-

-

Bethlehem, city of Jesus' birth, of churches and mosques

-

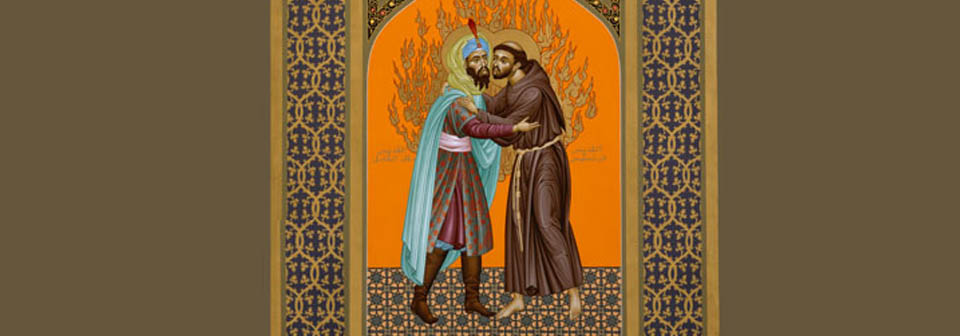

St. Francis of Assisi embraces Malik-al-Kamil, the sultan of Egypt, as an early example of Muslim-Christian dialog

-

This is my 2018 review of Ayman S. Ibrahim's The Stated Motivations for the Early Islamic Expansion (622-641): A Critical Revision of Muslims' Traditional Portrayal of the Arab Raids and Conquests (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., 2018).

Amazingly, the goal of halving the number of undernourished people worldwide was just about reached hrough the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs, 2000-2015). UN chief Ban Ki-moon declared at the end of that process, “The MDGs helped to lift more than one billion people out of extreme poverty, to make inroads against hunger, to enable more girls to attend school than ever before and to protect our planet.” Still, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) says 815 million people (10.7% of the total 7.6 billion) suffer from chronic undernourishment.

Quoting from the best recent studies, CBS reported on May 2018 that one in eight adults in the United States suffered from food insecurity (“not having enough food because of a lack of money or other resources”) and one in six children. Other research shows one in seven adults and one in five children. The ten most food-insecure states are all in the south.

My goal in this blog post is mostly to highlight the work of one faith-based organization, Bread for the World. I will also introduce the successor program to the MDGs, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, 2015-2030), which seek to provide states and NGOs alike a common blueprint for improving the lives of those most struggling in today’s world.

The functional side of our world community

Arguably, our world is riven with conflicts under the surface, with some already boiling over in several parts of the world. Syria and Yemen, for different reasons, are magnets drawing in many powers that could easily end up fighting one another in the process. North Korea still threatens to use its nuclear weapons, and the Trump administration seems poised to attack Iran.

At the same time, the story behind the MDGs is an inspiring tale of nations coming together, crafting a new vocabulary and agreeing on a new strategy to fight the scourge of poverty and injustices done to women and other marginalized groups. It inspired struggling nations to roll up their sleeves and work on those goals in a way that made the most sense to them.

After the UN final MDG report came out in September 2015, Bread for the World was full of praise for the success of this mammoth collective project:

“According to the final report, the MDGs spurred "the most successful anti-poverty movement in history.” In fact, the goal of lowering the global rate of people living in extreme poverty (living on less than $1.25 a day) by half was more than met. Extreme poverty fell from 47 percent in 1990 to 14 percent by 2015, an even more impressive achievement when you consider that the world's population continued to grow in the meantime.”

Naturally, much work lies ahead, but this success spurred the global community to set a new batch of goals for the next 15 years. There were eight broad MDG goals: “eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; achieve universal primary education; promote gender equality and empower women; reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; ensure environmental sustainability; and forge global partnerships among different countries and actors to achieve development goals.”

In the next round the eight goals became seventeen goals and sustainability became the overarching principle undergirding them. A New York Times article on the same day gave more details regarding these SDGs:

“The new global goals are more ambitious, and are meant to apply to every country, not just the developing world. Stated in broad terms, the goals are accompanied by 169 specific targets meant to advance the goals in concrete ways. Most are meant to be achieved by 2030, though some have shorter deadlines.”

Three of the goals, for instance, target environmental sustainability:

13. Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

14. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources.

15. Sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, halt biodiversity loss.

I’ll leave it at that for now, but in a coming post I will return to the SDGs as a projection of a philosophical and interfaith perspective I believe is crucial for all of us to ponder and adopt in one form or another.

Ending food insecurity in the US

The hunger goal for the MDGs was to cut the number of food deprived people in half, and as mentioned above that goal was just about reached. But hunger was subsumed under “poverty.” The Sustainable Development Goals, by contrast, are much more ambitious (because they now seem attainable!):

1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.

How “ending hunger” in the developing world is much wider topic than I can deal with here, but doing so in the United States, the most powerful and wealthy nation on earth, should not be that difficult. Plainly, it is a national disgrace that so many children and adults do not have access to sufficient food. Yet, on the flip side, says the 2018 Bread Hunger Report, the solution is simple: make sure that “everyone who wants a job can get one and that it pays a sufficient wage.” That “decent job” is one that “should provide families with the means to put food on the table. For those who are raising children, a decent job should allow them to balance their responsibilities as an employee and parent.”

But there’s a wider context as well: decent jobs are the number one factor for combatting hunger in developing nations. So here is the main thesis of this 2018 hunger report:

“The zero-sum narrative holds that prosperity in another part of the world must come at the expense of workers in the United States. But it doesn't have to be this way. Better policies can make the difference. We can reclaim the American Dream for all in our country, and we can share that powerful dream with our neighbors who are striving for more than a subsistence life.”

Before moving on to the text itself, let me emphasize one more time: this Christian organization’s research and political advocacy is built around a central principle: it must all be done in bipartisan fashion. More than ever in our present political climate, this is so vitally important!

The report lays out four points, which I will summarize here:

1. Stagnant wages are contributing to hunger. Since 1980, when adjusted for inflation salaries have gone down for lower class and lower middle-class families. Economic growth has in a spectacular way benefitted the top one percent of Americans who earn at least one million dollars a year (have a look at their Figure 1). That said, what has allowed the lowest earning Americans to barely keep their heads above water has come through such federal nutrition programs as SNAP (known previously as food stamps), Woman, Infants, and Children Program (WIC), and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). These are “indispensable,” says the report. What is more, if economic growth had been more equitable, “it could have raised income for everyone.”

Then comes this important statement about human dignity and work. “Labor is more than a commodity. The work people do is a source of dignity in their lives, or at least that is how it should be. It is dehumanizing when wages are not sufficient to provide for basic living costs.” When rent, transportation, childcare, and health care have been paid for, then people buy food. Put otherwise, “Food is the most flexible item in a household budget, which is why hunger is usually episodic. It shows up after fixed costs are paid—when monthly SNAP benefits are exhausted but the next paycheck has not yet arrived.”

2. Policies can improve opportunities for low- and modest-income workers. On the one hand, we count on markets to “function efficiently.” On the other, they cannot do so unless government enacts and monitors rules that allow it to do so. Another necessary government job is to ensure that workers are protected and adequately supported. Yet it has fallen behind in making sure workers earn a living wage: “The federal minimum wage, currently set at $7.25 an hour, has not been raised since 2009. When adjusted for inflation, it is worth 27 percent less today than it was 50 years ago.”

Besides raising the minimum wage, government has to set up an adequate infrastructure, particularly in areas where poverty is concentrated. That includes better public transportation, better roads, but also better “human infrastructure,” like better schools, “child nutrition and child care.” Those “are cost-effective investments in the current and future workforce.”

