racism” that put Europeans at the apex of a hierarchy of human racial groupings. No, white Americans had adapted to at least some of the narrative of the civil rights era. Instead of biological racism, it was “a new form of racial disdain” based “on perceived culture and behavior.” As professors Donald R. Kinder and Lynn Saunders’ 1996 book demonstrated (Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals, U. of Chicago Press), this new kind of anti-Black animus was more of a “racial resentment.” Their study of the American National Election Studies (ANES) survey data indicated that though whites seemed more comfortable with racial equality and integration, “their backing for policies designed to bring equality and integration about has scarcely increased at all. Indeed in some cases white support has actually declined” (30).

McGhee and a colleague dove into the 2016 ANES data and discovered that “there was a sixty-point difference in support of increased government spending based on whether you were a white person with high versus low racial resentment. Government, it turned out, had become a highly racialized character in the white story of our country” (30). She explains,

“When the people with power in a society see a portion of the populace as inferior and underserving, their definition of ‘the public’ becomes conditional. It’s often unconscious, but their perception of the Other as underserving is so important to their perception of themselves as deserving that they’ll tear apart the web that supports everyone, including them. Public goods, in other words, are only for the public we perceive to be good” (30).

This attitude, however, does not come out of thin air. McGhee shares how a 2014 book by one of her law school professors, Ian Haney López (Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class), helped her “connect the dots.” President Reagan followed his advisors’ advice by continuing “the fifty-state Southern Strategy that could focus on taxes and spending while still hitting the emotional notes of white resentment.” She then quotes him in a conversation they had about this:

“Plutocrats use dog-whistle politics to appeal to whites with a basic formula. First, fear people of color. Then, hate the government (which coddles people of color). Finally, trust the market and the 1 percent.”

Apparently, this strategy has worked very well, at least until 2020, and this discourse is not about to disappear, funded as it is by a coterie of conservative billionaires and millionaires. But it has “drained the pool” for all of us, as McGhee demonstrates throughout her book – in education (think of student debt, for instance), healthcare, the gutting of unions and workers’ rights, housing, infrastructure and environmental protection.

God’s judgment and grace

I started with the thought of dark clouds of judgment about to close in on us as a nation. The Hebrew Bible’s prophets certainly point to God’s swift judgment on nations that oppress others. Yes, he raised up Babylon, and before that, Assyria, to bring judgment upon several nations, including Israel. But they too in the end harvested destruction for the crimes against humanity they committed so wantonly.

Heather McGhee is not a religious person, she tells us. Nor was her mother, though their family included Christian and Muslim members. But she suspects that there is a transcendent being or force that somehow lies behind reality. But as you will see in the second part of this post, she is certainly hopeful. You don’t see anger or resentment as she tells the story of how racism has cursed our nation to this day. She is amazingly optimistic that a large enough interracial coalition can gather and turn this nation around.

I hope she’s right. As people of faith, as most of my readers are, I surmise, we pray that God himself will step in, lead us to repentance (I include myself, as this article makes clear), and then find ways to work together for the common good across all barriers of race, cultures of origin, and class.

We can’t escape it. We are people of our time and place. This often makes for spectacular blind spots in our worldview. For example, how can you be at the same time a politician like J. William Fulbright with an expansive vision for international cooperation after World War II and then oppose a Supreme Court decision to integrate schools in 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) and then fight civil rights legislation tooth and nail in the 1960s?

I read an article in Foreign Affairs the other day by Charles King, Georgetown University Professor of International Affairs and Government. His title: “The Fulbright Paradox: Race and the Road to a New American Internationalism.” [I’ll be quoting from the article in the Foreign Affairs July/August 2021 issue, pp. 92-106]. I instantly agreed with him that this topic is timely. In his words,

“Fulbright’s ideas were shaped at a time of party polarization and chin-jutting demagoguery unmatched until the rise of Donald Trump. His life is therefore an object lesson about global-mindedness in an age of political rancor and distrust – but not exactly in the ways one might think” (93).

The paradox in question, or Fulbright’s blind spot, I will argue, has been dramatically exposed for a majority of white Americans today following the unprecedented protests for racial justice after the murder of George Floyd by a white policeman in May 2020. Most of us now recognize that racism in this country is baked into many of our institutions and laws – hence the expression, “systemic racism.”

J. William Fulbright’s globalist vision

The senator from Arkansas (1945-1974) who has served the longest as chair of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations was no doubt one of the great American globalists of the 20th century. A great admirer of President Woodrow Wilson, he managed to found the greatest academic scholarship and exchange program, which Congress named after him. Since its inception in 1946, the Fulbright Program sponsored by the U.S. Department of State has awarded a variety of grants to more than 400,000 academics from over 160 countries of the world. Every year, about 3,000 American students and scholars travel the world to do research and build greater trust and understanding all over the globe. Their motto is “Connecting People. Connecting Nations.”