Prison reform figures high on the list of things to fix in this area. Close to one third of non-working men between 25 and 54 are behind bars. Because most of them are fathers, they represent the population most exposed to poverty and hunger. Yet thousands of statutes nationwide bar individuals with criminal records from working. Members in Congress on both sides of the aisle would like to see that change. That could mean shorter sentences and more effective prison programs preparing inmates to re-enter civilian life. More, “A nationwide infrastructure initiative could be a new source of jobs for these returning citizens.” [Clearly too, racism and poverty are closely related in the US; Bread has a helpful report on that].

Surely the people most vulnerable to poverty and hunger are undocumented immigrants, even though their rates of employment and entrepreneurship are higher than the national average. The quicker we enact immigration reform, the faster we will empower a population that will energize and expand our economic output. And, of course, we would then be obeying the biblical mandate to care for the “foreigners living among you” (Leviticus 19:34, Deuteronomy 16:11; 26:11; Ezekiel 47:22; Malachi 3:5).

3. Reducing poverty in developing countries can contribute to economic opportunity for all Americans. This is not a zero-sum game. To the contrary, as poverty rates have fallen around the world, trade has increased on all sides and all have gained – sadly, not always equitably, but the potential for fairer trade is palpable, if we push for it. Think of it this way: in 1985, 29 percent of US exports went to developing countries; today, it’s about half, and that could rise.

“Compared to other high-income countries, the United States invests a much lower share of national income in helping displaced workers adapt to the changing global economy. The United States also invests less in the health, education, and economic security of its people.” We could learn a lot from other developed countries in this area.

4. Through advocacy and political engagement, citizens have the power to bring about change. The report chronicles the constant rise of economic inequality, the erosion of people’s faith in the democratic system, and particularly as they witness the outsized role of corporate money in politics. The 2017 tax cut law only exacerbated the yawning gap between the haves and the have-nots.

The Bread report reminds us that we citizens in a democratic polity have a say in how government establishes the rules that frame our collective life as a nation. We need to take more responsibility by means of a) legislative advocacy (“telling our members of Congress what we want them to do on specific issues”); and b) elections advocacy (“getting in on the ground floor”). This is what this organization has been doing for 44 years: “organizing churches and Christians to urge Congress to take actions that are important to hungry people.” It then adds, “In its early years, Bread for the World played important roles in establishing the WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) nutrition program and child survival programs around the world.”

Put simply, soup kitchens and food pantries are necessary, but nowhere sufficient to fight hunger in the US. Congress must pass laws to keep the programs that have proven effective in the past and level the economic playing field so that no one is left behind. And we can help make sure our members of Congress do the right thing.

Interfaith advocacy is the most effective

On a website sponsored by the Islamic Circle of America you can read an excellent article on this topic, “Interfaith Action on Hunger: A Shared Obligation.” Though people of all faiths have worked together to eradicate hunger before, it is especially the effort of Jews, Muslims and Christians that is the easiest to marshal. Their texts plainly mandate caring for the needy, and especially feeding the hungry. At one point the author writes,

“Around the world, Muslims, Christians, Jews, Hindus, and others are hard at work, working together to eliminate hunger. Individual Muslims and other can support these efforts in any number of ways, as interfaith action is valuable in a wide range of initiatives that target hunger, from local soup kitchens and food banks to programs that invest in international food security or engage in global advocacy.”

Finally, on the occasion of Pope Francis’ visit to the US in September 2015, a group of 69 diverse American religious leaders issued an “Interfaith Religious Leaders’ Pledge (downloadable in a window in Bread’s 2018 Hunger Report). Of that number three were Jewish and three were Muslim (including the CEO of Islamic Relief, Anwar Khan). This pledge coincided with the UN’s signing of the SDGs, but the Pope who had spoken on this topic at the UN also spoke about this to a joint session of the US Congress. So I will end with the American religious leaders’ pledge, and in particular the next to last paragraph which highlights the role, not only of civil society and NGOs, but also of the American government:

“Ending hunger will require action by all sectors of society and by all the nations of the world. Yet a shift in U.S. national priorities seems crucial to ending hunger in our country and internationally. People of goodwill can disagree about policy strategies. But ending hunger by 2030 seems unlikely unless we can achieve a shift in U.S. national priorities by 2017, so that our government helps to put our nation and the world on track toward ending hunger."

May it be so! And may we citizens, from all political parties, strongly urge our elected officials to work toward that goal. Ending hunger by 2030 is achievable.

As my writings attest, I believe strongly in countering today’s rampant Islamophobia (and not just in the “West”). At the same time, I believe that interfaith dialog entails a mutual commitment to finding truth. This includes, at the right time and place, discussions about difficult and tense topics.

No topic is more fraught with fear and rancor than that of Islam and terrorism. I dealt with that last year, showing that the issue was vastly overblown and callously exploited for political purposes (see part 1 and Part 2). But part of the reason it raises such potent emotions is that it is tied to a centuries-old Christian and Jewish complaint, namely the early military expansion of the Prophet Muhammad’s rule in Medina.

This issue of the early Muslim conquests is a particularly vexed one. On the one hand, a good eighty percent of evangelicals (the Christian tribe with which I mostly identify) subscribe to the right-wing mantra that Islam is a religion of hatred and war. Franklin Graham may bear the most responsibility for that, since he declared shortly after 9/11 that “Islam is a very wicked and evil religion.” Sadly, his father, Billy Graham, who was likely the most influential evangelical in the twentieth century, would never have said or believed such a thing (read here religion scholar Stephen Prothero’s piece about how he believes Franklin is dismantling his father’s legacy).

On the other hand, I have to disagree with the standard Muslim apologetic which claims that the early Muslim conquests were a) defensive military operations; and b) all about spreading the blessings of the new faith these leaders had received. That said, I do agree with them that the oft repeated statement, “Islam was spread by the sword,” is also very misleading. But before explaining what I mean, let me first start with some remarks about biographies of the Prophet Muhammad.

Kecia Ali’s The Lives of Muhammad

Boston University’s Kecia Ali is best known for her work on Islamic feminism and the Islamic legal literature on women (see for instance Sexual Ethics and Islam, exp. & rev. ed., 2016). Yet in 2014 she had a book published on modern bibliographies of Muhammad (The Lives of the Prophet, Harvard U. Press). Her main thesis is that the Muslim and non-Muslim biographies, in spite of and perhaps because of their disagreements, have been mutually interdependent. My concern here is to look at the issue of war, but first, a quick summary of her main points.

Ali is building on another recent work that spans the last twelve centuries of biographical writing (Tarif Khalidi, Images of Muhammad, Doubleday, 2009). Keep in mind that Muhammad, “alternatively revered and reviled, has been the subject of hundreds if not thousands of biographies since his death in the seventh century” (Ali, 2). Khalidi sees three distinct stages:

1. From the late 8th through the early 10th centuries, we have the “Sira [biography] of primitive devotion,” which as we will see in the next section contains even “stories or anecdotes that may offend the sensibilities of Muslims” (19).

2. From the 10th to the mid 19th century Muslims composed various forms of literature, most of it devotional, which pruned the early material for theological consistency with an emphasis on “Muhammad’s superhuman qualities – his pre-eternity, miraculous powers, and sinlessness … [and] an object of love and devotion” (20).

3. The final stage began at the end of the nineteenth century: “the polemical Sira, written largely to defend Muhammad’s reputation against the attacks of the European Orientalists” (20). This is the stage on which Kecia Ali focuses her Lives of Muhammad.

Medieval Christian writings about Muhammad in one way or another magnified his perceived lust for power and women, and his excessive recourse to violence and war. In a paper I presented to a 2015 conference on Islamophobia at Temple University, you can read about the long history of anti-Muslim polemics in the United States since the seventeenth century.