In fact, Fulbright was a born leader with a lofty vision. Graduating from the George Washington Law School in 1934, he worked as an attorney in the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department. He then left Washington to teach law at his Alma Matter, the University of Arkansas. After just three years (1939), he was appointed president of the university. To this day, he was the youngest university president at 34. Yet from the start, his vision was global. As World War II broke out in Europe, he publicly declared that the U.S. should enter the war alongside the Allied forces. He was now feeling a pull to enter politics.

Fulbright was elected in 1942 as a Democratic representative, becoming a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. He quickly became an outspoken freshman lawmaker. In particular, he drafted a resolution in 1943 that passed the House (Fulbright Resolution), which called for greater involvement in peacekeeping efforts overseas and strongly urged the U.S. to join the United Nations.

It didn’t hurt either that Fulbright had been a Rhodes scholar, meaning that he was granted that prestigious scholarship to pursue graduate studies at Oxford University. That must have been a factor in his endeavor, soon after his election to the Senate in 1944, to establish what has become by far the most important American academic exchange program.

But almost from the beginning, his globalist vision and this program in particular, put him in the crosshairs of another Senate powerhouse: Senator Joseph McCarthy who in the early 1950s had devoted his career to expose and punish any Americans of influence who were deemed to have communist sympathies. He had chaired the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations for that purpose and “had upended lives and destroyed careers.” Charles King picks up the narrative at this point:

“By January 1954 . . . the committee was up for reauthorization. When senators’ names were called to approve a motion to keep it going, only one nay came from the floor: that of the junior Democratic senator from Arkansas, J. William Fulbright. ‘I realized that there was just no limit to what he’d say and insinuate,’ Fulbright later said of McCarthy. ‘As the hearings proceeded, it suddenly occurred to me that this fellow would do anything to deceive you to get his way.’ Within a year, Fulbright had helped persuade 66 other senators to join him in censuring McCarthy and ending his demagogic run. By the spring of 1957, McCarthy was gone for good, dead of hepatitis exacerbated by drink” (92).

McCarthy, as you might have guessed, was categorically opposed to the Fulbright program. He believed that those “scholarship recipients were America-haters who promoted communism.” Fulbright once dryly responded to his objection in a hearing, “You can put together a number of zeros and still not arrive at the figure one” (93).

In the 1960s, Fulbright took aim at the Vietnam war and “he convened a series of Senate hearings that interrogated the war’s origins, its cost in lives and prestige, and pathways to ending it. The televised hearings, which ran intermittently from 1966 to 1971, brought high-level debate about the conflict into American living rooms.” King figures that these hearings were instrumental in changing middle America’s mind on the war. President Johnson tried to persuade one TV network to play I Love Lucy reruns instead of these live debates. Within a month of hearings Johnson’s “approval ratings on the war slid from 63 percent to 49 percent.” He was right to be concerned. One 27-year-old John Kerry, for instance, came representing Vietnam Veterans Against the War and posed a question that stunned the nation, “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”

Fulbright’s influence on this issue was heightened by his initial position of support for the war in 1964, but with Nixon in the White House in 1969, Fulbright had become “an antiwar activist.” I love this commentary by King on the constitutional role of Congress in limiting the powers of the presidency:

“The counterculture had the streets, but Fulbright had the Constitution’s requirement that the Senate hold the presidency to account, even when both institutions were controlled by the same party. It was an enactment of the founders’ vision that has never since been equaled” (96).

God’s justice and the nations

In his concluding paragraph, King writes that “Fulbright’s biography is evidence that the best of what the United States produced in the last century was inseparable from the worst – a complicated, grownup fact that ought to inform how Americans approach everything from education in international affairs to foreign-policy making” (106). And that “best” has to do with what several generations of people worldwide have experienced through the Fulbright scholarships, grants, and cultural outreach. His main point in writing this article is to argue that Fulbright, like his globalist peers, had a huge and ugly blind spot – racism; but he also founded an institution that put bright and eager Americans in touch with young leaders in many other countries, breaking down barriers and stereotypes and creating a momentum toward further constructive partnerships. But notice: this was shouldered by the U.S. government. So his final point is this:

“And to generations of people in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas, Fulbright’s most enduring contribution is something that the United States now has an opportunity to bring back home: the astonishing, liberating idea that governments have a duty to help their people lose their fear of difference” (106).