What is interesting here is that according to Khalidi “two British Lives of the nineteenth century ‘haunt’ modern Muslim biographers” (46). The first is Thomas Carlyle’s 1840 lecture, “The Hero as Prophet.” With clear romantic overtones, Carlyle argues that Muhammad (he used the French “Mahomet”) is “a true prophet” when British imperialism was fast approaching its zenith. Following the German writer Goethe, he spoke of Muhammad’s natural genius and the sincerity of his thinking and actions, which demonstrated his perfect integration into the world of his time. Yet the lecture was less about Muhammad and more about good and true men in general. To Ralph Waldo Emerson he explained that his lecture proved that “man was still alive, Nature not dead or like to die; that all true men continue true to this hour” (49). Not surprisingly, Muslims have quoted from this lecture again and again, to this day.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, William Muir’s The Life of Mohamet from Original Sources was written as an aid to the Christian missionary enterprise, representing in Khalidi’s words, the “Missionary-Orientalist complex.” A British civil servant who rose through the colonial administration during his four decades in India, Muir was an evangelical who earnestly wanted to see Hindus and Muslims come to faith in Jesus. He was also a very capable Arabist and scholar, and so he embarked on this ambitious biography of the Muslim Prophet. Fifty years later (1905), his obituary proclaimed it as “the standard presentment, in English, of the Prophet of Islam.” As Khalidi sees it, Muir’s use of the original sources was imbued with “deadly accuracy” and that’s why his biography “was found so distasteful by Muslim readership” (51). Interestingly, Ali wants to tweak that statement: “though he was faithful to his sources, he presented information gleaned from them in unflattering ways.”

That is the crux of the matter. In the next and last section, I will try to show that the earliest sources as a whole constitute an “unflattering” portrayal of Muhammad’s raids and expeditions.

Ayman S. Ibrahim’s The Stated Motivations for the Early Islamic Expansion (622-641)

This is how I began my review of this book for a Southern Baptist journal (its full title includes: A Critical Revision of Muslims’ Traditional Portrayal of the Arab Raids and Conquests; Peter Lang, 2018). I still haven’t heard from the editor and this part might be cut out, but it’s certainly relevant here:

“I cannot claim total impartiality in reviewing this important book. When it was still in dissertation form, I was Ibrahim’s outside reader. I was impressed with his stellar historical skills, encouraged him to keep working on it for publication, and we have become good friends in the process. In fact, it was he who, countless times, helped me with Arabic passages I struggled with in a long translation project for Yale University Press.”

Ibrahim, born into an Egyptian evangelical family, is now Associate Professor of Islamic Studies at Southern Seminary (Louisville, KY) and Director of the Jenkins Center for the Understanding of Islam. Ayman would be the first to agree with me that our friendship has included some strong disagreements at times, particularly about specific pieces he has published in The Washington Post, Religion News Services, and elsewhere. It is fair to say that we have learned from each other. But I have no reservations about this book, as my second paragraph indicates:

“Even aside the significant research he is now doing for his second PhD (on conversion in early Islam) at the University of Haifa, Ayman Ibrahim is fast becoming a noted historian in early Islam. This book, The Stated Motivations, demonstrates his wide and strong grasp of the sources and critical issues relative to early Islamic history and historiography. Part of the great input of his mentor J. Dudley Woodberry in his PhD program was to put him in contact with three exceptional historians of Islam, Chase Robinson, Gabriel Said Reynolds and David Cook. No doubt they in turn generously invested in Ibrahim because they saw his obvious gifting and hard work.”

Rice University historian of Islam David Cook writes in his recommendation of this work: “No recent scholar comes close to matching his total command of Arabic sources, both past and present. The issues he raises concern not only distant history, but contemporary Arab interaction with that history. Ibrahim proves conclusively that – contrary to contemporary apologetic-historical analysis – the initial conquests were not religious in nature, nor were they for the sake of self-defense.” Needless to say, I believe this is a very significant contribution to Muslim-Christian conversations today. It is a delicate one, and perhaps too sensitive at the moment, but a very necessary one in the long run.

[I will post my review in Resources when it is actually published later in September and since I have no room here to review the book properly here, you can check back later if you are interested in more details (the book costs $100).]

Ibrahim deals with the current state of historical research on early Islam, and particularly on the issue of the reliability of the written texts, the earliest of which date to almost two hundred years after Muhammad’s death. Just from that standpoint his book is a great primer on mainly four types of literature Muslims produced that touch on some aspect of the early expansion of Islam: a) the abundant maghazi literature (military campaigns); b) the sira literature (most famous of which is Ibn Hisham’s, d. 838), though the two genres overlap a great deal; c) the futuh literature (conquests made by Muhammad’s successors); d) early Muslim histories (tarikh), which begin in the late ninth century, the most famous being the work of al-Tabari (d. 923). His sources beyond that cover the whole medieval period up to today.

In concluding his Chapter 3 on Muhammad’s maghazi, Ibrahim writes, “a careful study of our Arabic sources allows that political domination and economic gain were chief motivations for the early expeditions” (99). There are no indications that these campaigns were defensive or for spreading Islam through conversions. Indirectly, of course, strategic planning to defeat Mecca by force of arms, diplomacy, and gaining dominion over most of the Peninsula allows the Prophet to set up a rule in which Muslims are in control. But even that kind of motivation is not spelled out in the texts. We also know that by the end of the Umayyad period (the dynasty ruling in Damascus, so in the 740s) only about ten percent of that vast population from Spain through North Africa, and all the way to the Indus River on the edge of India were actually Muslims. So no, in that sense Islam was not “spread by the sword.” Part of the reason was the initial prejudice against non-Arabs. Another part was that converts no longer paid the poll tax, thus creating a loss of revenue. Then too, Islam as a "religion" was not yet developed in the first generations after Muhammad. The full ethical implications of the new faith had not yet been drawn out.

I’ll take just one example – the Battle of Badr (624), the first great Muslim victory over Mecca. There is no indication in the sources that the Meccans had attacked the Muslims first or that the Muslims had intended to preach their message in order to convert them. Rather, in a speech to his soldiers Muhammad “spoke of the abundance of possessions and properties, which awaited the Muslims upon victory” (74), and that many of the elite leadership were present in that caravan. Ibrahim makes five other points from his reading of the sources:

1. The Meccans, though vastly outnumbering the Medinans, tried very hard to avoid a confrontation, likely because they wanted “to secure their trade and social status.” The Meccan leader Abu Sufyan changed his route to avoid the Muslims and sent for reinforcement. Meanwhile, one of their wealthy notables, Ataba ibn Rabi’a was negotiating with his colleagues for a Meccan peace treaty with Muhammad, which would include also some financial compensation. The news of the Meccans’ unwillingness to fight reached Muhammad and the Believers, but it only added to their determination to attack and defeat the Meccans. As it turned out, Ataba was killed even before the battle started.

2. The later Muslim historians used “supernatural elements and deliberate exaggerations to add a spiritual nature to its course of events.” The aim was to show that this victory was due to God’s supernatural intervention. Though details vary widely among writers, Ibn Hisham describes for example “heavenly angels riding in the midst of sky clouds, wearing colorful ama’im (turbans) and beheading the non-Muslim Meccans” (76).

4. The vast discrepancies in the retelling of the battle might indicate that the writers were more interested on communicating their own particular slant on the events than in “documenting what actually happened.” For example, some texts report that Muhammad was leading the battle in front; others that he was protected by an elite guard; others that he was fighting for himself in the middle. One report even says that he was afraid the Medinan “helpers” (ansar) were going to abandon him.

5. The sources seem to point to revenge as the main Muslim motivation. They had been driven out of Mecca and their properties confiscated. Now they were going to get even with them. One report states that the blood of the Meccans reached the armpit of Ali. Others point to a strategy of killing the most influential leaders. Even the Prophet “instructed the killing of two major leaders of the Quraysh after they had surrendered and being held as prisoners of war” (78, emphasis his). Also, some Meccans were spared because of their clan affiliations. It’s hard not to conclude that this was mostly a tribal war.

6. Finally, the disputes over the spoils after the battle were ferocious, so much so that Muhammad had all the spoils brought to him and he distributed them once they had returned to Medina.

There is so much left unsaid here, but allow me to end with some remarks I made at the end of my last chapter in Earth, Empire and Sacred Text. I had referenced Indian Muslim journalist M. J. Akbar’s 2002 book, In the Shade of Swords: Jihad and the Conflict between Islam and Christianity (Routledge). In this book Akbar argues that Muslims are called to defend the faith, by the sword if necessary. He makes a direct connection between this early expansion of Islam, the promise to the martyrs in battle that they will be rewarded in the next life, and the current spate of jihadi fervor in Muslim lands.

Akbar’s book was not a scholarly work, though as a journalist he did some serious research. My point in mentioning his book was to shine a light on this early military expansion of Islam. I’m an outsider, I reminded the reader, and as such I could only venture two suggestions to my Muslim friends. First, take seriously the modern and postmodern hermeneutical turn when reading the Qur’an. Somehow those passages calling to fight had not only a particular historical context (which most Muslim scholars today recognize) but also perhaps stand in need of reinterpretation in an interdependent, globalized world. Then I wrote the following:

“Second, in the spirit of Islamic theology, I am pleading with my Muslim brothers and sisters to reconsider the ethical implications of the early Muslim conquests. Just as I have forthrightly condemned the Crusades and Western colonialism as contrary to the spirit and letter of the gospel, I would urge some soul-searching on the Muslim side” (517).

Enough said here. I hope the conversation will continue, God willing. And I know that that is His desire. In the meantime, we will continue to work together for greater peace and prosperity for all in our troubled world.

I was asked in 2011 to contribute an article to a special issue of the journal Religions published by the Doha International Center for Interfaith Dialogue (Qatar). The Editor-in-Chief is Patrick Laude, a faculty member of the Georgetown University extension in Doha and this was a special issue on "Ecological Responsibility." The Keynote article was written by Prince Charles of Wales and my article was the first one after his. Twelve more followed mine, including one by Omid Safi, "Qur'an and Nature: Cosmos as Divine Manifestation in Qur'an and Islamic Spirituality." Two other articles were written by Christians, both Orthodox. There were two Jews, three Muslims (including Safi), one Buddhist, one Hindu, one Chinese author emphasizing the diversity of views of China's "Three Teachings" (Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism). There was also one article on indigenous African religions and environmentalism and another by Yale scholar Mary Evelyn Tucker on "World Religions, Earth Charter and Ethics for a Sustainable Future."

My article, “Muslim-Christian Trusteeship of the Earth: What Jesus Can Contribute,” is a combination of things I have written before, except for my extensive use of Glen Stassen and David Gushee's Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003). I was also arguing that being trustees of the Earth included peacebuilding among humans. Truly, a holistic approach to caring for the enviroment also entails we take care of one another as fellow human beings. Peacebuilding encompasses all the above concerns, as Glen Stassen's ten steps for Just Peacemaking demonstrate. Wars have become more and more destructive on people and nature.

Take notice of their interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount, especially. I believe you will find the idea of "transformative initiative" very helpful, whatever your spiritual orientation.

I was finally able to finish the revised draft of my translation of Ghanouchi’s book in June and in July I completed the changes to my book, Justice and Love: A Muslim-Christian Conversation. The Equinox Publishing owner and chief editor told me she was delighted I got this done after an almost three-year hiatus and would work on getting an outside reviewer immediately. This doesn’t mean there won’t be more work for both of these projects, and especially for the translation – I will have to deal with comments and suggestions coming from Ghannouchi’s family and two blind reviewers this fall! But I feel a great sense of relief!

Justice and Love is five chapters and is a bit more than 150 pages. All five chapters and the Conclusion begin with short case studies of conflicts or injustices that cry out for resolution in contexts where Muslims and Christians are involved: Israel-Palestine, Pakistan, Egypt, racial reconciliation in the US, and Nigeria. Three of those I did from scratch last month and that’s why I checked out an edited book by Susan Thislethwaite, Interfaith Just Peacemaking (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). I did not use it in the end, but I will now. It is so very significant for the sake of advancing the cause of peace in our troubled world.

In addition, I know several of the contributors to this book, including the man who conceived of this project from the beginning, the late Glen Stassen (d. 2014), a Christian ethicist and activist who finished his teaching career at Fuller Seminary in Pasadena, CA. Have a look at his obituary in the NY Times: “Glen Stassen, Theologian; Championed Nuclear Disarmament.” The first paragraph is telling:

“Glen H. Stassen, a Southern Baptist theologian who helped define the social-justice wing of the evangelical movement in the 1980s and played a role in advancing nuclear disarmament talks toward the end of the Cold War, died on April 25 in Pasadena, Calif. He was 78.”

Stassen’s seminal work was Just Peacemaking: Transforming Initiatives of Justice and Peace (Westminster Press, 1992). His main insight was to add a third option between pacifism and just war theory, namely preventing war in the first place. How is that possible? Stassen listed ten practical steps to achieve conflict resolution and the prevention of war. But already a movement was forming around these ideas. For one thing, twenty-three scholars collaborated with him over five years in refining this paradigm. The third edition of that edited book was published in 2008 (Just Peacemaking: The New Paradigm for the Ethics of War and Peace, Pilgrim Press). Interestingly, President Barack Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech mentioned each one of these of these ten steps for a just peace.

[For a more in-depth treatment of how the teaching of Jesus led Glen Stassen to his work on just peacemaking, see my article on Jesus, environmentalism and peacebuilding in the journal Religions published by the Doha International Center for Interfaith Dialogue.]

These scholars represented several disciplines, many Protestant denominations, and a number were Catholic as well. Right from the beginning, they phrased these practices in a way that could be adopted by adherents of other faiths. Meanwhile, shortly after 9/11, the Justice Department under President George W. Bush gave a substantial grant to Fuller Seminary for a Muslim-Christian dialog project in partnership with the Salaam Institute for Peace and Justice in Washington, DC, from 2003 to 2008. I personally benefitted from that grant in two ways. I received grant money for my writing of Earth, Empire and Sacred Text, and I participated in two long weekend conferences in Pasadena with Christian and Muslim scholars (2005, 2006). The result was Peace-Building by, between, and beyond Muslims and Evangelical Christians, Mohammed Abu-Nimer and David Augsburger, eds. (Rowman & Littlefield, 2009). Glen Stassen, as you might imagine, was very much a part of those dialogs.

The story of the present book, Interfaith Just Peacemaking, picks up precisely at this point. The positive momentum generated by those Muslim-Christian dialogs led to a new, wider project, and this time with the support of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Jewish scholars were invited to join and in total thirty scholars gathered in January 2009 for the Interfaith Just Peacemaking conference. They decided to put together a book with introduction and conclusion, ten chapters, with three scholars from each tradition contributing to each chapter.

Thistlethwaite notes that the Jews and Muslims drew attention to the importance of scripture: “We are text-based faiths; we need to base our peacemaking practices on our scriptures” (3). But another important issue was building trust. How do you create an atmosphere in which no one feels under attack and therefore has to write defensively, or apologetically? This would apply especially to the Muslim scholars, considering the growing Islamophobia in the 2000s. Fortunately, during the earlier conference at Stony Point (2007) participants had to present papers that included past instances when their own scriptures had been used to justify violence. Naturally, the fact that all three traditions had plenty of examples to share served as an icebreaker. “So we experienced a remarkably nondefensive spirit as we worked together” (3).