That phrase “lose their fear of difference” is the very tip of a gigantic iceberg of human attitudes and behavior. We humans construct our identity from being part of a family, a tribe, a religious or political grouping, and even a nation – and all of this often in opposition to “the other,” in all of these categories and more. But it’s not just about highlighting difference and thereby polishing our own brand. It’s about power too. Minorities and weaker groups have historically suffered from exploitation, oppression – even to the point of genocide in many cases – at the hands of groups in power.

Allow me to interject some thoughts from the Hebrew prophets here. Their unanimous message is that God rules over the nations and will judge each one justly. One of the criteria for that judgment is how the weak, the poor and oppressed are treated, either within their own borders or how they treat other nations they conquer. For example, one of the four “Servant Songs” of Isaiah (songs attributed to the future Messiah) puts it this way:

“Look at my servant, whom I strengthen.

He is my chosen one, who pleases me.

I have put my Spirit upon him.

He will bring justice to the nations.

2 He will not shout

or raise his voice in public.

3 He will not crush the weakest reed

or put out a flickering candle.

He will bring justice to all who have been wronged.

4 He will not falter or lose heart

until justice prevails throughout the earth.

Even distant lands beyond the sea will wait for his instruction” (Isaiah 42).

In Ezekiel, where I have been reading lately, we find a number of prophecies addressed to various nations. Several of the smaller neighbors of Israel (like Ammon, Philistia, Moab, and Edom, or the descendants of Jacob’s twin brother Esau) will be wiped out and disappear because of their “bitter revenge and long-standing contempt” for the people of Israel (Ezechiel 25). Others like the wealthy coastal city state of Tyre on the Mediterranean will be destroyed by the Babylonians, because of its arrogance, greed, and exploitation of lesser powers (chapters 26-28). Egypt promised to help the Kingdom of Judah (the last remnant of Israelite rule) when Babylon came to crush it, but in fact didn’t lift a finger. Its land will become desolate as a result, many will be killed and others will be scattered to many lands. But, unlike most of the others, God promises to restore its fortunes in the near future; however, with this warning: “It will be the lowliest of nations, never again great enough to rise above its neighbors” (Ez. 29:15; four chapters are nevertheless devoted to God’s messages to Egypt).

Fulbright, a man of his times and place (the South)

I am reading Charles King’s essay on Fulbright in light of the Hebrew prophets. Yes, he was indeed “a man of his times and his place,” as I will explain. But his views on race, especially in light of the millions of white Americans marching in our streets with their black and brown compatriots in 2020 to call for an end to systemic racism, shine a light on “America’s Original Sin,” as I explained in early 2019. The prophets’ mission was to deliver God’s message to the people and those messages were predominantly negative. God was exposing their sins so that they would repent and thereby avoid the harsh judgment against them, ominously looming on the horizon.

The parallels with “critical race theory” (CRT), this movement started in legal studies in the 1970s but mostly spearheaded by human rights activists, are obvious. As within any other movement, there is a healthy diversity of views and I certainly would not endorse all of them. But the basic intuition and direction of research in this growing subdiscipline is exactly what the Hebrew prophets would say in our day: to lay bare the assumptions of white supremacy that have guided this nation from the start and the strategies that were put in place along the way to bolster a system that favored the power of white Americans and sidelined the descendants of the slaves whose forced labor by all accounts multiplied this country’s wealth and established its power. White supremacy and the 15th-century Doctrine of Discovery (see this piece about how churches are taking a stand against this) also gave rise to the idea of Manifest Destiny which was simply a justification for the ruthless dispossession, oppression, and killing of millions of Native Americans.

Even one of the central concepts of CRT, intersectionality, can be discerned within those prophetic texts. This is the concept that the rich oppressing the poor is not just about attitudes of prejudice, greed, and pride in the hearts of the rich. It is also about how justice is trampled in the courts and how laws can often be drawn up so as to increase the power and wealth of the elites at the expense of the poor. In other words, racism and exploitation of the lower classes can easily be woven into a society’s institutions and laws. Intersectionality also means that the weakest members of society all suffer from the abusive power of the dominant group – women, people of color, and the lower classes in general.

As John Dawson, the New Zealand missionary in Watts, Los Angeles, wrote in his 1994 book, Healing America’s Wounds, unless the American church (and society as a whole, I would add) openly recognizes, repents of, laments, and makes amends for the heinous crimes committed against the African slaves and the Native American peoples and their descendants (including the Jim Crow laws, the redlining of cities, and the myriad other ways the Indian nations were driven off their lands, their children put into boarding schools “to kill the Indian” in them, etc.), the nation as a whole will continue to be broken, at war with itself. This includes the dozens of new laws in Republican-majority states to disenfranchise voters of color.