By now I’m sure you’re wondering what those ten practices of just peacemaking are …

The ten practices to build peace

Practice Norm 1: Support nonviolent direct action

Think of Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr, but also of Christian and Muslim women who came together to protest the civil war under the name Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace. Because they staged a sit-in outside the presidential palace while negotiations were ongoing, they pressured the mostly male assembly to sign a peace agreement in 2003)

Practice Norm 2: Take independent initiatives to reduce threat

These are a series of steps taken graciously by one side, and clearly communicated, in order to de-escalate tensions and encourage reciprocation. Under presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy the US said it would halt nuclear testing for a year and if the USSR also halted, it would continue to do so for another year. In both cases the Soviet Union reciprocated and eventually this led to “the treaty that halted nuclear testing above ground, under water, and in outer space” (34).

Practice Norm 3: Use cooperative conflict resolution

Former adversaries are encouraged to actively and creatively cooperate in finding mutually acceptable solutions. “To truly engage in this kind of initiative, participants must be willing to listen carefully, understand the perspectives of their adversaries, and suspend judgment, even though they may personally disagree” (51). Though the Sri Lankan government defeated the separatist movement (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) in 2009, the end of the 26-year civil war left plenty of tensions between Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims and Christians. The USIP partnered with the Columbo-based Centre for Peace-Building and Reconciliation and began training 100 clergy and professionals from all four communities. This has made a remarkable difference on the ground in the last decade.

Practice Norm 4: Acknowledge responsibility for conflict and injustice and seek repentance and forgiveness

This is an attempt to build empathy and trust between both sides. This is a lot more promising than it seems, mostly because the idea of apology, pardon and reconciliation has gained so much traction in literature, sociology, political science, and psychology. Yet even as it has garnered interest in these secular contexts, interfaith movements have been multiplying in many parts of the world, and not least in Israel-Palestine, the Balkans and in West Africa.

Practice Norm 5: Advance democracy, human rights, and interdependence

I will end with a few more thoughts on this one. Just one word here: “no democracy with human rights fought a war against another democracy with human rights in all the twentieth century (although some funded and fomented wars by others)” (87).

Practice Norm 6: Foster just and sustainable economic development

This involves not just material prosperity but also “the cultivation and growth of the individual person … Just Peace cannot truly be said to exist without a resultant state of human flourishing … Sustainable development also requires the defense of the human rights and economic and property rights of the poor … and is therefore inseparable from legal and political development” (111).

Practice Norm 7: Work with emerging cooperative forces in the international system

We can rejoice in and seek to develop more of the social activism that through the social media has multiplied in the last couple of decades. But mostly, we should contribute to nongovernmental organizations that seek to alleviate the plight of the poor and shine a light on human rights violations. Some NGOs are faith-based, but many are not. Both types need to be supported.

Practice Norm 8: Strengthen the United Nations and international efforts for cooperation and human rights

Despite its flaws, the U.N. represents a key factor in fostering world peace. “Empirical data show that the more nations are engaged in supporting U.N. actions, the fewer wars they experience” (145).

Practice Norm 9: Reduce offensive weapons and the weapons trade

By lowering military budgets nations are able to spend more on sustainable development and in alleviating poverty. The arms trade has only increased the risk of conflict and war. We must find ways to build trust and cooperative conflict resolution.

Practice Norm 10: Encourage grassroots peacemaking groups and voluntary organizations

Individual peacemakers can only be effective as they build peacemaker communities and movements. “Grassroots organizations are inherently focused on transformation and do not easily become entrenched in cycles that perpetuate conflict and injustice” (195).

The crucial nexus of democracy and human rights

I want to conclude with the “Christian Reflection” by Matthew V. Johnson Sr., an African American pastor from Atlanta, an academic (PhD in philosophical theology from the University of Chicago Divinity School) and an activist (national director of Every Church a Peace Church). It’s easy to pick out the speck in our brother’s eye, Jesus said, and much harder to take out the log in our own. We can name any number of human rights abuses in other nations, but they are more difficult to see at home. Johnson quotes Martin Luther King Jr: “We have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights, an era where we are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society” (99).

Democracy in the United States, he then asserts, “excluded African Americans and other minorities.” Giving them their full human rights is a foundational democratic objective. Yet our track record so far is spotty at best: “The commitment to democratic values and ideals has ranged from very warm when in the interests of the ruling party, class, or race, to ice cold when it comes to subjects, servants, and slaves.” Western democracies in general leave many with a “hermeneutic of suspicion.” But that “healthy skepticism” does not undermine belief in democracy” (102).

The African American church, as a result, has developed over the years “an ethic of struggle,” focusing on the prophetic tradition of the Old Testament (the prophets calling for social justice) and on the eschatological passages in both testaments. God promises to make all things right in the world to come, and even before that he will come to judge the nations and all the oppressors and evildoers. One such passage also mentions peace: “And he shall judge among the nations, and shall rebuke many people: they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall no longer lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more” (Isaiah 2:4).

Racism in daily life has worsened for African Americans in the last couple of years. The high incidence of young blacks being shot by police is not going away, despite Black Lives Matter and other organizations. But though there’s been progress, sustainable economic development for this community is far behind what it is for whites, Asian Americans and Latinos. Look at this NPR article from yesterday on black homeownership (“In Baltimore, the gap between white and black home ownership persists”). That rate is about the same ratio as it is nationally: 43 percent for blacks, versus 72 percent for whites. But if you look at the graph there, you will see a dramatic decrease in rates for blacks after the “Great Recession” a decade ago. In fact, “the black homeownership rate today is just the same as it was in 1967.”

This is a failure in democracy and human rights, and as you can see, many of those norms for just peacemaking are interconnected and work not just internationally but nationally within the domestic fabric of each nation. Yet these are issues we can work on and successfully move forward, particularly in an interfaith mode. The third Muslim member of Congress was named last night (Rashida Tlaib replaced Rep. John Conyers who resigned last year) and the first Muslim woman. That’s on the political level, which of course is crucial for a democracy. But at the grassroots level, we should rejoice at all the interfaith organizations working in so many locations around this country. I know Peace Catalyst International very well, but there are others too, like the Abrahamic Alliance in the Bay Area pictured above. This should give us much hope.

Scott Pruitt, who until last week was President Trump’s Environmental Agency (EPA) Administrator, resigned amidst numerous ethics scandals. Yet he was ruthlessly effective in carrying his boss’s mandate to dismantle as many Obama-era regulations as possible. His deputy Andrew Wheeler, now the acting head of the EPA, will no doubt continue where he left off.

Of course, this was predictable. Pruitt, when he was Oklahoma’s attorney general, sued the EPA fourteen times. He had always been a staunch climate change denier. In an article that lists seven ways Scott Pruitt’s legacy will move ahead at the hands of his successor, the author argues that without the weight of scandals over him Wheeler will implement Trump’s deregulatory zeal even more effectively.

On top of that list was Pruitt’s lobbying for Trump to pull the US out of the Paris Accord and to dramatically downplay any connection between the rise of human-related greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and global warming. Never mind that the overwhelming majority of climate scientists contribute to and agree with the ongoing reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007). The IPCC was formed by two United Nation agencies in 1988 and its reports comb though all the most recent published studies in the field. The hundreds of scientists who contribute to this ongoing work all volunteer their services to the IPCC. They do so, believing in the urgency and crucial importance of their work as a way to reduce the suffering of future generations inhabiting this planet.

The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment came out in 2013 and the most complete summary of three Working Group contributions to this assessment was published in 2015 (“Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report,” available for download here). Perhaps this summary captures best the kind of tone exhibited by these ongoing reports (the Sixth Assessment is due to be published in September 2019):

“Anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions have increased since the pre-industrial era, driven largely by economic and population growth, and are now higher than ever. This has led to atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide that are unprecedented in at least the last 800,000 years. Their effects, together with those of other anthropogenic drivers, have been detected throughout the climate system and are extremely likely to have been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century.”

In this blog post I want to specifically examine the damage that sea level rise is already having on the United States eastern seaboard. But first, a look at new report on the accelerated melting of ice in Antarctica.

Polar ice runoff accelerating

We know that Arctic ice is melting faster and faster, if only because for the first time in human history ships can now cross that region in the summer months. But that ice is mostly sea ice, that is, icebergs or mammoth ice blocks floating in the sea. One of the big exceptions is Greenland, where the ice is melting fast, but not necessarily all going out to sea for now. Still, a recent study found that between 2011 and 2014, a trillion tons of ice has poured into the sea.

By contrast, Antarctica is a continent covered by ninety percent of the Earth’s ice, and were all those ice sheets to melt, the oceans would rise about 200 feet. Some of it is three miles thick, so it is not likely to see much of it melting for several hundred years. But the pace of melting is accelerating, and that speed has tripled in the last decade.

An article in Vox helps us to visualize the extent of this melting. An Olympic-size swimming pool contains 2,500 tons of water. Every second, Antarctica is losing three times that amount, which means that every forty hours, it looses one gigaton (or a billion tons) of ice. That is definitely more than the peak flow of Niagara Falls, and it is accelerating.

Eastern seaboard especially threatened

Because of the many factors involved, scientists cannot predict exactly to what extent the seas will rise in this century. The two direct causes are a) expansion of water as it warms; b) ice melt. But the main cause behind these is the rise of greenhouse gas emissions due to human activity. A NASA article (“Empirical Projections”) considers various studies and estimates that seas could rise anywhere between 0.2 meters and 2 meters. But if a midway position around one meter might seem conservative, even that would spell catastrophe for most of today’s human populations, which lives on the sea coasts.

As might be expected, this would affect poorer countries much more than wealthier ones. Miami and New Orleans will suffer from rising tides with more frequent and more powerful hurricanes, but the U.S. will no doubt find ways to lessen the impact of this rise on its population.

Not so for the Bay of Bengal, where almost one in four humans live. People from eastern India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia and Sumatra, all have to share in the pollution, which is enormous, and in the deadly consequences of dramatic sea rise. Lands in the various deltas is sinking, salt water is encroaching more and more on agricultural lands, and food production is threatened.

Still, the rate of sea level rise is projected to be higher on the U.S. east coast. An article published by the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies reports that “from 2011 to 2015, sea level rose up to 5 inches — an inch per year — in some locales from North Carolina to Florida.” This is much higher than most other coasts around the world. Why? It seems that three factors contribute to this: “a slowing Gulf Stream, shifts in a major North Atlantic weather pattern, and the effects of El Niño climate cycles.”

Miami already suffers from what is now termed “king tides,” or flooding from unusually high tides. Another study this year by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimated that by the end of the century this will happen every other day along the east coast. Then the Yale article adds this:

“Scientists have been steadily increasing their estimates of how much sea level overall will rise this century from melting glaciers and polar ice sheets. The current best estimates are in the range of 3 to 6 feet.”

Naturally, this would mean much higher sea level for the east coast and other places like the Gulf of Bengal where changing monsoon patterns have markedly heated and expanded the northern Indian Ocean. But in the Atlantic, you also have the Gulf Stream that is slowing down. This current of warm tropical water, about 100 to 200 miles from the coast “whisks water away from the eastern seaboard.” As recent research shows, its slowing down means that sea levels rise along the coast, and this is likely to increase as Arctic and Greenland ice dump huge quantities of fresh water into the North Atlantic.

Add to that the effect Pacific El Niño patterns have on the Jet Stream and wind patterns moving across the US to the Atlantic, but I have no room here to explain. Suffice it to say we have a convergence of factors that will wreak havoc in New York, Boston, and other eastern cities in the decades to come.

And then you have an increase in more devastating hurricanes, like Sandy in Oct./Nov. 2012. Here’s an article from May 2017 on that same Yale website, this time by Gilbert M. Gaul, who has won two Pulitzer Prizes and been a finalist four other times:

“Sea level rise played an important role in Sandy, with historic flooding from Delaware to the Battery in lower Manhattan. Upward of 100,000 people experienced flooding who otherwise would have been dry, researchers estimate. Most late season hurricanes veer out to sea by the time they reach the mid-Atlantic. Sandy took a hard left-hand turn, crashing ashore near Atlantic City and pushing a five-foot plume up the bays, into places water had never reached before.”

As you might imagine, insurance and real estate companies have taken notice. The federal insurance plan (National Flood Insurance Program, NFIP), even before Sandy was basically bankrupt. Zillow, a real estate firm, conducted a study that estimated that with a likely sea level rise of six feet two million homes worth about $900 billion along the eastern seaboard would literally be underwater by 2100. But again, we can figure that out and find a way to pay for it. A large percentage of those homes are secondary residences along the New Jersey shore. Cities like New York are already investing hundreds of millions of dollars in storm mitigation infrastructure.

Ethical and theological conclusion?

At the end of 2016, I posted a two-part blog on Pope Francis’ first encyclical, Laudate Si, which literally translates as “Praise be to you,” but with the subtitle, “On Care for Our Common Home.” There I did my best to unpack the pope’s “theology of planet care.”

By way of summary, by virtue of God’s creation God has delegated great responsibility to his human creatures to care for the earth he designed for them. They have plainly failed in many aspects of their divine calling, but it is not too late for common action:

“The climate is a common good, belonging to all and meant for all. At the global level, it is a complex system linked to many of the essential conditions for human life. A very solid scientific consensus indicates that we are presently witnessing a disturbing warming of the climatic system. In recent decades this warming has been accompanied by a constant rise in the sea level and, it would appear, by an increase of extreme weather events, even if a scientifically determinable cause cannot be assigned to each particular phenomenon. Humanity is called to recognize the need for changes of lifestyle, production and consumption, in order to combat this warming or at least the human causes which produce or aggravate it” (18-19).

The pope’s phrase “Humanity is called to recognize the need for changes” ties into his conviction that people of all faiths and of no faith – humanity in its entirety – must wake up to this crisis and work together. On this point, note that I posted a blog in 2012 on “Muslims Investing in our Planet” and I co-edited an issue on Islam and Ecology that year in the journal Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture and Ecology (see here). I have done less with Christians, but here is a short piece on evangelicals and ecology. For a statement by over 300 senior evangelical leaders on climate change, see here.

Certainly the three Abrahamic faiths emphasize the solidarity of the human race and the divine imperative to love God and love our neighbor, whoever and wherever on the planet he or she might be. It’s out of that imperative that I end with a note of urgency. What strikes me the most in what I learned for this piece is how various factors impinging on the climate are accelerating in their intensity and interactivity with one another. Less than a decade ago, scientists were talking about two or three feet of sea level rise as a worst-case scenario. Now six feet seems no longer an extreme prediction.

This only makes the Paris Accord all the more urgent – and the US pulling out of it all the more tragic, though it’s likely that states and large corporations will step in to realize similar goals. Many Pacific islands and nations will likely disappear before 2100. Droughts and flooding in various places will exact a staggering human toll. As people of faith in particular, we must not remain silent. Following Pope Francis, we must also lead the way in making “changes of lifestyle, production and consumption.” We must also pressure our politicians to sideline the use of fossil fuels and dramatically expand the use of clean energy as first steps.

The media was abuzz this last week with the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy and its resulting wrenching of children from their parents’ arms. He finally reversed course, but the damage internationally was done. UN high commissioner for human rights Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein put it this way , “The thought that any state would seek to deter parents by inflicting such abuse on children is unconscionable.” A couple of months ago, his office declared that this practice “amounts to arbitrary and unlawful interference in family life, and is a serious violation of the rights of the child.”