As you read Dawson's book, you begin to feel that there’s an eerie “disturbance in the force,” in Star Wars parlance. Past sins of injustice fester like a cancer in the body politic, in society at large, and inhibit healing and true thriving as a nation. Ezekiel reminds us that God will also judge the United States. More likely, he has been judging it all along, but he longs for its people – starting with its leaders, including in the church – to confess and lament these sins publicly and make restoration. Then there will be healing.

That’s why I see God’s Spirit in 2020 using that tragic series of police killings of black men and women as a tipping point to send crowds of mostly white people into the streets. In God’s providence, it was a revelation for many of us white Americans. We were listening to our compatriots of color and were beginning to take in many of the injuries done to them, almost on a daily basis, and the fact that many of these indignities stem from disparities that often begin at birth in poor neighborhoods high in crime, and continue with decrepit schools and a reduced chance to go to college and succeed. We also began to shudder at “the talk” black parents have to have with their children about how to deal with the police, and especially when they begin to drive.

But we must not stop here. The Spirit is calling us to take up the hard work of facing the racism, the injustice and the rampant inequality, and fix it in the very structures of society. Consider joining a movement like the one cosponsored by the Rev. William J. Barber II, which builds directly on the Poor People’s Campaign launched by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. shortly before his assassination in 1968.

Now back to Fulbright. Charles King shows that U.S. foreign policy should not be “narrated” from New England but rather from the American South. As many historians have shown, the great wealth that came from such commodities as cotton and tobacco – both produced by slaves – ensured that southern politicians in Washington were great advocates for free trade, which requires broad international alliances and a stable world order. But the motive was not about promoting mutual respect among nations. Senator Jefferson Davis, who had been slated to become the first president of the Confederate South, had this to say about relations with Latin American countries. Spreading democracy was nowhere in his thinking, as we see in this 1858 speech:

“Among our neighbors of Central and South America we see the Caucasian mingled with the Indian and the African. They have the forms of free government, because they have copied them. To its benefits they have not attained, because that standard of civilization is above their race” (98).

King shows that these racist ideas spread after the Civil War:

“The South didn’t so much lose the Civil War as outsource it, spreading new theories and techniques of segregation beyond the region itself. Domestically, the Jim Crow system cemented the legal, economic, and political power of whites, as did the brutal counterinsurgencies against Native Americans fought by the regular military on the western plains. Places that had no association with the old Confederacy, from Indiana to California, rushed to create their own versions of apartheid, including prohibitions on interracial marriage and restrictions on voting” (99-100).

Historians have also brough to light the kind of values that motivated and undergirded American military interventions in Cuba, Hawaii, Haiti and the Philippines: “manliness, white supremacy, and faith in one’s own noble intent, even when other people experienced it as terror.” American policy, whether at home or overseas, was, in the words of diplomat and political scientist Paul Reinsch in his 1900 textbook World Politics at the End of the Nineteenth Century: “a harsh and cruel struggle for existence . . . between superior races and the stubborn aborigines” (100). This worldview makes the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII seem quite natural. As war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote from the Pacific theater at the time, “In Europe we felt that our enemies, horrible and deadly as they were, were still people. But out here I soon gathered that the Japanese were looked upon as something subhuman and repulsive, the way some people feel about cockroaches and mice” (100).

It was against this backdrop that the great black scholar and civil rights leader W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in the American Journal of Sociology in 1944:

“The power of the southerners arises from the suppression of the Negro and poor-white vote, which gives the rotten borough of Mississippi four times the political power of Massachussetts and enables the South through the rule of seniority to pack the committees of Congress and to dominate it” (100).

But after WWII it was the reality of decolonialism that gained the ascendancy, and the courageous stand taken by African Americans against race-based segregation and dispossession was making world headlines. This wasn’t lost on the Soviet Union. In an amicus brief to the Supreme Court by the U.S. Justice Department on the occasion of the Brown v. Board of Education case, we read that “Racial discrimination furnishes grist for the Communist propaganda mills and it raises doubts even among friendly nations as to the intensity of our devotion to the democratic faith” (101). The cat is out of the bag, as it were, and American leaders knew that a tarnished reputation was a huge handicap in the ideological battles of the Cold War. The same can be said today with regard to ascending world power China. But as mentioned above, today's extreme political polarization is also a welcome opportunity for Russia, Iran, and others to use the internet to divide us even more.

Parting words

Charles King has a personal connection to Fulbright: he grew up in the Ozarks of Arkansas on a property adjacent to that of the Fulbright family. He graduated from the University of Arkansas, studied at Oxford, was a Fulbright scholar, and lived for many years in Washington. But the two men are from different eras. King's latest book (2019) was a New York Times bestseller: Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century. He knows that when it comes to these issues of equity and social justice, he stands on the shoulders of many who went before him, starting with many Black and women scholars.