The United States, it turns out, is the only country in the world not to have ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which entered into force in 1990. In fact, it just pulled out of the Human Rights Council set up in 2006 over a number of complaints. But human rights discourse aside, you say, what difference should this make? Plainly, ripping children away from their families is a violation of human decency.

In this regard the history of human rights remains instructive (see also my two-part blog post on human rights). After two unimaginably violent and bloody world wars, momentum got under way for the creation of the United Nations and for a document that would clearly set some standards of human decency toward fellow human beings. The document that came to light in that process was the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

That same year the founding document of the United Nations, the UN Charter, had been signed by 50 countries on June 26, 1945 and ratified on October 24. It mandated for all member states “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.” But it was short on details.

Meanwhile, the UN Economic and Social Council established the 18-member Human Rights Commission (HRC), which in turn designated a Human Rights Drafting Committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt. The lead drafter was Canadian John Peters Humphrey, Director at the time of the Division of Human Rights within the United Nations Secretariat, but the lion’s share of ideas goes to three other influential members: the French jurist René Cassin, the Lebanese Charles Malik, and the Taiwanese scholar of Confucianism, P. C. Chang.

The committee met twice in as many years and the UDHR was adopted by the General Assembly on December 10, 1948, with 48 nations in favor, eight abstaining (including Saudi Arabia), and two failing to vote (Honduras and Yemen). Not one nation voted against it. Note that among the signatories you find eight Muslim-majority nations: Afghanistan, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Syria and Turkey.

Now I want to focus on the enormous contribution made in this process by Charles Malik. I will thereby highlight his role as a politician and especially as a theologian.

Charles Malik: global statesman

Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) hailed from a small north Lebanese village (Bitirram) in which his father served as medical doctor, and like many in his Greek Orthodox family and entourage, he went to a Protestant secondary boarding school, the Tripoli Boys School, one of over 40 such schools at the time run by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (BPFM). He then studied mathematics and physics at the American University of Beirut (also founded by the BPFM). But philosophy is what captured his attention the most, and he pursued a doctorate in philosophy at Harvard University under Alfred North Whitehead, including a year of study under Martin Heidegger in Germany (which he quickly left behind when the Third Reich was ominously beginning to take shape). He obtained his PhD in 1937.

Malik was an academic at heart, and only reluctantly did he dive into diplomacy and politics, first as Lebanon’s ambassador to the USA (1945-55), Lebanon’s Minister of Foreign Affairs (1956-58) and its Minister of National Education and Fine Arts (1956-57), and finally MP for the Koura region.

Malik’s greatest accomplishments, however, should be seen in his contribution to the United Nations. He was Lebanon’s delegate for the founding conference of the UN (San Francisco, 1945) and immediately wanted to contribute to the reinforcement of human rights. He managed to secure Lebanon’s place in the body most responsible for working on human rights, the UN Economic and Social Council, and this by thwarting Turkey’s bid to do so. This also meant that he became one of the 18 members of the newly formed Human Rights Commission (HRC). He chaired the third session of the UN General Assembly which presided over the passage of the UDHR, and it was largely because of his diplomatic skills that it passed unanimously with only eight abstentions.

Charles Malik’s son, Habib Malik, also a Harvard PhD, directs the Charles Malik Foundation, which in 2000 in collaboration with the Oxford Centre for Lebanese Studies published some of his father’s writings on human rights (The Challenge of Human Rights: Charles Malik and the Universal Declaration). Harvard Law professor and specialist in human rights law, Mary Ann Glendon (see her A World Make New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, New York: Random House, 2001) wrote the Introduction to that work, noting Malik’s extraordinary contribution:

“At one time or another, Malik held nearly all the major posts in the UN, including a rotating seat on the Security Council and the presidency of the General Assembly. During the period covered by most of the writings in this book, he served as rapporteur of the UN Human Rights Commission, which he later chaired” (1).

Before I focus on his particular contribution to the UDHR, allow me to comment on his subsequent academic career. Besides his record-breaking 51 honorary doctorates from all over the world, Malik taught in the USA at Harvard, the American University in Washington, DC, Dartmouth College, Notre Dame University in Indiana, and the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. He also taught in his home country as professor of philosophy at the University of Beirut (1962-76).

Charles Malik and Human Rights

First, his contributions as a philosopher: I’m following Mary Ann Weaver’s outline here. Already, Western nations were clashing with their communist counterparts on the issue of collectivism and the freedom of the individual. Malik urged all the delegates to look past their respective ideologies and focus on the human person. What is his nature? (this was before gender-inclusive language) Is he not than just an economic being, or one defined by his group, whether ethnic, religious, or political?

Malik steered the group away from Eleanor Roosevelt’s “Anglo-American-style individualism,” and by making an alliance with the two delegates from China and Latin America, “Malik saw man as uniquely valuable in himself, but as constituted in part by and through his relationships with others – his family, his community, his nation, and his God” (3). Thus he challenged both competing concepts, the oppressive state under the communists on the one hand; and the capitalist construction of society as atomistic individuals seeking their own economic self-interest.

Then too, Malik often insisted on the crucial distinction between society and state, and thus the importance of civil society: “Malik insisted on the political importance of the many associations and institutions of civil society that stand between the individual and the state – families, religious groups, professional associations, and so on. It is due in no small part to Malik’s vigilance that the declaration explicitly protects these mediating structures” (3).

Finally, the Preamble’s wording that human beings are “endowed with reason and conscience” is largely due to Malik’s insistence. This is no doubt an important philosophical concept, but it is also his way of making sure there was room for theological justification from a variety of religious traditions.

Second, his contributions as a diplomat. Glendon details the tremendous odds against securing the UN vote that would ensure the adoption of the UDHR. The June 1948 Berlin blockade all but guaranteed the collapse of the USSR-Western alliance. Procedure dictated that the Economic and Social Council had to approve the UDHR first. Unfortunately, it “was filled with hard-boiled, hard-nosed practitioners of realpolitik, and the declaration was expected to face strong opposition there” (4). Fortunately, it had elected a new president months earlier – Charles Malik himself! The document sailed through with flying colors, “to the astonishment of many,” Glendon adds.

The next seemingly insurmountable hurdle was obtaining the approval of the General Assembly’s Committee on Social, Economic and Cultural Affairs (aka, the Third Committee, composed of 58 members, one from each UN member state). Fortunately again, in the fall of 1948 when the final round of review convened, Charles Malik was elected chair by secret ballot. Yet here is a man who again and again in his diaries confesses his distaste for public life, and politics especially!

Writing about him, John Humphrey claimed in his memoirs that he was “one of the most independent people ever to sit on the Commission.” Independent or not, it took an inordinate amount of grit to get the job done – over 80 meetings all in all, with bitter arguments over every line. As the meetings spilled over into November, the level of anxiety was rising. The General Assembly would adjourn in December!

Malik had to balance pressure from the Soviet block that was deliberately extending discussions so as to kill the project, and from Mrs. Roosevelt and others who wanted to bring it to a vote as soon as possible. Coming from a small country himself, Malik calculated that the adoption could only come if every country could be brought on board. As Glendon puts it, “He was far-sighted enough to realize that a sense of ‘ownership’ on the part of many cultures would not only improve the declaration’s chances of adoption but, more importantly, would promote its lasting reception among the nations” (6).

Malik was relieved when, at the end of November, the Third Committee approved the declaration with no opposing votes and only seven abstentions. Historians give Malik most of the credit for achieving this victory.

Now the last great hurdle was passing the UDHR through the General Assembly. Any “no” vote would greatly compromise its future legitimacy. As mentioned earlier, in his December 9 speech he gave credit to the contributions of every major culture and nation, explaining that the UDHR had been “constructed on a firm international basis wherein no regional philosophy or way of life was permitted to prevail” (6). He then reviewed the document’s history and then declared that the UDHR would “serve as a potent critic of existing practice” and “help to transform reality.” At the same time he stressed that this was only the first step in harnessing the power of human rights to protect people.

To this Glendon adds, “How right he was! Though the Great Powers regarded the non-binding declaration as of little importance, its ‘merely’ moral force later eclipsed in importance the covenants that were adopted to implement its provisions” (7).

Charles Malik the ecumenist and theologian

If I succeeded in whetting your appetite for learning more about Charles Malik, your first step would be to consult this fascinating 2010 essay in the journal Biography (available if you can get access to a jstor.org account): (“Charles H. Malik and human rights: notes on a biography”). The author, Glenn Mitoma, is professor at the Human Rights Institute of the University of Connecticut, and this article was a prelude to his 2013 book, Human Rights and the Negotiation of American Power.

Mitoma argues in his essay that studying Malik’s work from the perspective of biography is particularly illuminating. Specifically, he stresses Malik’s Christian faith and how it underpinned both his objectives and philosophy on the Human Rights Commission and within the longer arc of his efforts as a Christian statesman.

This was possible because of Malik’s life-long loyalty to his Greek Orthodox upbringing while incorporating in a critical and discerning manner his American Protestant education. Quoting from Malik, Mitoma provides some useful information regarding his three years at the Tripoli Boys School (notice the many quotes by Malik):

“Malik ‘witnessed one of the profoundest and most lasting religious experiences’ of his life. The ‘short simple prayer’ at mealtimes, and the ‘disciplined, quiet, dignified’ march of students, two-by-two, to Sunday service at the Tripoli Protestant Church, helped him become aware, he said, of the ‘ultimate Christian religious realities.’ Malik expressed a deep admiration for and gratitude to the ‘God fearing men and women’ who staffed the school, and no doubt of greatest satisfaction to his audience of earnest and faithful humanitarians, spoke of the ‘true vision of Christ’ that had for the first time filled his heart.”

I already mentioned his son Habib Malik and the foundation bearing his father’s name. In his Foreword to an edited book in honor of his father’s centenary, Habib emphasizes two aspects of his father’s religious commitment: his intentional promotion of Christian unity beyond the three main traditions of the church (Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant) – the very definition of ecumenism; and his own devotion, and in particular, his “very special, life-long, intimate relationship with the Bible, which he read daily according to a rigorous schedule” (14). This emphasis makes sense in light of this book’s nature. It is built around the address that Malik gave at the 1980 inauguration of the Billy Graham Center on the Wheaton College campus in Wheaton, IL. This means that Billy Graham himself would have chosen Malik for this great honor. The address was simply entitled, “The Two Tasks,” and the book, The Two Tasks of the Christian Scholar: Redeeming the Soul, Redeeming the Mind.

I have no room here to comment on the book’s content, but let me simply make two remarks.

1. A vocation to Christian unity: Malik remained Greek Orthodox, but two of his brothers became Catholic priests (Jesuit and Dominican) and his mother’s family was mostly Protestant from the congregational tradition. In the World Council of Churches (WCC) context, he served as president of the World Council on Christian Education (1967-71). In an even more ecumenical institution, he served as vice president of the United Bible Societies (1966-71). As mentioned earlier, he taught in two Catholic universities over the years. As I peruse his list of twenty books or so, I see three theological books aside from many articles and speeches: Christ and Crisis (1962); God and Man in Contemporary Christian Thought (1970); he also edited a parallel book in 1967 relative to the Islamic tradition, both published by the American University of Beirut); finally, The Wonder of Being (1974).

2. His theological commitment to saving humanity’s soul and mind: clearly, if Billy Graham chose him for the inaugural address of his one and only venture into academia, he trusted Malik’s basic Christian commitment to evangelism – the mandate Jesus gave to his disciples to announce the Good News everywhere and make disciples of all nations (Mat. 28:19-20; Mark 16:15; Acts 1:8). But he also approved of his emphasis on “saving” the mind. And here Malik does not disappoint.

To sum up Malik’s speech, the great confusion the world is experiencing can be traced to a large extent to the cacophony of ideologies, which, despite their many differences, are all forms of self worship in the end – like “materialism and hedonism; naturalism and rationalism; relativism and Freudianism; a great deal of cynicism and nihilism; indifferentism and atheism … (the list goes on).” His message is simple, and it is appropriately addressed to evangelicals (jokingly, Wheaton is often called “the evangelical Mecca”). He doesn’t mince his words: “the great danger besetting American Evangelical Christianity is the danger of anti-intellectualism” (63).

He also says, “Christ being the light of the world, his light must be brought to bear on the problem of the formation of the mind. The investigation will have to be accomplished with the utmost discretion and humility, and it can only be carried out by men of prayer and faith … We are dealing here with a thoroughgoing critique, from the point of view of Jesus Christ, of Western Civilization as to its highest contemporary values” (63-64). Then further on we read, “If it is the will of the Holy Ghost [Spirit] that we attend to the soul, certainly it is not his will that we neglect the mind. No civilization can endure with its mind being as confused and disordered as ours is today” (64).

Though he had no time to mention this in his address, Malik might well have brought up the issue of human rights. And that is where I particularly resonate with his work and life. Christians must reflect deeply on the implications of God’s creation of humankind on the one hand. What does human dignity mean from that angle? This concern we share with people of all faiths and no faith. And on the other, what does the cross of Jesus mean for the redemption of individuals and nations, for the power of forgiveness and healing in a broken and fractured world?

Both Bible and Qur’an teach God’s imperative for economic justice. Everyone has a God-given right to the bounty God has bestowed on humankind. And we are duty-bound to share it.

More on that below, but first, the piece that got me thinking about this in the first place: a short review by Felix Salmon of Chris Hughes’ book that came out in February 2018 (Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn).

Chris Hughes was Mark Zuckerberg’s roommate at Harvard and co-founded Facebook with him. After three years he left with several hundred million dollars to his name. “I have too much money,” he says. Salmon explains,

“Hughes is acutely aware of how unfair this is. ‘Most Americans cannot find $400 in the case of an emergency,’ he writes, ‘yet I was able to make half a billion dollars for three years of work.’ He’s also aware that the flip side of people like himself having too much money is that tens of millions of Americans have too little. Over 40 million Americans live below the poverty line, including one in five children under the age of 6.”

Remember the Occupy Wall Street protest movement that started in September 2011? It was set against the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans monopolizing the nation’s wealth to the detriment of the rest of the population. “We are the 99 percent!” went the slogan.

Hughes’ solution is for one percenters like himself to collectively pay a monthly grant of $500 to all working Americans making under $50,000, including those caring for small children or the elderly at home. Critics point out that this excludes the poorest of the poor and the disabled who will continue to depend on the miserly grants already in place. So in practice this would only help 42 out of 120 million American households.

Yet Hughes didn’t pull this idea of using cash grants to solve poverty out of a rabbit’s hat. As a young philanthropist, he made two exploratory trips to Kenya. First, he traveled with the renowned American economist Jeffrey Sachs and studied his Millennium Villages Project. Sach’s premise is that all the infrastructure (including good education and healthcare) needs to be set up first and then people will thrive and wealth will multiply for the benefit of all. The second trip was with economist Michael Faye, cofounder of GiveDirectly, “a nonprofit that has a much simpler strategy of supplying cash grants to people living on less than a dollar a day.” That seemed to him to be a more efficient and effective strategy to reduce poverty. So Hughes founded his own nonprofit, The Economic Security Project. The Amazon page for his book describes it as “a network of policymakers, academics, and technologists working to end poverty and rebuild the middle class through a guaranteed income.”